Hospital Rate Setting: Successful in Maryland but Challenging to Replicate

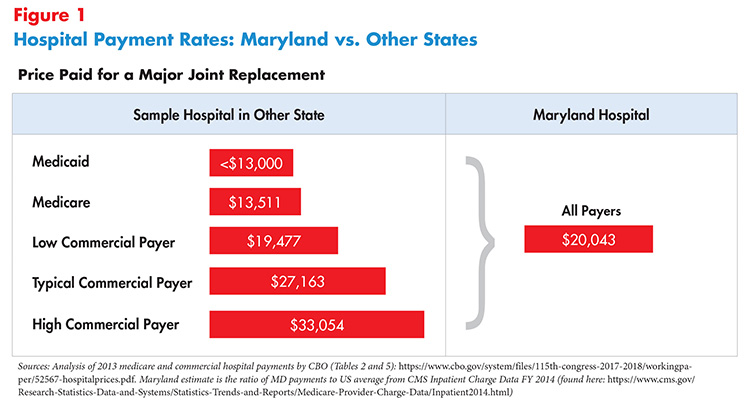

In most states, hospitals negotiate payment rates with each payer. Payers can include private health insurance plans, self-insured employer plans, and uninsured individuals, and may also include public payers like Medicaid and Medicare.1,2

Hospital rate setting is a system in which an authority, usually a state agency, establishes uniform rates for hospital services for multiple payers. When every payer in the state participates—as is the case in Maryland—it is referred to as all-payer hospital rate setting.

This paper updates Hub Research Brief No. 1 (March 2015; first updated August 2017) with results from Maryland’s most recent Medicare waiver, and the state’s progress towards the Triple Aim: Improving the individual experience of care, improving population health and reducing per capita costs.

What Value Problems Does Rate Setting Address?

Hospital care (inpatient and outpatient) accounts for about one-third of national healthcare spending.3 Moreover, hospital spending is expected to increase by 5.7 percent per year, on average, during 2020-2027—far exceeding the general rate of inflation.4 Annual increases in hospital spending have been identified as a major driver of medical spending, and even a modest decrease can mean annual savings of billions of dollars.5 Moreover, in many areas of the county hospitals have achieved enormous market power, both by acquiring other hospitals but also by acquiring physician practices. Variations in market power have resulted in tremendous variation in the prices charges by private payers for similar hospital services, sometimes far exceeding the cost to provide services.6 The prevalence of price discrimination can leave smaller payers and the uninsured paying much higher prices for hospital services. Such a system also adds to administrative waste and inequitable health outcomes.7

A hospital rate setting system can potentially contain costs, increase equity and reduce administrative waste by establishing payment levels and controlling the rate of growth of those payment levels over time. In addition, a rate setting system can provide a platform for aligned approaches to improve the quality and equity of care. When quality incentives are built into the payment rates of every payer, they apply to the full population of patients, rather than just an individual insurer's population, increasing the incentive to deliver care more efficiently and improve quality. Because spending flows and performance metrics are publicly debated, these systems can provide better price and quality transparency to the public.

All-payer systems, such as Maryland's, require a federal waiver in order for the state's rate setting agency to replace Medicare's payment rules with its own. While the form of this waiver has evolved over time, it generally requires that the state's payment rules not exceed the amount that Medicare would have spent under its regular payment rules for hospitals.

What Does the Evidence Say?

A study of Maryland's system has found that rate setting can be successful in controlling the rate of hospital cost increases.8 However, success depends on the way in which rate setting is implemented, as well as regulators’ ability to enforce the rates and impose penalties for noncompliance.

The evolution of Maryland's system over decades provides a wealth of evidence and lessons learned, as described below.9,10

Maryland Model (1971-2013): Formulation and Evolution of the All-Payer Rate Setting System

Like many other states, Maryland established its hospital rate setting system in the 1970s. The Maryland Hospital Association initially proposed rate regulation as a means of financing the growing levels of hospital uncompensated care. In response, the state established the Health Services Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), a state agency with broad powers of hospital rate setting and public disclosure. With a 1977 Medicare waiver, Maryland added Medicare rates to their system, creating a true “all-payer” approach, with all public and private payers paying on the same basis.

