Marketplace Affordability: The Hazards of High Deductibles

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the federal health insurance exchange (the Marketplace) and enacted requirements mandating insurers to cover preventive services without imposing any cost-sharing obligations.a These, and other provisions included in the law, reduce out-of-pocket cost burdens and lower the risk of catastrophic expenditures.1 However, health insurance purchased on the Marketplace is still unaffordable for many consumers, particularly middle-income families.2

Premium costs are often cited as the primary reason for these affordability challenges. As a result, state and federal affordability initiatives have focused largely on reducing premium costs through subsidies for eligible consumers on the Marketplace. While these subsidies have successfully mitigated some of the financial strain, other cost-related barriers persist.3 For example, individuals enrolled in high deductible health insurance plans are responsible for high care costs before the insurer will pay for in-network covered health services.4

Consumers may find high deductible health plans attractive due to their lower monthly premium costs, and proponents have argued that high deductibles encourage consumers to make more discerning health care choices since they are responsible for the full cost of non-preventive care until the deductible is met.5

These high out-of-pocket health care costs can deter the use of both low- and high-value services, leading to a decline in high-value care utilization and leading to potentially avoidable poor health outcomes.6 For example, among individuals with bipolar disorder, high deductibles have been shown to contribute to an increase in mood symptoms, medical debt and instances where the individual avoids non behavioral health care services.7

Although being enrolled in a high deductible health plan will not always negatively impact an enrollee’s health seeking behaviors, research indicates that they do place a disproportionate financial burden on

financially insecure populations.8 To illustrate the financial burden, this brief examines the proportion of consumers' income allocated to out-of-pocket health care expenses, with a focus on how high deductibles affect affordability and access to care.

a. Common cost-sharing obligations, or out-of-pocket costs, include premiums, deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. A premium is the monthly amount paid by the insured to the insurer for coverage, a deductible is the amount the insured must pay for covered services before the insurer begins to contribute, copayments are the fixed amounts paid for specific services, such as $20 after the deductible has been met, and coinsurance is the percentage of costs borne by the insured for covered services, such as 20% after meeting the deductible.

Study Data and Methods

Data

This analysis utilized data from the integrated public use microdata sample (IPUMS) database, containing demographic and health insurance information, including premiums and out-of-pocket health expenses for individuals and households. The variables used represent demographic and health insurance information from 2019, which is the most recent year for which comprehensive data on insurance premiums and out-of-pocket expendituresis available.

Methods

We used two approaches to describe and estimate Marketplace health insurance affordability. The Marketplace Healthcare Affordability Index (MHAI) method involved calculating the share of household income the average family enrolled in Marketplace coverage spends on cost-sharing obligations, and the second examines the residual income of households after accounting for medical out-of- pocket costs (MOOP) other than premiums.

Marketplace Health Care Affordability Index (MHAI)

The first approach measured the share of household income spent on out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, such as an office visit copay. This measure is referred to as the Marketplace Healthcare Affordability Index (MHAI).

The MHAI compares the average family’s medical out-of-pocket costs to their annual income, illustrating the potential impact that Marketplace expenses have on a family’s ability to afford other basic needs, like housing, food, and childcare. Under this approach, health insurance is considered unaffordable when the average out-of-pocket costs exceed 7% and 10% of a household’s income.

These limits were chosen based on the affordability thresholds used in the Connecticut Health Care Affordability Index, which is used by the Connecticut Office of Health Strategy to understand how medical costs impact resident’s abilities to afford basic goods and services.9 Using IPUMS data, we computed the MHAI at the regional (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) and state-level for all fifty states and the District of Columbia, and then identified the number and percent of families enrolled in Marketplace health insurance coverage that spend more than 7% and 10% of their annual income on medical out-of-pocket costs.

