Low vs High Value Care

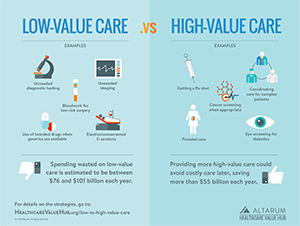

One reason for excessive spending in the healthcare system is that we still provide low-value care when it has been proven to be marginally clinically beneficial but costs a lot. Shockingly, this excess is accompanied by the under-provision of high-value care. Achieving a high-value, patient-centered, equitable healthcare system requires rebalancing this equation.

|

Low-value care are healthcare services that have little or no clinical benefit.1 In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated the U.S. wasted $340 billion on unnecessary healthcare services and inefficiently delivered services—that would be $501 billion in 2018 dollars.2 This low-value care can harm patients directly by putting them at risk from unnecessary procedures and testing, or by diverting resources away from high-value care. Strategies that could reduce the provision of this care include increasing comparative effectiveness research, provider education and non-financial incentives, establishing widely acknowledged goals for reductions, provider payment reform, patient shared decision making and medical harm reporting. Choosing Wisely is a campaign to encourage conversations between physicians and patients to reduce the use of low-value care. However, there is a lack of consensus on how to incorporate clinical nuance, patient preference and priorities, and cost-benefit tradeoffs into provider and consumer discussion to reduce low-value care in healthcare.3 See this page for more on low-value care. |

|

|

High-Value care. Ideally all clinical care would have a net clinical benefit but certain forms of care—like preventive care—can reliably and predictably provide substantial individual and population health benefits. For example, the National Commission on Prevention Priorities released a list in 2016 of 28 high-value services with strong evidence of effectiveness, population-wide health impact and cost-effectiveness.4 Highest ranked services included immunizing children, counseling to prevent tobacco initiation among youth, and tobacco-use screening and brief intervention to encourage cessation among adults; alcohol misuse screening with brief intervention, discussing aspirin use with high-risk adults, colorectal cancer screening, cervical cancer screening, chlamydia and gonorrhea screening, cholesterol screening, hypertension screening, obesity screening and more. |

This high-value, cost-effective preventive care is often underutilized for certain groups, including individuals with multiple chronic diseases, low-income and minority populations, and patients undergoing care transitions.5 For example, one study found only one-third of the potential health and economic benefits of tobacco counseling are being realized.6 Moreover, researchers have demonstrated patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes often do not receive proven and effective treatments such as drug therapies or self-management services to help them more effectively manage their conditions. This is true for insured, uninsured, and under-insured Americans.7

By increasing the use of high-value, cost-effective care we can achieve better outcomes, reduce health inequities and possibly save money—more than $55 billion each year according to one estimate.8

Strategies to increase the provision of high-value care are include aligning provider payment and contracting to support high-value care, real-time clinical decision support systems, and public reporting of progress.

1. Grovner, Lori, What to Know About Low Value Care and the High Value of Eye Examination, Eye Health Net (November 2017). https://eyehealthnet.com/2017/11/22/what-to-know-about-low-value-care-and-the-high-value-of-eye-examination/

2. Institute of Medicine, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America, The National Academies Press (2013). Also see the Hub’s infographic on healthcare waste.

3. Beaudin-Seiler, Beth et. al., Reducing Low-Value Care. Health Affairs Blog (September 2016). https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160920.056666/full/#two

4. National Commission on Prevention Priorities Releases new Preventive Services Rankings, American Academy of Family Physicians (January 2017). https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-01/aaof-nco010417.php

5. https://www.brookings.edu/research/improving-quality-and-value-in-the-u-s-health-care-system/

6. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2017-01-national-commission-priorities.html

7. https://www.brookings.edu/research/improving-quality-and-value-in-the-u-s-health-care-system/

8. Satcher, David. Preventive Interventions: An Immediate Priority. Annals of Family Medicine. (January 2017). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5217838/