During these early decades using the all-payer rate system, Maryland has effectively moderated per admission spending growth and improved the financial stability of the state’s hospitals.11 Average hospital cost per admission in Maryland went from 26 percent greater than the national average in 1976 to 2 percent lower in 2007.12 Further, the system helped create a more equitable spread of the costs of uncompensated care and helped eliminate cost-shifting among payers.13

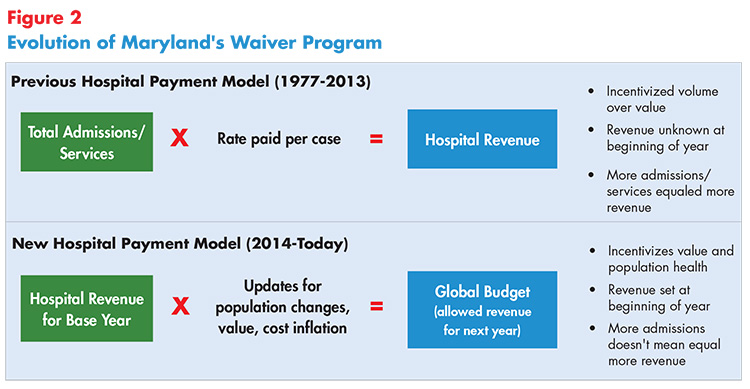

However, while the system effectively reduced per-admission costs, Maryland faced challenges with the original model. Hospital admissions in Maryland increased at a rate of 2.7 percent from 2001 to 2007 compared to the national average of 1 percent, indicating that the approach created perverse incentives for high volume.14

Total Patient Revenue System (TPR) Pilot Program (2008-2010; 2010-2013)

To address the increase in hospital admissions, in 2008 Maryland piloted a global budget system for hospitals as an incentive to reduce unnecessary admissions and readmissions. The idea was that fixed, predictable revenues tied to performance measures would eliminate incentive for unnecessary admissions and give hospitals the flexibility to invest in care improvements. Participating hospitals received a fixed global budget covering all outpatient and inpatient services, based on hospitals’ revenue from the previous year (see Figure 2). Prior-year revenue was then adjusted by an estimate of underlying cost inflation, demographic changes in the hospitals’ service areas and relative performance on specific quality measures.15

Ten rural community hospitals participated in the three-year pilot called the Total Patient Revenue System (TPR) program. Overall, the TPR hospitals successfully reduced the number of admissions and readmissions, as well as emergency department visits. For example, between 2010 and 2014, a western Maryland hospital reduced inpatient admissions by 32 percent and reduced readmissions by 42 percent.16 A 2019 study comparing TPR hospitals to non-TPR Maryland hospitals found that emergency department admission rates, ambulatory surgery visit rates, and outpatient visits and service rates fell by 12 percent, 45 percent, and 40 percent, respectively.17

But the findings are mixed. A second 2019 study found little impact on inpatient admissions, although it similarly concluded that outpatient and non-emergency department (ED) visits decreased.18 This study compared population-level utilization between ZIP code areas assigned to a TPR hospital service area or a non-TPR hospital service area. Three years after implementation, researchers found no significant changes in inpatient admissions, either overall or discretionary. In addition, researchers found a 15 percent decrease in non-emergency department outpatient visits (including outpatient clinic visits and outpatient surgeries.

Global Budget Model (2014-2018): Making Progress Towards the Triple Aim

Based on learnings from the global budgeting TPR pilot, in 2014, Maryland launched a new initiative to modernize the rate setting system. Under a new five-year Medicare waiver from CMS, the rate setting system evolved to be based on containing total, annual per capita hospital cost growth rather than payment per admission or per episode.

The waiver required that Maryland transition at least 80 percent of hospital revenue to “population-based payment methods,” like the TPR hospitals. In addition, Maryland was required to meet the following goals:19

- limit the growth in annual all-payer per capita hospital spending to less than 3.58 percent;

- reduce Medicare hospital spending by $330 million over the five-year period;

- limit annual per-beneficiary Medicare hospital cost growth so it does not exceed the national average;

- reduce the 30-day, unadjusted, all-cause, all-site readmission rate for Medicare patients to the national average; and

- reduce potentially preventable complications by 30 percent during the waiver period.

