Bundled Payments: What Does the Evidence Say?

Bundled payments are an alternative payment model that pays providers (doctors, hospitals, etc.) for bundles of services rather than for each individual service they provide. The exact makeup of services that fall within each bundle—called an episode of care—can vary by condition (e.g., pneumonia) or procedure (e.g., knee replacement). Generally, each episode includes the full range of services that a person receives throughout their course of care.

The goal of bundled payments is to incentivize the providers involved in a patient’s course of treatment to collectively deliver high quality care at a lower cost. Theoretically, this is accomplished by paying the providers a fixed sum for each episode of care, regardless of the number of services they provide. Groups of providers who deliver care for less than the set amount (while meeting quality standards) can share in the savings, incentivizing them to make cost-effective care decisions.1

“An episode of care involves the entire care continuum for a single condition or medical event, such as joint replacement or labor and delivery, during a fixed period. It includes all acute and post-acute care delivered by hospitals, physicians, skilled nursing facilities, and other providers participating in a care pathway.” – NEJM Catalyst 2

Payment Methodology

Provider payments under bundled payment models can be prospective or (more commonly) retrospective. Prospective models pay providers a negotiated single payment for a clinical episode in lieu of traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payments. Retrospective models pay providers the usual FFS payments, and the total FFS payment for the clinical episode is reconciled against a predetermined target price after a given period of time.3 Providers that deliver care for less than the set amount receive a reconciliation payment, while providers that exceed the target price owe a reconciliation payment to the payer. Both types of reconciliation payments are adjusted based on quality performance.

Federal Bundled Payment Models

Bundled payments target specialists, who have traditionally been less likely than primary care physicians to participate in value-based payment models.4 The vast majority of experimentation, to date, has occurred within the Medicare program.

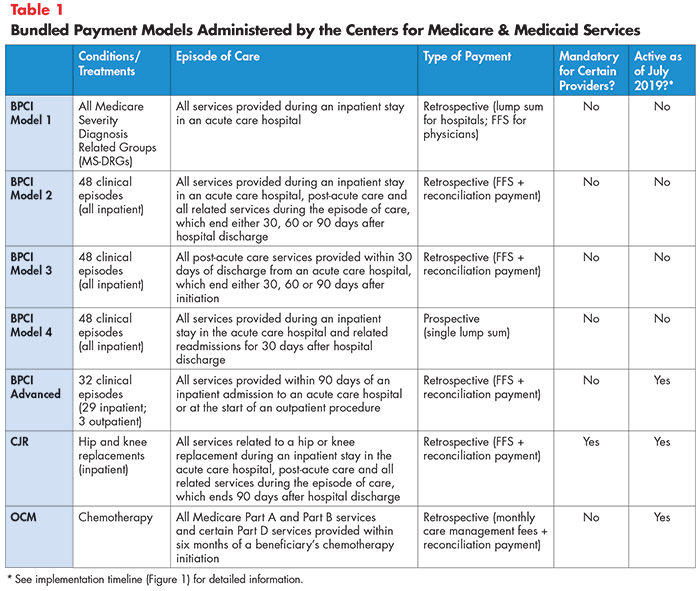

As of 2019, bundled payment models in Medicare include:

- Bundled Payments for Care Improvement—Models 1-4

- Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement

- Oncology Care Model

- Bundled Payment for Care Improvement—Advanced

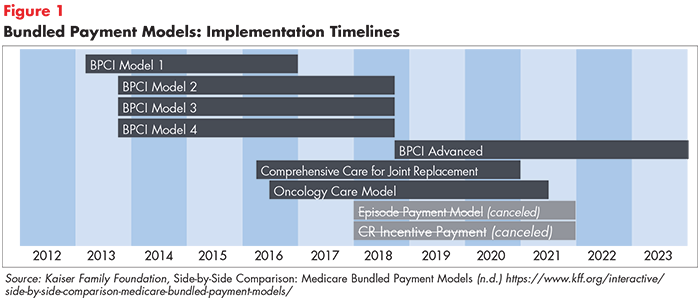

Two additional experiments—Episode Payment Models and Cardiac Rehabilitation Incentive Payments—were scheduled to begin in 2018 but were canceled by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2017. Descriptions of active models and their implementation timelines are provided in Table 1 and Figure 1.

What Does the Evidence Say?

