Community Health Needs Assessments: Elevating Consumer Voices, Increasing Accountability and Facilitating Collaboration

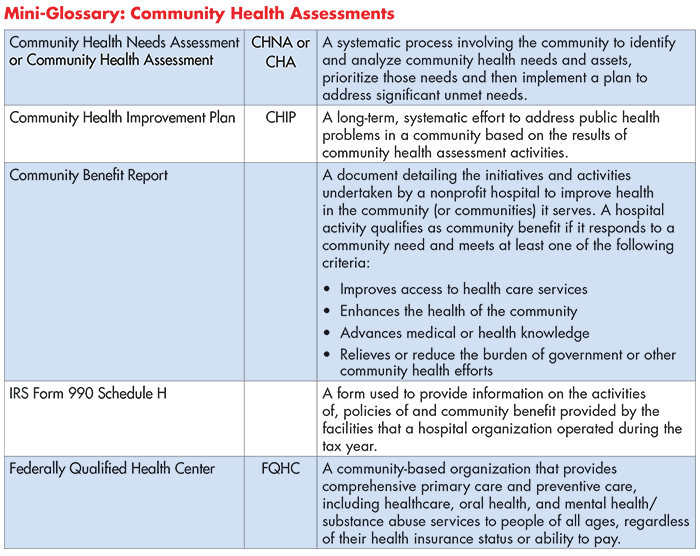

A community health needs assessment (CHNA) is a report that identifies the healthcare and health-related (food, housing, etc.) needs of a community’s residents.The goal of a CHNA is to systematically assess a community’s unmet needs in order to develop strategies to address them.

Three types of entities have a formal, federal obligation to conduct community health needs assessments:

- Nonprofit hospitals,

- Public Health Departments and

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)

This report describes how community health needs assessment requirements can be leveraged to improve health in a community.

Entities that Conduct Assessments

Nonprofit Hospitals

Nonprofit hospitals benefit from significant federal tax breaks. In return, the federal government requires them to provide a sufficient level of "community benefit" to justify the tax relief.

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), nonprofit hospitals primarily satisfied their community benefit requirement by providing free or reduced-price “charity care” to un- or under-insured patients who were unable to pay for the services they received. The ACA strengthened requirements for nonprofit hospitals to demonstrate community benefit—chief among them, requiring the production of CHNAs to assess people’s health-related needs beyond hospital walls and within the communities in which they live, work and play. The ACA also requires nonprofit hospitals to produce an accompanying Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP) outlining the hospital’s strategy to address the newly identified needs and to report progress toward meeting the goals identified in the previous CHIP.

CHNAs and CHIPs must be conducted every three years, in addition to an annual report detailing the types of "community benefits" the hospital provides.1 While the assessment process can be performed in partnership with other hospitals, each facility must produce its own CHNA report and make the document publicly available.2 This public reporting requirement does not apply to the CHIP or the annual community benefit report.

By statute, the CHNAs must take into account input from “persons who represent the broad interests of the community served by the hospital facility, including those with special knowledge of or expertise in public health.”3 This obligation provides an opportunity for community members, organizations, advocates and public health agencies to engage with hospital leadership and influence the direction the hospital takes in addressing community health needs.

Public Health Departments

In 2011, the Public Health Accreditation Board added “community health assessments” (CHAs) to its accreditation requirements for health departments. Specifically, the departments are required to “conduct and disseminate assessments focused on population health status and public health issues facing the community” every five years. Responsibilities include:4

- Participate in or lead a collaborative process resulting in a CHA;

- Collect and maintain reliable, comparable, and valid data that provide information on conditions of public health importance and on the health status of the population;

- Analyze public health data to identify trends in health problems, environmental public health hazards and social and economic factors that affect the public’s health; and

- Provide and use the results of health data analysis to develop recommendations regarding public health policy, processes, programs or interventions.

Similar to their hospital counterparts, public health departments seeking accreditation also must produce a community health improvement plan. When these documents are prepared by state public health departments they are referred to as State Health Needs Assessments and State Health Improvement Plans.