Impoverishment Approach

The second methodology, referred to as the “impoverishment” approach, illustrates the number of households across a state or region earning more than 100% of the federal poverty level that may be pushed into poverty to afford medical care based on the average out-of-pocket costs in that geographic area. Specifically, this approach measures the residual income of households before and after accounting for the average out-of-pocket expenditures under Marketplace health insurance coverage. Households that earn above the poverty line before accounting for the average out-of-pocket costs in their state or region but drops below it after those expenditures are accounted for, is said to have been “impoverished” by the payment.

We used the United States Department of Health and Human Services poverty guidelines to determine the poverty status of families before and after incurring health care costs. For example, if a family of four in Mississippi earns more than $31,200 annually (100% FPL) prior to incurring health care costs, but whose annual income drops below this threshold after accounting for the average out-of-pocket costs incurred in the state, they would be considered impoverished due to the associated expenses. Since the majority of states and the District of Columbia have expanded Medicaid eligibility beyond 100% of the federal poverty level, we focused on those that have not — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Results

Marketplace Health Care Affordability Index (MHAI)

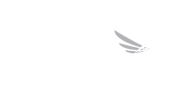

Nationwide, households spent an average of 4% of their income on out-of-pocket health care costs in 2019. However, one in every five (20% of) households spent more than 7% of their income on out-of pocket health costs, and 15% of households spent more than 10% of their annual earnings on out-of pocket costs. Based on these thresholds, even under the more conservative measure categorizing affordable as spending 10% or less of their annual income, out-of-pocket costs remained unaffordable for approximately 1.25 million households across the country. Among these families, any additional expenditure on health care imposed a substantial financial burden (see Table 1).

Table 1. Number of Households Spending More than the Affordability Threshold on Out-of-Pocket Costs by Region, 2019