Early results were mixed. One study that compared changes in utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in Maryland with out-of-state control groups in the first two years had inconsistent results.20 Researchers found no clear evidence that hospitals met their budgets by reducing hospital utilization or enhancing primary care beyond changes that would have been expected without a global budget system.

However, by the fourth year of the waiver, the program was performing well against the program benchmarks. A 2019 evaluation shows that Maryland had already met or exceeded most waiver requirements by year three.21

Medicare Spending and Utilization

- The Gobal Budget Model reduced both total expenditures and total hospital expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries without shifting costs to other parts of the healthcare system. With a five-year cost-saving goal of $330 million, Maryland saw cumulative Medicare savings in hospital expenditures of $796 million through 2019.22

- The reductions in Medicare hospital expenditures were driven by reduced spending for outpatient hospital services. Though Medicare's spending for ED visits and observations stays combined did decline during the first three years of the all-payer model, the combined number of ED visits and observation stays increased. However, researchers posit that this increase may reflect hospitals' success in reducing admissions of Medicare beneficiaries seen in the ED.

- Inpatient admissions decreased but patient severity and the payment per admission increased, effectively canceling out any impact on total inpatient spending for Medicare beneficiaries. The state experienced a 7.2 percent reduction in admissions and a 6.7 percent decline in ambulatory care sensitive admissions among Medicare patients.23 While the implied per admission reimbursement under Maryland's “all-payer” approach is higher than what Medicare pays in other states, lower utilization savings meant net hospital savings overall for the Medicare program.24

- Medicare readmission rates decreased, but they also decreased in the comparison group. An earlier evaluation found the state reduced the gap in Medicare readmissions compared to the national average by 116 percent between 2013 and 2017. As of 2017, this was .19 percent lower than the national readmission rate.25

Commercial Payer Spending and Utilization

Maryland patients with commercial plans experienced 6.1 percent slower growth in hospital expenditures relative to a comparison group; however, total spending did not decrease due to offsetting higher use of professional services.26

The combined rate of ED visits and observation stays declined for commercial plan members, which researchers believe could be due to hospitals' attempts to move ED use to other settings.27

Other data show hospitals have expanded efforts to help patients transition home or to post-acute settings after discharge. They are using case managers in EDs to connect patients to primary care and other resources, and proactively treating chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and pulmonary disease.28 Furthermore, by the third year of this program, hospitals were increasing their focus on “high-risk, high-cost patients,” who frequently have complex social and medical needs that may require higher use of hospital services, such as individuals with severe mental illnesses or substance use disorders.29 Outcomes improved for beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions and beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid relative to other Medicare beneficiaries during the all-payer model period.30 Also during this time, hospitals reduced potentially preventable complications, such as Clostridium Difficile infections and decubitus ulcers, by 48 percent, sailing past the 5-year target.31

On the other hand, coordination of care with community providers, as measured by follow-up visits after hospital discharge, did not improve.32 Lack of provider engagement and provider shortages were cited as barriers to improving care coordination.

Maryland Model (2019-2027): Implementing the Total Cost of Care Model

Encouraged by the success of the global budgeting model, Maryland submitted a progression plan to CMS, termed the Total Cost of Care (TCOC) Model. Under the expansion, the all-payer model applies to some doctors' visits and other outpatient services, such as long-term care. Community healthcare providers are able to choose whether they want to participate in the model. The TCOC model provides tools and incentives for clinicians, hospitals, nonhospital facilities, and specialists to coordinate with each other and provide parient-centered, preventative, and timely care, while ensuring their financial stability.33

While Maryland's regulatory authority is limited to hospitals and Medicaid services, the progression plan calls for engaging physicians and other clinicians in voluntary efforts to redesign care. In addition, the plan places a renewed emphasis on population health improvement, particularly for complex, high-need patients.

The 8-year TCOC waiver is the first model in which CMS has held a state fully at risk for the total cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries—the financial targets are more than $1 billion in Medicare savings by 2023.34 The Total Cost of Care model includes three programs:

- Hospital Payment Program. Similar to earlier waivers, the program provides each hospital with a population-based payment amount to cover all hospital services provided throughout the year, creating financial incentives to provide value-based care and reduce unnecessary hospitalization and readmissions.