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)

A FQHC is a community-based organization that provides comprehensive primary care and preventive care, including healthcare, oral health and mental health/substance abuse services to people of all ages, regardless of their health insurance status or ability to pay. As such, FQHCs are a critical component of the healthcare safety net.

In order to establish appropriate local health service programs, FQHC’s must assess the unmet need for health services in the center’s catchment, or proposed catchment, area based on the population served.5 The FQHC must complete or update a needs assessment at least once every three years and must utilize the most recently available data for the service area and, if applicable, for special populations. Furthermore, the assessment must document the following critical components:6

- Factors associated with access to care and healthcare utilization, such as geography, transportation, occupation, transience, unemployment, income level or educational attainment;

- Significant causes of morbidity and mortality, in addition to associated health disparities; and

- Any other unique needs or characteristics that impact health status or access to/utilization of primary care (like social factors, physical environment, cultural/ethnic considerations, language barriers or housing status).

Leveraging Needs Assessments Requirements

It is widely reported that 80 percent of people’s health outcomes are affected by factors outside of the healthcare system (such as access to nutritious food, safe housing, education, income security and other socio-economic factors).7 Yet, “research shows that hospitals spend the majority of their community benefit resources on clinical care—including charity care and Medicaid shortfalls—rather than on community health improvement or community-building activities that can address the social determinants of health.”8 In some cases, inadvertent failure to meaningfully engage a diversity of residents in the assessment process has contributed to the misunderstanding or inaccurate prioritization of community needs. Other institutions have been accused of simply “checking the box” when it comes to CHNAs, by satisfying minimum federal requirements but doing little else to support community members’ health and well-being beyond the walls of their establishments.

While regulatory or statutory compliance may motivate these institutions to conduct the assessments, advocates and community members have the opportunity to strengthen the assessments’ quality and hold reporting entities accountable for developing effective, evidence-based strategies to address high-priority local health needs (including health inequities).9 In order to do this work effectively, they must first understand the challenges to producing high quality assessments and opportunities for improvement.

Challenges

Vague Guidance on Community Engagement

Current federal guidance governing CHNAs is problematically vague, leaving a great deal open to interpretation. For instance, nonprofit hospitals must solicit input from “persons who represent the broad interests of the community,” however, IRS rules specify only two stakeholder groups that hospitals are required to engage.10 As a result, some assessments include perspectives from a rich diversity of community stakeholders, while others incorporate input from a select few.

Additionally, the IRS permits, but does not require, nonprofit hospitals to assess community members’ needs outside of the traditional healthcare system, potentially allowing important social determinants of health to remain unaddressed. Amending the guidance to require hospitals to include stakeholders like social support providers would ensure that health-related social needs are more accurately assessed.

Finally, ambiguity over the term “community” leads some hospitals to narrowly focus assessments on their immediate service areas, rather than the broader environments in which their patients live and work. Too narrow, or too broad, of scope may distort results, undermining the effectiveness of the assessments.

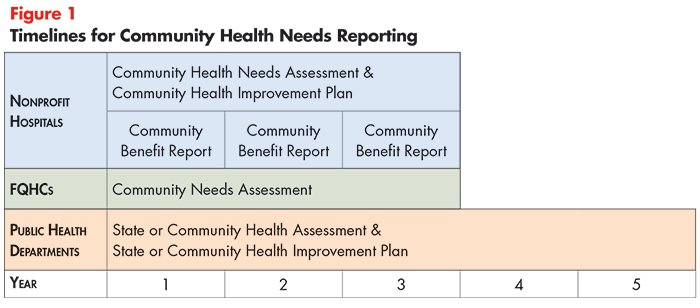

Mis-Matched Timelines

In many communities, nonprofit hospitals, public health departments and FQHCs work in silos, each producing an assessment unique to their organization or agency. Stakeholders have lamented that lack of coordination wastes resources and results in repetitive, yet incomplete, assessments.11