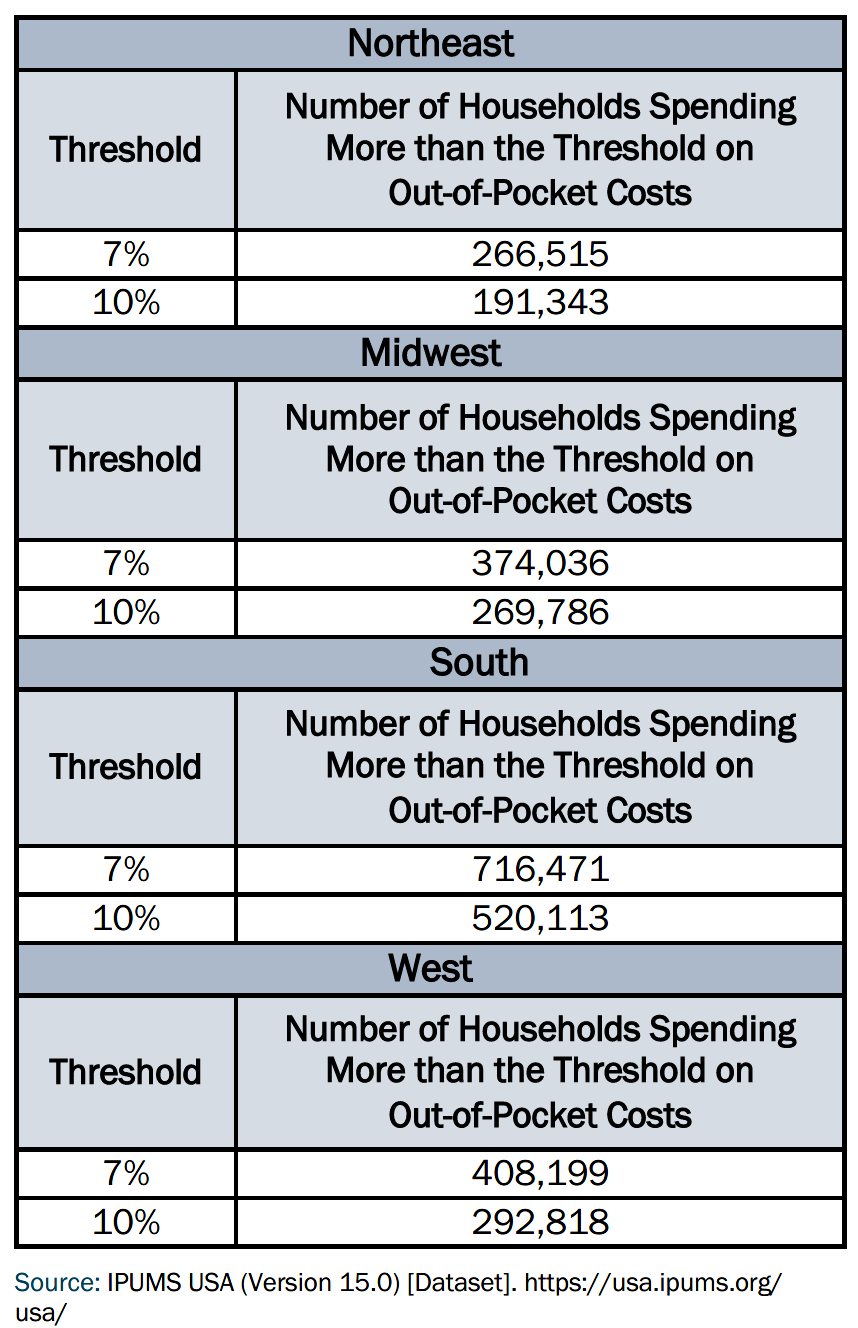

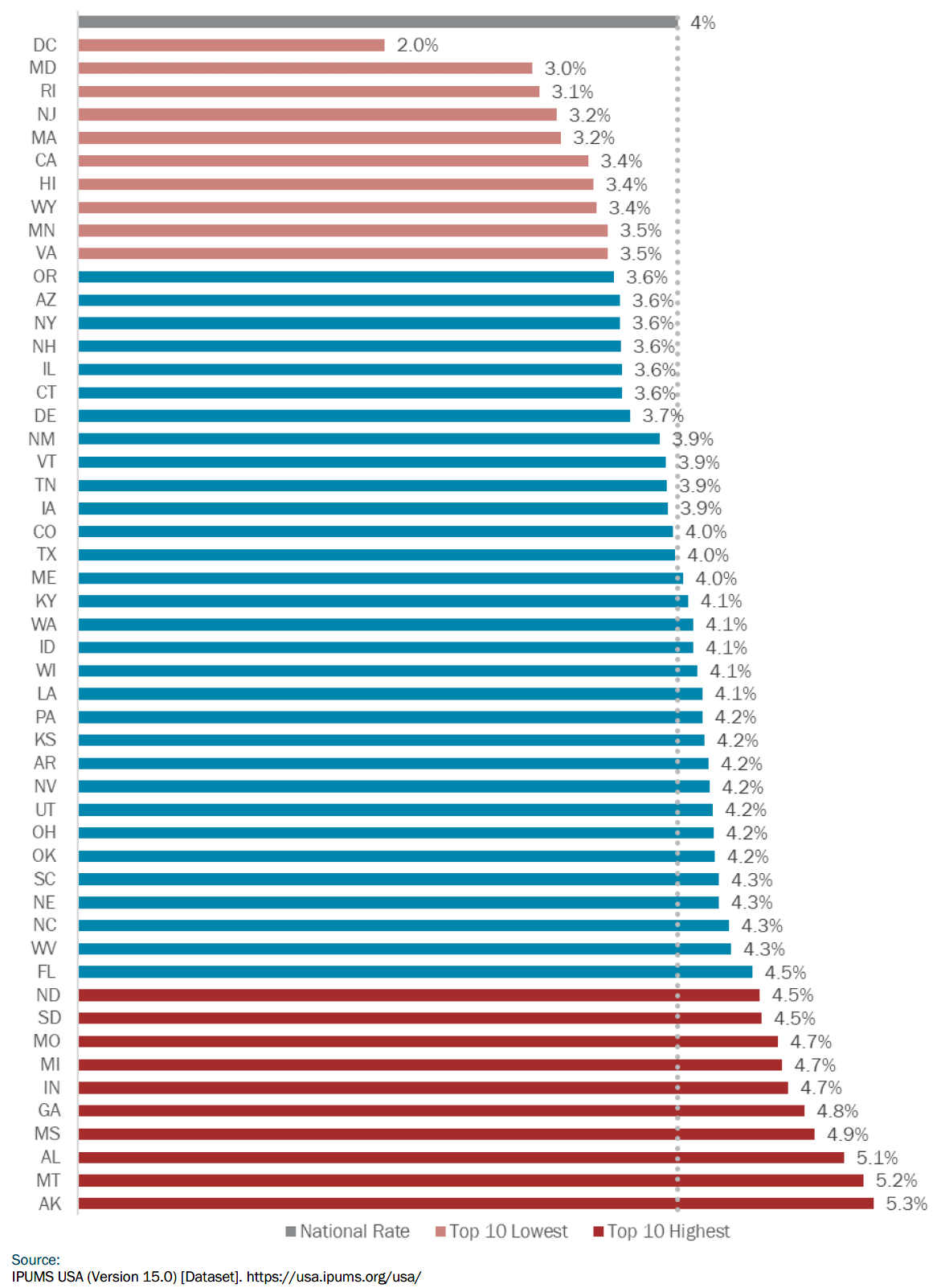

The variability in the financial burden across different regions and states was minimal, with households in each state and the District of Columbia spending, on average, between 2% and 5.3% of their household income on medical out-of-pocket costs. In most states, the proportion of income devoted to out-of-pocket costs ranged from 4% to 5% (see Figure 1). Households in Alaska experienced the highest burden, with out-of-pocket costs accounting for 5.3% of the average household income, while residents in the District of Columbia faced the lowest burden, with these costs representing only 2% of the average household income (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. State-Level Marketplace Affordability Index Variability by Quartile, 2019