Reliably assessing bundled payment models’ effectiveness is difficult due to the initiatives’ voluntary natures. All models except Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) allow providers to withdraw from the program if they start to lose money, which skews evaluation results. Additionally, it is likely that organizations that choose to participate are inherently different from those who do not (and serve as the control group to which participants are compared).5 Nevertheless, best available evidence suggests that some models are more effective than others at reducing costs without negatively affecting quality of care.6

Bundled Payment for Care Improvement

Evaluations of Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI), which bundles provider payments for up to 48 medical conditions and procedures, have shown mixed results. Current evidence suggests that the model is more effective when applied to surgical procedures, rather than medical conditions.

The vast majority of BPCI data comes from BPCI Model 2—the largest of the four models tested. Participating providers most commonly opted to receive bundled payments for major joint replacement of the lower extremity, commonly known as hip and knee replacements.7

Studies show that BPCI participation reduced hospitals’ per-episode costs of care without affecting mortality, readmissions or related emergency department visits.8,9 Additionally, patient-reported outcomes, like satisfaction and pain level, were either unaffected or improved.10

One study found that approximately half of hospitals’ savings stemmed from changes in the provision of post-acute care. Hospital executives cited reductions in skilled nursing facility referrals, greater use of home care supports and better coordination with skilled nursing facilities through electronic health record integration and employing care coordinators as strategies for success.11 Ultimately, reward payments to providers exceeded per-episode savings—therefore, BPCI did not generate savings to the Medicare program.12

Early evidence on bundled payments for medical conditions (as opposed to procedures) is less promising. A 2018 study of five common conditions—congestive heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis and acute myocardial infarction (a.k.a., heart attack)—under BPCI found no significant changes in cost or quality between participating hospitals and a control group.13

Potential reasons for the discrepancy in results for medical conditions and procedures include:

- An inability to use inpatient admission to trigger a condition-specific episode of care (medical conditions begin before a person is hospitalized, whereas surgical procedures do not).

- Care for medical conditions may take longer to redesign than care for surgical procedures.

- Reducing the use of post-acute care without negatively affecting quality may be more difficult when treating medical conditions than after surgical procedures.14

At the time of this writing, little research has been conducted to confirm or disprove these theories.

Lessons learned from BPCI Models 2-4 have contributed to the “new and improved” BPCI Advanced, which began in October 2018. This model will test inpatient and, for the first time, outpatient episodes of care. Also for the first time, it will hold participants accountable for performing on two standardized quality measures across all episodes—readmissions and advanced care plans. Previously, participants could propose and seek Medicare approval for their own quality measures.15

The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is optimistic that BPCI Advanced will better achieve savings to the Medicare program without negatively affecting quality, although the model has yet to be evaluated.16 Moreover, because many participating providers have opted for condition-specific bundles, the BPCI Advanced will likely contribute to our knowledge of successful approaches for non-procedural bundles.17,18

Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement

Hip and knee replacements are prime procedures for bundled payments because the episodes of care are fairly routine with wide variation in cost under fee-for-service arrangements. Additionally, health outcomes are easy to measure because the patient population is generally healthy, with few complex health conditions that muddy results.

Studies of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model, which bundles payments for hip and knee replacements, have documented reductions in per-episode spending with no effect on healthcare quality, although payment reductions were smaller than those observed under BPCI. Like BPCI, reward payments to providers ultimately negated savings to the Medicare program.19,20 Another study found that only half (48%) of participating hospitals produced savings, and there was wide variation in savings among hospitals in the same market. Hospitals that achieved savings tended to be larger, with a higher volume of procedures and were more likely to be a nonprofit or teaching hospital and be integrated with post-acute care facilities.21

Unlike other models (BPCI and OCM), CJR is mandatory for providers operating in certain metropolitan service areas. This distinction could explain the difference in per-episode savings from knee and hip replacement episodes under BPCI versus those under CJR, as BPCI had a greater percentage of participants with characteristics linked to success. These findings demonstrate that the results of one bundled payment model may not be generalizable to other models and that certain hospitals may face additional barriers to success that discourage participation in voluntary programs.

Smaller incentives in the first year of CJR may also account for the lesser savings compared to BPCI.22 Future studies should monitor the effect of incentive size on per-episode savings as the incentives increase over time.