Lack of coordination is due, in part, to different schedules for completion. As previously stated, public health departments are required to conduct assessments every five years, while nonprofit hospitals and FQHCs must produce reports every three years (see Figure 1). It is also important to note that the assessment schedules of nonprofit hospitals (even those operating in the same community) may vary due to guidance that required hospitals’ inaugural CHNA to be conducted in their first taxable year after March 23, 2010 (and repeated at 3-year intervals thereafter).12

Lack of Resources and Organizing Expertise

Some hospitals have been accused of neglecting important stakeholders like public health departments and community-based organizations in the production of their CHNAs. It is important to recognize, however, that even well-meaning organizations may struggle to meet this expectation, as employees working in the departments charged with producing the reports often lack experience bringing together stakeholders in pursuit of a common community goal. What’s more, some departments lack the resources to devote employees to this work, meaning that the responsibility may be added to the workload of already busy employees or fall on the shoulders of an inexperienced student intern. Lack of a dedicated workforce with the skillset necessary to perform this work impedes these organizations’ ability to succeed.

Opportunities

CHNAs can be a powerful tool to create healthier communities if reporting entities are supplied strong guidance, sufficient resources and solicit input from a diversity of stakeholders. State-level community benefit laws can hold organizations more accountable, while collaborative assessments can strengthen organizational capacity. Advocates can support the process by gathering community member input to aid in the assessment and influence priorities.

State Requirements for Nonprofits

Currently, states vary in the community benefit obligation they impose on nonprofit hospitals in exchange for exemption from state and local taxes. Some states go beyond the federal requirements by requiring hospitals to specifically report how their community benefit investments address the social determinants of health or meet the needs of underserved populations.13 Others establish a minimum amount of money that hospitals must spend on community benefits.14

States can also clarify expectations for “meaningful community engagement,” and expand community benefit requirements to include other nonprofit organizations that influence health. For example, New Hampshire requires nonprofit behavioral health providers, retirement communities and nursing homes to produce CHNAs and community benefit plans, in addition to the state’s nonprofit hospitals.15

Collaborative Assessments

City-or county-wide community health needs assessments produced by collaboratives of community stakeholders(for example, Accountable Communities for Health) offer a promising way to comprehensively assess residents’ needs. Strong examples include Live Well San Diego’s city-wide assessment16 and Columbia Gorge Health Council’s regional assessment spanning seven counties across Oregon and Washington (see Spotlight below).17

|

Spotlight: Columbia Gorge’s Comprehensive Community Health Needs Assessment The Columbia Gorge Regional Community Health Assessment is a comprehensive, regional CHNA produced by a collaborative of hospitals, clinics, public health agencies and community-based organizations operating in the Columbia Gorge Region. In 2012, 39 organizations participated in the collaborative’s first assessment, which culminated in a list of shared priorities from which to base regional health improvement efforts. In 2016, Columbia Gorge won the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s prestigious Culture of Health Prize for its innovative programs, developed in response to the CHNA.18 |

Currently, there is not much information that is publicly available on city- or county-wide CHNAs, including research on the potential benefits (compared to multiple CHNAs produced by organizations in the same community) or inventories of existing efforts. A fundamental building block appears to be the existence of a collaborative body in which numerous community organizations can come together in pursuit of a common goal. Oregon’s law establishing Coordinated Care Organizations (similar to Accountable Care Organizations)—and requiring them to conduct periodic needs assessments—is one example of how states can catalyze multi-stakeholder partnerships to assess (and subsequently address) barriers to community members’ health and well-being. Amending federal guidance to create a single assessment timeline would also facilitate collaboration by making needs assessments a priority for multiple organizations/agencies in a community at the same time.