- Care Redesign Program. The program prioritizes partnership and collaboration between nonhospital healthcare providers and hospitals. Hospitals may make incentive payments to outside providers and collaborators who perform care redesign activities intended to improve quality of care, but only after the hospital has met certain savings benchmarks.

- Maryland Primary Care Program. The program incentivizes primary care providers to offer advanced primary care services by offering participant practices an additional per beneficiary per month payment from CMS to cover care management services. Additional performance-based incentive payments are aimed at incentivizing healthcare providers to meet other quality and utilization-focused improvements, such as lowering the hospitalization rate and improving the quality of care for attributed Medicare beneficiaries.

The Total Cost of Care model also focuses heavily on improving state-wide population health. Maryland selected six high-priority areas: Substance-Use Disorder, Diabetes, Hypertension, Obesity, Smoking, and Asthma. Noting that improving population health will increase Medicare savings in the long- and short-term, CMS will use an Outcomes-Based Credits framework to grant Maryland credits for the state's performance on these population health measures and targets. These credits will count towards Maryland's Total Cost of Care savings target and will be commensurate with the return on investment that Medicare anticipates receiving from the state's improved performance.

Though Maryland's evolving approach to hospital reimbursement has realized many successes, researchers have identified challenges to suceeding under the most recent model, namely bolstering effective communication, partnership, and collaboration between hospitals and nonhospital clinicians and facilities. In addition, close coordination between federal and state partners must play a key role in the Total Cost of Care model.35

Take-Aways From Maryland's Approach

For decades, Maryland has been the only state with an all-payer hospital rate setting system. Several researchers suggest the following as to why Maryland's system has endured:

- Stakeholder Support. The enabling legislation was drafted by the Maryland Hospital Association, an organization that was run by hospital trustees and the hospital industry has continued to support it.36

- Flexibility. The HSCRC statute merely articulated the key goals of the system but otherwise gave the Commission broad legislative authority and flexibility to develop methods to enable the system to perform and meet the goals.37

- Political and budgetary independence. The HSCRC is an independent agency led by volunteer commissioners appointed by the governor and funded through assessments on hospitals.38

Consumer Considerations

The Maryland all-payer hospital rate setting system lowered costs for patients and improved quality, particularly for high-cost, high-need patients and the most recent evaluation found that patient experience stayed the same, compared to a prior period.39

While there is no evidence of this occurring in Maryland, possible downsides to guard against under global budgets include hospital avoidance of costly or complex patients in order to meet spending targets.

More generally, consumer benefits are more likely to be realized if:

The rate setting process uses a public, multi-stakeholder process to establish rates and monitor hospital performance. Consumers and their advocates should have a formal, supported role in the process.

A robust data collection and analysis system is implemented and fully funded (out of the savings the state will realize) in order to measure the impacts on patients. Providers must receive timely, actionable reports on their performance. This data system should incorporate not only claims data but also other information, such as patient complaints made to hospitals, insurers or regulators, and patient experience survey data.

Research Needed on Administrative Cost Savings

Although theory strongly predicts administrative cost savings under this system, research is lacking to measure the impact of the all-payer hospital rate setting model on administrative costs. In a 2011 article, researchers created a model of potential savings in Vermont if the state adopted an all-payer system for hospitals. The model predicted a 7.3 percent decrease in administrative costs.40 But stronger evidence is needed to understand the impact of all-payer rate setting on hospital and insurer administrative spending compared to more conventional payment approaches.

Replicating in Other States

Like all comprehensive reforms, establishing an effective all-payer rate setting program presents a number of challenges for states.

- Avoiding regulatory capture by providers: Implement effective rate setting is very complex, requiring significant data analysis capacity. Experience with rate setting in the 1980's suggests that these conditions can lead to hospitals directing the establishment of rates.41 Successful all-payer systems will require the development of a politically independent regulatory body that is free of conflicts of interest and resistant to both industry capture and political meddling. Standards of performance imposed on the system by the federal government can increase the power of the independent agency.