Impoverishment Approach

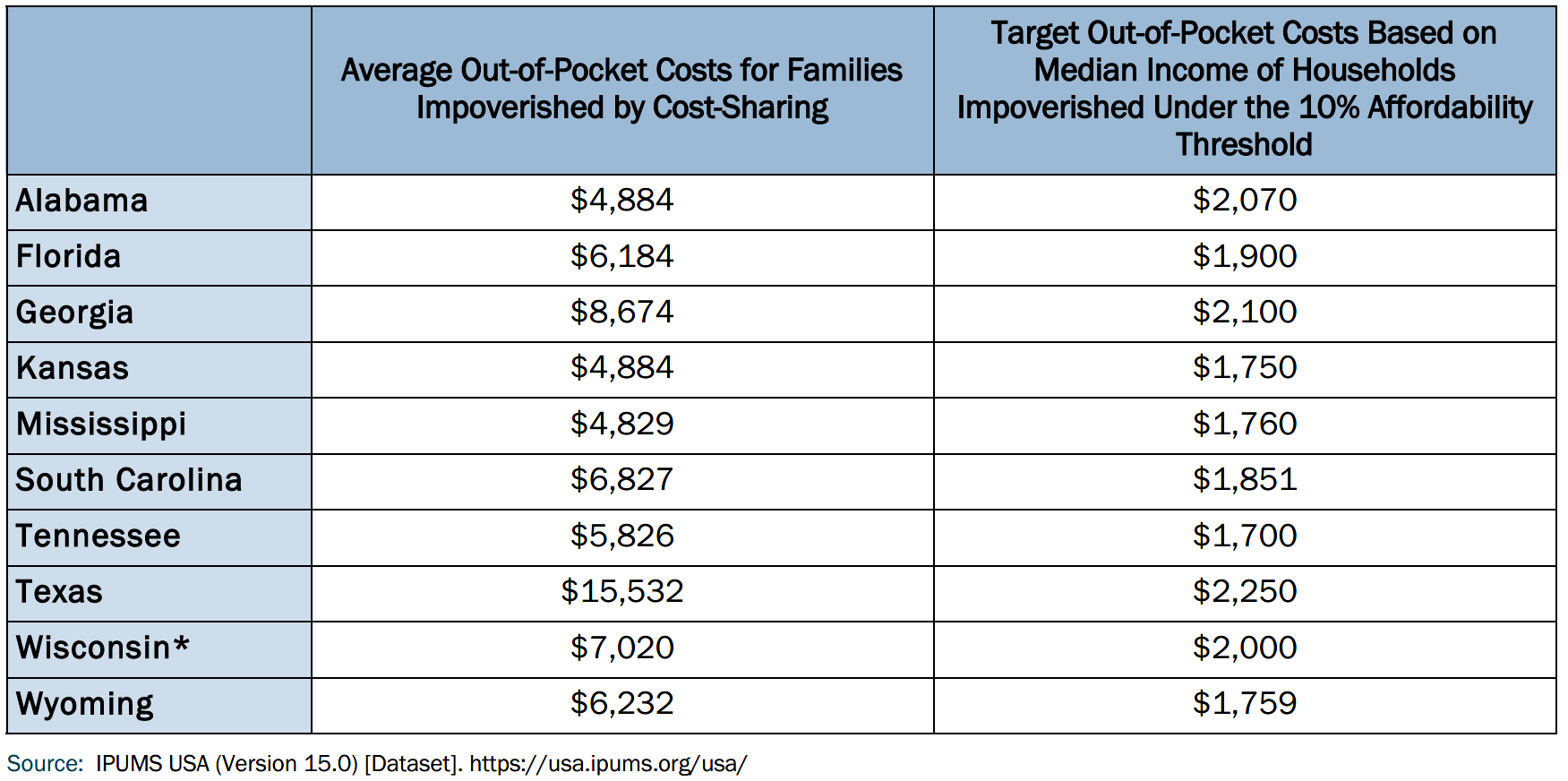

Using the impoverishment approach, which measures the residual income of households before and after accounting for the average medical out-of-pocket costs, like copayments, we found that out-of-pocket costs for medical care in non-expansion states can push individuals living above the federal poverty level below the threshold. By our measure, 12,777 households across Alabama (2,539), Mississippi (1,366), and Texas (8,872) would have been driven below the federal poverty level based on the average amount of cost-sharing obligations. Across all non- expansion states, the average out-of-pocket costs for households impoverished by their cost-sharing obligations was approximately $7,000 a year, with variations across non-expansion states (see Table 2).

The cost burden was highest in Texas where households being pushed below the federal poverty level incurred, on average, $15,532 in out-of-pocket costs. In contrast, these households in Mississippi experienced the least financial burden from out-of- pocket costs, where the average out-of-pocket costs incurred among families that were pushed below the federal poverty level by medical costs was 4,829. When examining all states, including those that have not expanded Medicaid, we found that an additional 1% of households (107,427 households) nationwide were driven into poverty due to out-of-pocket health care costs while enrolled in Marketplace coverage. Notably, nearly half (45%) of the households pushed below the federal poverty level were in the southern region of the United States, where most non-expansion states are situated.

Figure 2. Average Percentage of Household Income Spent on Out-of-Pocket Costs Among Marketplace Enrollees by State, 2019

Table 2. Average and Target Out-of-Pocket Costs for Families Impoverished by Cost-Sharing Using a 10% Affordability Threshold, 2019