Role for Advocates

Community engagement is an essential ingredient to a valuable CHNA and the establishment of priorities that are responsive to residents’ wants and needs. By making sure that important and diverse voices are represented at the table, advocates can ensure that the needs identified in CHNAs accurately reflect those of the community at-large, with a particular focus on populations experiencing health disparities. They can also advocate for coordinated assessments across hospitals, public health departments and FQHCs; provide best-practice strategies that reporting entities can implement as a part of their improvement plans; and ensure that they are held accountable for meeting the goals identified in their improvement plans (additional opportunities for participation are listed in the box below).

|

Opportunities for Advocates to Participate in the CHNA Process

|

Conclusion

Community health needs assessments, when conducted properly, are important tools for detecting, and subsequently addressing, health-related community needs. While some organizations have exceeded expectations, many have a long way to go. Advocates can hold hospitals, public health departments and FQHCs accountable by seeking opportunities to participate in the process, as well as advocating for policy changes that clarify expectations and make it easier for organizations to work together.

These assessments also present an opportunity for healthcare organizations to play a meaningful role in broader efforts to address social determinants of health.

Notes

1. U.S. National Library of Medicine, Community Benefit/Community Health Needs Assessment, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hsrinfo/community_benefit.html (accessed March 25, 2016).

2. Collaborating hospitals may produce a shared CHNA if they (1) serve the same community and (2) include all of the information in the joint report that would have been required in two individual reports. See: https://www.irs.gov/charities-nonprofits/community-health-needs-assessment-for-charitable-hospital-organizations-section-501r3

3. Ibid.

4. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Community-Based Health Needs Assessment Activities: Opportunities for Collaboration Between Public Health Departments and Rural Hospitals, Arlington, V.A. (2017). http://www.astho.org//uploadedFiles/Programs/Access/Primary_Care/Scan%20of%20Community-Based%20Health%20Needs%20Assessment%20Activities.pdf

5. U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration, Health Center Program Compliance Manual Chapter 3: Needs Assessment, Rockville, M.D. (August 2018). https://bphc.hrsa.gov/programrequirements/compliancemanual/chapter-3.html

6. Ibid.

7. Alberti, Philip, “Community Health Needs Assessments: Filling Data Gaps for Population Health Research and Management,” eGEMs, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Jan. 21, 2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4371524/

8. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, Measures & Data Sources, http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/what-and-why-we-rank (accessed on March 19, 2019).

9. Clary, Amy, States Work to Hold Hospitals Accountable for Community Benefits Spending, National Academy for State Health Policy Blog (May 8, 2018). https://nashp.org/states-work-to-hold-hospitals-accountable-for-community-benefits-spending/

10. Hospitals are explicitly required to consult at least one public health department and members of medically underserved, low-income and minority populations in the community served during the assessment process. In practice, the quality of these partnerships vary dramatically depending on the organizations/agencies/groups involved. See: https://www.irs.gov/charities-nonprofits/community-health-needs-assessment-for-charitable-hospital-organizations-section-501r3

11. Hunt, Amanda, Consumer-Focused Health System Transformation: What are the Policy Priorities?, Healthcare Value Hub (March 2019).

13. Clary (2018).

14. Ibid.

15. Academy for State Health Policy, Hospital Community Benefits Comparison Table for Six New England States, (n.d.). https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Hospital-community-benefits-chart-final-5_3_2018.pdf. See also: The Hilltop Institute, Community Benefit State Law Profiles, Baltimore, M.D. (n.d.). https://hilltopinstitute.org/our-work/hospital-community-benefit/hospital-community-benefit-state-law-profiles/

16. County of San Diego, Live Well San Diego Community Health Assessment (Oct. 22, 2014). http://www.livewellsd.org/content/dam/livewell/community-action/CHA_Final-10-22-14.pdf

17. Columbia Gorge Health Council, Columbia Gorge Regional Community Health Assessment 2016 (June 2017). http://cghealthcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Columbia-Gorge-Community-Health-Assessment-Full-Document-June-2017.pdf

18. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Columbia Gorge Region, Oregon and Washington: 2016 Culture of Health Prize Winner, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/features/culture-of-health-prize/2016-winner-oregon-washington.html (accessed on Feb. 3, 2019).