Oncology Care Model

The Oncology Care Model (OCM), which bundles payments for services related to chemotherapy, is unique in that it includes commercial payers (in addition to Medicare) to more strongly incentivize care transformation.23 As of 2019, relatively little is known about OCM’s impact on costs. CMMI estimates of total Medicare spending (using data from the first six months of the program) suggest that there is an 85 percent chance that OCM is achieving “some level of savings.”24 However, these savings are unlikely to offset incentive payments made to participating providers. OCM’s impact on quality is similarly unknown. Future research will clarify these effects as more data becomes available.25

State-Level Bundled Payment Initiatives

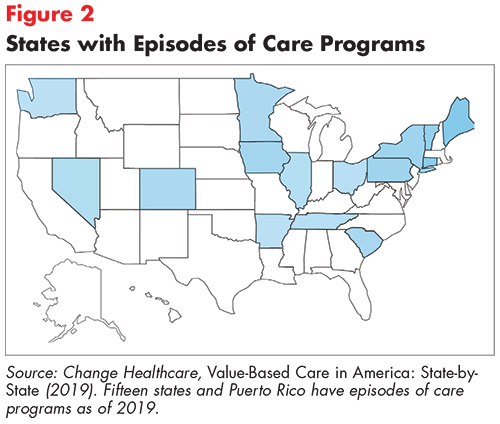

Fifteen states and Puerto Rico have implemented episodes of care programs as of 2019 (see Figure 2).26 Tennessee’s Episodes of Care Initiative is innovative in that it bundles payments across public and private payers and has achieved largely positive results. Arkansas’ Episode-based Care Delivery model is also praised for bundling payments across payers, but its results have been mixed.

Tennessee’s Episodes of Care Initiative

Tennessee implemented episode of care payments with four major commercial payers, all three TennCare (Medicaid) Managed Care Organizations and CoverKids (the Children’s Health Insurance Program) in 2015.27 Initial episodes focused on three service bundles—total joint (i.e. hip and knee) replacement, hospitalization for acute asthma exacerbation and pregnancy—with 45 more bundles introduced between the initial set and July 2019.28 Commercial sector organizations participate in a rewards-only program, while Medicaid Managed Care Organizations also face penalties for poor performance.29 The state’s employee benefit plans transitioned to mandatory participation in 2017.

Payment methodology: Tennessee’s initiative retrospectively bundles payments for providers. Providers are initially paid on a fee-for-service basis and payments are reconciled against spending benchmarks at the end of a given performance period (typically lasting one year). Those whose average spending falls below the “commendable” benchmark while meeting quality standards share in the savings, while providers whose average spending falls above the “acceptable” benchmark must reimburse the payer for part of the overage. Reimbursement for providers with acceptable but not commendable average spending levels remains the same.30

Results: Tennessee’s episodes of care model decreased spending by $10.8 million (for three bundles) in 2015, $14.5 million (for eight bundles) in 2016 and $28.6 million (for 19 bundles) in 2017. Only two bundles—acute percutaneous coronary intervention and bariatric surgery (both introduced in 2017)—failed to produce savings. The vast majority of quality metrics remained the same or improved.31

Overall, financial rewards paid to providers exceeded financial penalties in each of the three years evaluated. However, penalties exceeded rewards for over half of the bundles implemented in 2017, indicating that some providers have struggled to meet spending benchmarks for these procedures/conditions.32

Arkansas’ Episode-based Care Delivery

Arkansas implemented bundled payments in 2012 through a public-private partnership between two insurance companies and the state’s Medicaid program.33 The initiative began when Arkansas Medicaid, Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BCBS) and QualChoice of Arkansas partnered to create the Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative (AHCPI).34 AHCPI aims to incentivize providers to deliver higher quality, less costly care using two primary strategies—a total cost of care patient-centered medical home program and an episodes of care model.35

Payment methodology: Providers participating in AHCPI’s episodes of care model are paid on a fee-for-service basis for up to 11 distinct episodes of care.36 FFS payments are risk-adjusted to ensure that providers are not unfairly penalized for treating less healthy (i.e. higher-risk) patients.37

As in Tennessee, participating providers’ average per episode costs are compared to pre-determined spending benchmarks at the end of each performance period (lasting one year). Providers whose average spending falls below the “commendable” benchmark while meeting quality standards share in the savings, while providers whose average spending falls above the “acceptable” benchmark must reimburse the payer for part of the overage. Reimbursement for providers with acceptable but not commendable average spending levels remains the same.38

