Improving Value

Addressing Health Disparities: A Spectrum of Approaches

As the documented evidence of pervasive health disparities in our system has continued to grow since the release of the 1985 Heckler Report, much of health disparities research has pivoted to the question of how do we reduce disparities and move towards an equitable health system?

There are plenty of places to start. The Hub's State and Local Health Equity Policy Checklists identify areas for improvement by evaluating states' performance on 39 health equity-related policies across six domains.

In addition, a collection of evidence-based strategies to address health disparities that can be pursued at the state level are listed below:

Data to Support Disparities Work

For states to tackle racial and ethnic health disparities in a meaningful way, there needs to be adequate data to understand local conditions. States can support data collection efforts as follows:

- Pursue administrative or legislative policies that require state level data collection to further disaggregate racial and ethnic demographic categories.1

- Support dissemination and sharing of existing data among stakeholders. Encourage data sharing agreements when possible to formalize and structurally support dissemination

- Promote Community-Based Participatory Research, especially among academic institutions in diverse communities, to increase racial and ethnic minority group participation in clinical trials.2

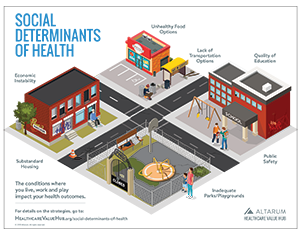

Address Social Determinants of Disparities

To make a meaningful difference in addressing health disparities, interventions must begin outside of the medical sector and tackle the social determinants of health. When possible, act community wide and address root causes by improving education, housing, food insecurity and other social determinants of health. There are also many interventions that work directly at the patient level and address individual social determinants of health.

- Advocate for policies that promote or require social determinants of health screening in clinical settings, especially in pediatric care.3 In addition to screening for social determinants, including social service workers in clinical care settings can help address disparities. Models of care that integrate social service and/or caseworkers into medical settings have demonstrated significant impact in improving patient health outcomes, as well as often reducing health care spending. Examples of successful models include screening for malnutrition, and connections to housing support, meal delivery programs and social service referral programs.4

- Promote community level prevention efforts for risk factors and disease specific screenings for diseases, especially for chronic conditions that disproportionately impact minority communities, such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

- Intervene early in prenatal care through home visiting programs provided by nurses, social workers, paraprofessionals or community health workers/promotoras. Not only have home visiting programs been effective at improving infant and maternal health,5 they also improve child development and promote effective parenting.6

- Improve nutrition and reduce food insecurity with the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and innovative farmer’s market incentive programs like Double Up Food Bucks.7

- Support the development and implementation of Accountable Communities of Health (ACH) models to bring together community-based and clinical organizations to achieve better population health outcomes.8

Address Disparities in Access

Scan for the dominant barriers for accessing health care, things like being uninsured/underinsured, transportation issues, provider shortages, etc. and tailor policy solutions to address those barriers. For example:

- Advocate for efforts to expand Medicaid and other policy solutions to address the coverage gap

- Increase access to primary and preventive care with school-based health centers (SBHC) and programs

- SBHC have made a documented improvement in school districts serving minority communities. Over 70 percent of the students in schools with operating SBHC are students of color. These health centers improve access to care, have high levels of patient satisfaction, and have improved education and health outcomes, including among conditions that disproportionately affect minority communities such as asthma and obesity.9

- Promote telehealth to increase providers reach in underserved areas. Telehealth has proven to be an effective strategic in addressing prenatal care in rural communities, including managing at-risk pregnancies and reducing the number of very-low-birth-weight births in these communities.10 Electronic consultation and telemedicine have also successfully increased patient access to specialists for managing numerous chronic conditions including diabetes, autism and substance use disorders.11

- Support Community Health Worker (CHW) initiatives and training programs. CHWs have not only demonstrated impact on community health through successful preventive and risk screenings, but these interventions have documented cost-effectiveness.12 Community Health Workers have also successfully improved maintenance of costly chronic conditions such as diabetes among underserved populations.13

- Monitor any licensing initiatives for community health workers in your state and require answers to how these policies will affect access to care.

- Examine how Nurse Practitioners can help address provider shortages in underserved communities and support state level policies that reduce unnecessary limitations in their scope of practice.