- Waiver from CMS: Implementing Maryland's all-payer approach requires a waiver and any rate setting proposal cannot increase federal spending. Maryland has demonstrated that a global budgeting approach can generate overall savings for the Medicare program. In the alternative, states have the option of preserving existing discounts in the system, effectively "building in" cost-shifting, but perhaps still capping and reining in total spending.

- Concerns about increases in admissions and readmissions if global budget approach is not used: Prior experience in Maryland with a system that focused on cost per case (instead of a global budget approach) suggests that a state should be wary of possible increases in admissions and readmissions.42

- Patient impact: To stay within predefined spending limits, a hospital could feel pressure to reduce services, transfer costly patients or not admit patients with complex medical needs. Maryland attempts to prevent this through strict monitoring and potential penalties or downward adjustments to hospital budgets from the HSCRC.

In addition, regulator experts warn that it can take “three or four years for [hospitals] to make the paradigm shift into a population health approach.”43 Despite these challenges, other states are following this model closely. In 2018, no fewer than 26 states had applied to participate in a global budgeting workshop for rural hospitals.44

Currently, the effort that comes most closely to emulating the Maryland's model is the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, which began in January 2017. Under the program, participating rural hospitals are paid based on all-payer global budgets. The program pays the hospitals a fixed monthly amount and allows them to use the money how they think best serves their community. Those global payments come from several payers, including private and public insurers. The approach differs from Maryland: The private plans are not required to publicly disclose their payment rates and the state won't set the rates. Nearly half of all rural hospitals in Pennsylvania are operating with negative margins and are at risk of closure. A goal for the program is predictable revenue and spending flexibility to modify the hospital's mission to better meet community needs and stabilizing financing.

Conclusion

The success of Maryland's all-payer model provides a roadmap for how to eliminate the negative incentives of fee-for-service systems by substituting a population-based system of payment and care delivery, which is consistent with the goals of the Triple Aim and many of CMS's new payment initiatives. Hospital rate setting systems can improve patient outcomes and provide predictable revenue for hospitals, while still producing overall system savings.

It is critical that states contemplating a rate setting system similar to Maryland's include input from stakeholders, including a strong voice from consumers, providers and other organizations involved in payment and costs for care. Additionally, the rate setting body must have access to a robust data collection and analysis system to support implementation and the monitoring of progress. These strategies help to ensure the rate setting program is reducing costs and improving the patient's hospital care experience

Notes

1. Bringing in public payers requires a waiver from the federal Medicare program and also that the state Medicaid system agreed to be a part of the payment system. In Vermont, for example, Medicaid decided not to participate in a proposed multi-payer system that was designed for them. Medicaid has to agree or be mandated to be a part of the system by the legislature.

2. Murray, Robert, “The Case for a Coordinated System of Provider Payments in the United States,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law Advance Publication, Vol. 37, No. 4 (August 2012).

3. CMS, National Health Expenditure Projections 2013-2023.

4. Sisko, et al.,"National Health Expenditure Projections, 2018-27: Economic and Demographic Trends Drive Spending and Enrollment Growth," Health Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 3 (February 2019).

5. Holahan, John, et al., "Containing the Growth of Spending in the U.S. Health System," Urban Institute (Oct. 5, 2011).

6. Cooper, Zack, et al., “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured,” Health Care Pricing Project (May 2015).

7. Bai, Ge, and Gerard F. Anderson, “Extreme Markup: The Fifty U.S. Hospitals with the Highest Charge-To-Cost Ratios,” Health Affairs, Vol. 34, No. 6 (June 2015).

8. National Conference of State Legislatures, Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies NCSL Briefs for State Legislators: Equalizing Health Provider Rates All-Payer Rate Setting, Washington, D.C. (June 2010).

9. Murray, Robert, and Robert A. Berenson, "Hospital Rate Setting Revisited: Dumb Price Fixing or a Smart Solution to Provider Pricing Power and Delivery Reform?" Urban Institute, Washington, D.C. (November 2015).

10. A non-statewide program is the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, which began in January 2017. Under the program, participating rural hospitals are paid based on all-payer global budgets. More information at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/pa-rural-health-model/

11. Murray, Robert, “Setting Hospital Rates to Control Costs and Boost Quality: The Maryland Experience,” Health Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 5 (September/October 2009).