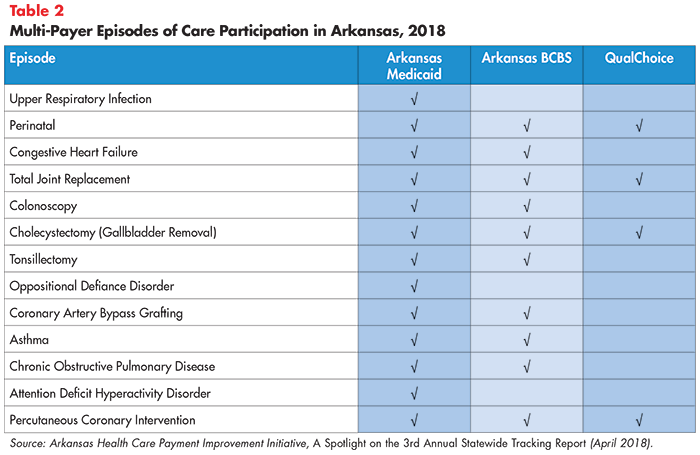

Results: Results from Arkansas’ initiative are difficult to generalize given the substantial variation in episode participation across payers. As of 2018, Arkansas Medicaid offered bundles for 13 conditions/procedures, while Arkansas BCBS and QualChoice of Arkansas offered bundles for 10 and 4 episodes, respectively (see Table 2).39

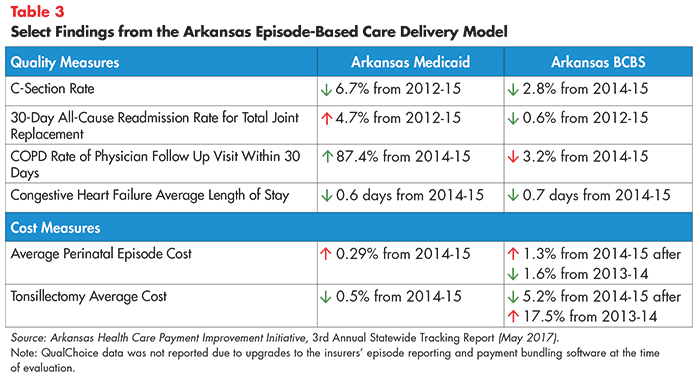

Although bundles implemented across payers were identical in design, independently established performance thresholds for rewards and penalties prevents a reliable comparison of results. Additionally, performance data for 2015 (the most recent year from which data is available) was reported only for Arkansas Medicaid and Arkansas BCBS; QualChoice data was not reported due to upgrades to the insurers’ episode reporting and payment bundling software at the time of evaluation.40

Available information suggests that Arkansas’ model’s impact on quality and costs has been mixed (see Table 3). Nonetheless, impressive improvements have been documented for specific measures reported by specific payers. Examples include an 87 percent increase in the rate of COPD 30-day follow up visits with a physician from 2014-2015 (reported by Medicaid) and a 67 percent decrease in the rate of acute asthma exacerbation within 30 days after an initial discharge from 2014-2016 (reported by BCBS).41

Elements of Successful Programs

While the evidence on bundled payments is still emerging, existing analyses have shed light on certain elements that help ensure providers’ success. As mentioned previously, bundled payments generally work well for routine procedures with wide variation in cost under fee-for-service payments. They are also better suited for relatively healthy patients with no more than one complex health condition.