Addressing Disparities in Treatment

Health disparities persist even after controlling for disparities in access and social determinants. Improved treatment and patient outcomes for populations of color goes beyond patient perception and satisfaction data. Research has shown that minority physicians are more likely to care for socioeconomically disadvantaged and ethnic minority patients.14 Additionally, studies have demonstrated that unconscious bias may lead to physicians providing different treatments and prescriptions for the same condition, especially when it comes to reported experiences of pain for people of color.15

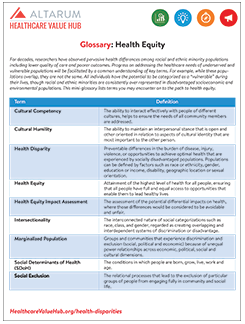

Strategies to address include growing a diverse health care workforce and providing training on cultural humility and implicit bias for existing and future health care provider workforces. But it takes time for these approaches to pay dividends. Specific policies include:

- Support mentorship and pipeline programs to recruit and retain minority students in clinical professions.16

- Encourage state educational institutions to establish post baccalaureate programs that promote success in medicine for minority students whose parents did not attend college.17

- Look at the languages and backgrounds of the populations served and how it aligns with the current workforce. Research has found a link between racial and ethnic similarities of patients and physicians and the quality of doctor patient communication.18 Patients have also documented that providers of their same race and ethnic background have been more engaged and participatory in treatment.19

- Provide or promote cultural competency and/or cultural humility trainings. While the evidence around the effectiveness of these trainings are limited, preliminary reviews show a link to increased patient satisfaction and provider knowledge.20

Support Local Efforts

If the above interventions are out of reach or there is insufficient data to get started, support state and local meetings on health equity and health disparities. In many communities, this work has already begun and existing bodies are working to achieve health equity. In resources limited environments, often all that can be offered is organizational support or participation, but this contribution is an important one. To achieve the goal of an equitable health system, robust community partnerships are vital in the effort to eliminate health disparities.

Notes:

1. Rubin, Victor, et al., Counting a Diverse Nation: Disaggregating Data on Race and Ethnicity to Advance a Culture of Health, PolicyLink (August 2018).

2. De Las Nueces, Denise, et al., "A Systematic Review of Community-Based Participatory Research to Enhance Clinical Trials in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups," Health Services Research, Vol. 47, No. 3, Part 2 (June 2012).

3. Cernansky, Rachel, "Screening for Social Problems," U.S. News (Feb. 6, 2019).

4. Castrucci, Brian, and John Auerbach, "Meeting Individual Social Needs Falls Short of Addressing Social Determinants of Health," Health Affairs Blog (Jan. 16, 2019).

5. Wells, Natalie, et al., "The Impact of Nurse Case Management Home Visitation on Birth Outcomes in African-American Women," Journal of the National Medical Association, Vol. 100, No. 5 (May 2008).

6. Barlow, Allison, et al., "Paraprofessional-Delivered Home-Visiting Intervention for American Indian Teen Mothers and Children: 3-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Controlled Trial," American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 172, No. 2 (February 2015).

7. Savoie-Roskos, Mateja, et al., "Reducing Food Insecurity and Improving Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Farmers' Market Incentive Program Participants," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Jan. 1, 2016).

8. Spencer, Anna, and Bianca Freda, Advancing State Innovation Model Goals through Accountable Communities for Health, Center for Health Care Strategies (October 2016).

9. Keeton, Victoria, et al., "School-Based Health Centers in an Era of Health Care Reform: Building on History," Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, Vol. 42, No. 6 (July 2012).

10. Marcin, James P., et al., "Addressing Health Disparities in Rural Communities Using Telehealth," Pediatric Research, Vol. 79 (2016).

11. Research Brief No. 19: Improving Healthcare Value in Rural America, Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (October 2017).

12. Landers, Stewart, and Mira Levinson, "Mounting Evidence of the Effectiveness and Versatility of Community Health Workers," American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 106, No. 4 (April 2016).

13. Spencer, Michael S., et al., "Effectiveness of a Community Health Worker Intervention Among African American and Latino Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial," American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 101, No. 12 (December 2011).

14. Green, Alexander R., et al., "Implicit Bias Among Physicians and Its Prediction of Thrombolysis Decisions for Black and While Patients," Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 9 (September 2007).

15. Wilson, Yolanda, "Dying While Black: Perpetual Gaps Exist in Health Care for African-Americans," The Conversation (Feb. 5, 2019).

16. Mason, Bonnie S., et al., "Pipeline Program Recruits and Retains Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Procdure Based Specialties: A Brief Report," American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 213, No. 4 (April 2017).

17. Grumbach, Kevin, and Eric Chen, "Effectiveness of University of California Postbaccalaureate Premedical Programs in Increasing Medical School Matriculation for Minority and Disadvantaged Students," JAMA, Vol. 296, No. 9 (September 2006).

18. Powe, Neil R., and Lisa A. Cooper, Disparities in Patient Experiences, Health Care Processes, and Outcomes: The Role of Patient-Provider Racial, Ethnic, and Language Concordance, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y (July 1, 2004).

19. Cooper, Lisa A., Patient-Centered Communication, Ratings of Care, and Concordance of Patient and Physician Race, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (Dec. 1, 2003).

20. Govere, Linda, and Ephraim M. Govere, "How Effective is Cultural Competence Training of Healthcare Providers on Improving Patient Satisfaction of Minority Groups? A Systematic Review of Literature," Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, Vol. 13, No. 6 (Oct. 25, 2016).