12. Ibid.

13. Cost shifting occurs when providers seek higher reimbursement rates from private payers to compensate for low reimbursement from public payers. Significant recent evidence suggests that high prices charged to private payers are the result of hospitals engaging in price discrimination (reflecting exercising their market power rather than cost shifting), but we rely on earlier reports that cost-shifting was a problem that needed addressing. See: Cohen, Harold A., Maryland's All-Payor Hospital Payment System, (2005).

14. Rajkumar, Rahul, et al., “Maryland’s All-Payer Approach to Delivery-System Reform,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 370, No. 6 (Feb. 6, 2014).

15. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Supporting Financing Mechanisms, Maryland Total Patient Review.

16. Slide deck from National Health Policy Forum, Capitalizing on Change: Improving Value and Community Health, (May 30, 2014).

17. Pines, Jesse M., et al., "Maryland's Experiment With Capitated Payments for Rural Hospitals: Large Reductions in Hospital-Based Care," Health Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 4 (April 2019).

18. Done, Nicolae, et al., "The Effects of Global Budget Payments on Hospital Utilization in Rural Maryland," Health Services Research, Vol. 54, No. 3 (May 8, 2019).

19. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Maryland All-Payer Model, (accessed on May 22, 2020).

20. Roberts, Eric, T., et al., "Changes in Health Care Use Associated with the Introduction of Hospital Global Budgets in Maryland," JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 178, No. 2 (February 2018).

21. Haber, Susan, et al., Evaluation of the Maryland All-Payer Model, Volume 1: Final Report, RTI International, Waltham, MA (November 2019).

22. Ibid.

23. Haber, Susan, et al., Evaluation of the Maryland All-Payer Model, Third Annual Report, RTI International, Waltham, MA (March 2018).

24. Ibid.

25. Health Services Cost Review Commission, All-Payer Model Results, CY 2014-2017.

26. Haber, Susan, et al., (March 2018).

27. Haber, Susan, et al., (November 2019).

28. Sabatini, Nelson, et al., “Maryland’s All-Payer Model—Achievements, Challenges, and Next Steps,” Health Affairs Blog (January 31, 2017).

29. Haber, Susan, et al., (March 2018).

30. Haber, Susan, et al., (November 2019).

31. Sharfstein, Joshua, M., et al., "Global Budgets in Maryland: Assessing Results to Date," JAMA, Vol. 319, No. 24 (June 26, 2018).

32. Haber, Susan, et al., (November 2019).

33. Sapra, Katherine J., et al, "Maryland Total Cost of Care Model: Transforming Health and Health Care," JAMA, Vol. 321, No. 10 (Feb. 21, 2019).

34. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Maryland Total Cost of Care Model, (Accessed May 22, 2020).

35. Sapra, Katherine J., et al, "Maryland Total Cost of Care Model: Transforming Health and Health Care," JAMA, Vol. 321, No. 10 (Feb. 21, 2019).

36. Healthcare Value Hub staff conversation with Robert Murray, former Executive Director of HSCRC (2014).

37. Ibid.

38. Hsiao, William, et al., “What Other States Can Learn from Vermont’s Bold Experiment: Embracing a Single-Payer Health Care Financing System,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 7 (July 2011).

39. Haber, Susan, et al., (November 2019).

40. “Has Maryland Found a Solution to the U.S. Healthcare Cost Crisis?” Beckers Hospital CFO Report (Aug. 29, 2014).

41. Murray, Robert, and Robert A. Berenson, Hospital Rate Setting Revisited: Dumb Price Fixing or a Smart Solution to Provider Pricing Power and Delivery Reform? Urban Institute, Washington, D.C. (November 2015).

42. One way around this is to apply a rate setting adjustment (used previously in MD and also in all other state rate systems) called a “volume adjustment system” that created incentives for hospitals in their payments not to unnecessarily increase admissions or other volumes.

43. Meyer, Harris, "Pa. Taps Hospitals, Payers for Rural Global Budget Experiment," Modern Healthcare (March 5, 2019).

44. Sharfstein, Joshua, M., et al., (June 26, 2018).