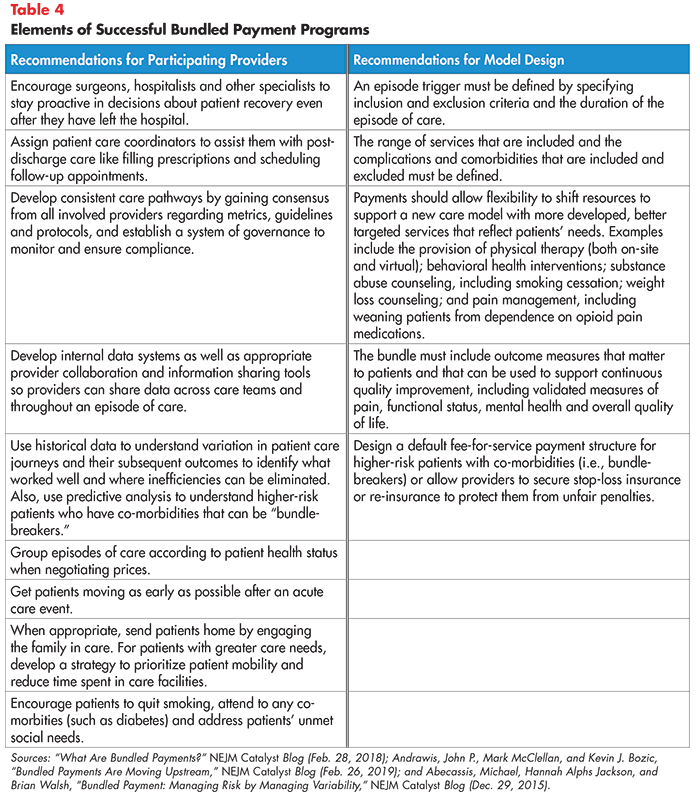

Table 4 outlines nine lessons learned from the early experiences of providers and four factors that contribute to effective bundled payment model design.42

Lingering Challenges

Meeting cost and quality benchmarks under bundled payment models is harder for providers treating patients with co-morbidities or health-related social needs beyond their control.43 In the case of patients with two or more chronic health conditions, for example, it may be difficult to identify which condition caused an unplanned hospital readmission and determine which provider should be held accountable. Furthermore, the voluntary nature of these programs makes it likely that providers will withdraw if they feel they are at risk of being unfairly penalized.

Conclusion

Best available evidence suggests that bundled payments for some surgical procedures control costs without negatively affecting quality. The payment approach may be particularly well suited for procedures that are non-urgent and predictable with wide variation in cost, despite consistent quality. Nevertheless, it is increasingly apparent that the use of bundled payments alone will not lower costs, improve quality and eliminate all unnecessary care.

More research is needed to assess bundled payments’ long-term impact, understand why they have been less successful for medical conditions and identify specific conditions that are a good fit for bundled payment models. The Dell Medical School at The University of Texas-Austin’s Musculoskeletal Institute, for example, has had some success bundling services related to degenerative joint disease.44

Future studies should also compare bundled payments to other alternative payment models to determine which best incentivizes providers to meet cost and quality goals. For example, comparative research is lacking with regards to bundled payments and global budgets, which prospectively pay providers a lump sum annually to address the needs of a given population.45 Issues related to provider readiness—such as an insufficient understanding of how to support providers that do not exhibit characteristics linked to success under bundled payment models—must also be addressed. Given these unknowns and the recent implementation of the “new and improved” BPCI Advanced, bundled payments will likely remain an important part of the alternative payment model toolbox for several years to come.

Notes

1. RevCycle Intelligence, Understanding the Basics of Bundled Payments in Healthcare: How do bundled payments fit into the growing value-based reimbursement ecosystem? (accessed on June 10, 2019).

2. “What Are Bundled Payments?” NEJM Catalyst Blog (Feb. 28, 2018).

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Advanced: Request for Applications, Baltimore, MD (April 18, 2019).

4. Blumenthal, David, and David Squires, The Promise and Pitfalls of Bundled Payments, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (Sept. 7, 2016).

5. Lown Institute, Are Bundled Payments Working? Yes and No, Brookline, Mass. (Sept. 6, 2018).

6. Kaiser Family Foundation’s interactive, easy-to-use table summarizes findings to-date. See: https://www.kff.org/interactive/side-by-side-comparison-medicare-bundled-payment-models/

7. Dummit, Laura, et al., CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2-4: Year 5 Evaluation & Monitoring Annual Report, Lewin Group, Falls Church, V.A. (October 2018).

8. Glickman, Aaron, Claire Dinh and Amol S. Navathe, The Current State of Evidence on Bundled Payments, University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, Philadelphia, P.A. (Oct. 8, 2018).

9. A 2019 study conducted by the Lewin Group assessed BPCI Model 2’s impact on Medicare beneficiaries with one or more of the following “vulnerabilities:” dementia, dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and/or recently received institutional care. Researchers found that BPCI participation did not affect quality of care (in 12 types of clinical episodes) for these vulnerable populations. See: Maughan, Brandon C., et al., “Medicare’s Bundled Payments For Care Improvement Initiative Maintained Quality Of Care For Vulnerable Patients,” Health Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 4 (April 2019).

10. Glickman, Dinh and Navathe (Oct. 8, 2018).

11. Ibid.

12. Dummit, et al. (Oct. 2018).

13. Lown Institute (Sept. 6, 2018). See also: Joynt Maddox, Karen E., et al., “Evaluation of Medicare’s Bundled Payments Initiative for Medical Conditions,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 379, No. 3 (July 19, 2018).

14. Glickman, Dinh and Navathe (Oct. 8, 2018).

15. Researchers acknowledge the importance of aligning quality measures across participating providers, although the value of these specific measures has been called into question. See: Navathe, Amol S., Ezekiel J. Emanuel and Joshua M. Liao, “Policy Trends That May Drive Different Care Redesign For Procedural Versus Nonprocedural Bundles,” Health Affairs Blog (April 11, 2019).

16. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative, Models 2 – 4: Evaluation Years 1 through 3 (through December 31, 2016), Baltimore, M.D. (n.d.)

17. Popular condition-specific bundles include congestive heart failure, stroke, cardiac arrhythmia, sepsis and urinary tract infection.

18. Dalzell, Michael D., "Why Bundled Payments are Poised to Take Off," Managed Care (Nov. 25, 2018).

19. Glickman, Dinh and Navathe (Oct. 8, 2018).

20. Finkelstein, Amy, et al., The Impact of Bundled Payments on Medicare Spending, Utilization, and Quality in the United States, Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, Cambridge, Mass. (Sept. 4, 2018).

21. Glickman, Dinh and Navathe (Oct. 8, 2018).

22. Finkelstein, et al. (Sept. 4, 2018).

23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Oncology Care Model, Baltimore, M.D. (n.d.).

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, Evaluation of the Oncology Care Model: Performance Period One, Baltimore, M.D. (n.d.)

25. A 2019 blog in Health Affairs explains critical aspects for future OCM evaluations: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190212.101448/full/

26. To download, visit: https://inspire.changehealthcare.com/stateVBRstudy See also: https://www.changehealthcare.com/docs/default-source/press-release/change_healthcare_value-based_care_in_america_state-by-state_infographic.pdf?sfvrsn=9217b232_2

27. Tenncare, Model Test Project Narrative (n.d.) https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/ProjectNarrativeTNSIMgrant.pdf

28. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/ProgramDescription.pdf. See also: https://mailchi.mp/70d386fa1a5b/episodes-of-care-pausing-future-episode-design-annual-episodes-design-feedback-session-presentation-slides?e=72de562267

29. Change Healthcare, Value-Based Care in America: State-by-State (2019).

30. Tennessee Medical Association, Retrospective Episodes of Care, Nashville, T.N. (n.d.).

31. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/TennCareEpisodes2017Results.pdf

32. In 2017, provider penalties exceeded rewards for the following bundles: total joint replacement, cholecystectomy, colonoscopy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), urinary tract infection (both inpatient and outpatient), congestive heart failure (CHF), oppositional defiance disorder (ODD), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and bariatric surgery. See: Ibid.

33. Bailit, Burns and Houy (May 2013).

34. Participants have since expanded to include Centene/Ambetter, the Arkansas State Employee and Public School Employee Plan, Walmart, HealthSCOPE and Arkansas Superior Select. See: Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, A Spotlight on the 3rd Annual Statewide Tracking Report (April 2018).

35. Ibid.

36. As of 2019, episode-based payments apply to the following four conditions—upper respiratory infection (URI), congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma—and seven procedures—perinatal care, hip and knee replacement, colonoscopy, cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal), tonsillectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Episode payments for two behavioral health conditions—attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiance disorder (ODD)—ceased in 2018. Arkansas Medicaid and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arkansas are considering developing additional episodes, including: appendectomy, uncomplicated pediatric pneumonia, hysterectomy and urinary tract infection when an ER visit is involved. See: Ibid.

37. Hussey, Peter S., M. Susan Ridgley and Meredith B. Rosenthal, “The PROMETHEUS Bundled Payment Experiment: Slow Start Shows Problems in Implementing New Payment Models,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 11 (November 2011).

38. Ibid.

39. Payers selected the episodes for implementation that met their covered population needs and corporate interests; thus, not every episode was implemented by each payer. See: Arkansas Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, 3rd Annual Statewide Tracking Report (May 2017).

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. The Lewin Group’s Public Toolkit also identifies “ingredients” for success. See: Lewin Group, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: Public Toolkit, Falls Church, V.A. (Feb. 2019).

43. RevCycle Intelligence (accessed on June 10, 2019).

44. Early results include a double-digit improvement in patients’ functional status at the first follow-up visit and a 25 percent decrease in the utilization of elective surgical procedures among the population receiving care. See: NEJM Catalyst Blog (Feb. 26, 2019).

45. From Q&A discussion at AcademyHealth’s 2019 Annual Research Meeting.