Discussion

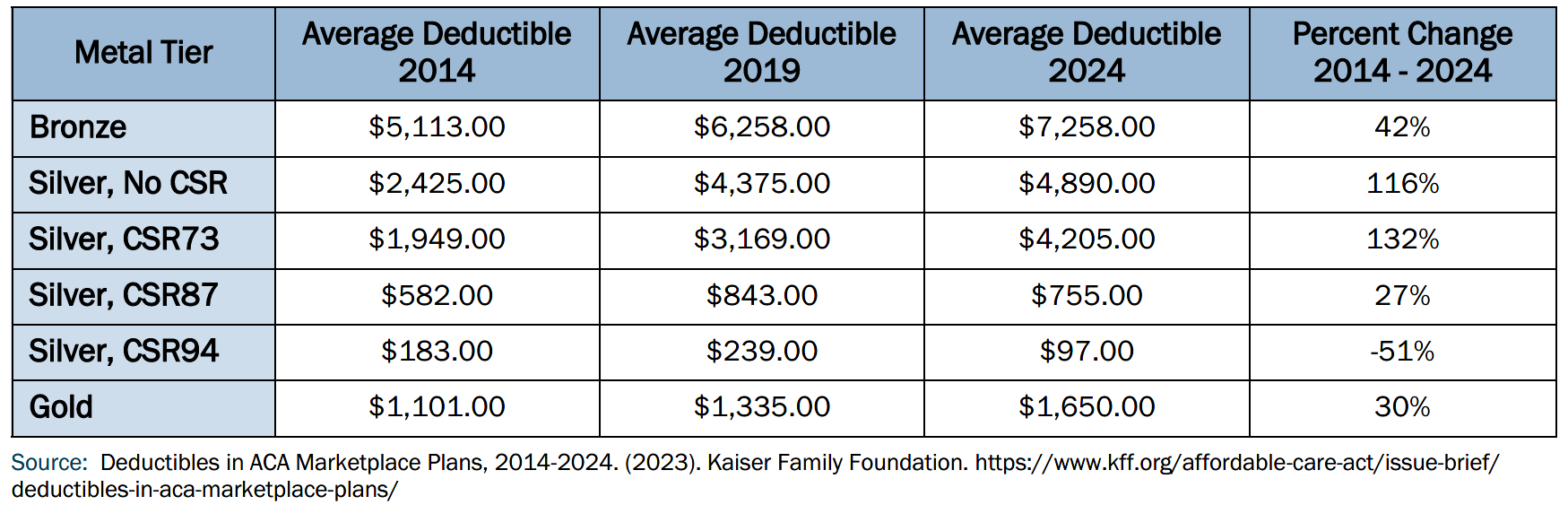

High out-of-pocket costs impact both financial stability and health outcomes, leading many to forgo necessary care due to cost concerns while others accumulate medical debt for necessary treatments. For the 2024 plan year, the out-of-pocket limit for a Marketplace plan was set to $9,450 for an individual and $18,900 for a family. Our analysis indicates that for these plans to be considered affordable, the maximum out-of-pocket limit would need to be lowered substantially. Our analysis also builds on extensive existing research illustrating the scale of this issue. High deductibles, in particular, continue to be a common cost-sharing burden among Marketplace enrollees, with the average deductible across Marketplace plans increasing across nearly all metal tiers in the last decade, save for CSR94 plans (see Table 3).

Table 3. Average Marketplace Deductible Cost by Metal Tier, 2014, 2019, 2024

Various strategies have emerged to address affordability challenges arising from high deductibles in the last several decades, including the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which introduced income tax subsidies for health savings accounts (HSAs) when paired with high-deductible health plans.10

However, despite these efforts, high deductible health plans continue to negatively impact preventive care seeking behaviors.

For example, high deductible health plan enrollees with diabetes are more likely to delay care for major symptoms of macrovascular disease, diagnostic testing, and treatment.11 Research suggests that these delays may contribute to the increased odds of experiencing various diabetes complications among individuals who transition to a high-deductible health plan, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for heart failure, end-stage kidney disease, lower-extremity complication, proliferative retinopathy, and blindness.12

Similarly, high deductible health plan enrollees with bipolar disorder receive mental health care from non-psychiatric mental health providers less frequently and navigate elevated out-of-pocket cost burdens for essential medications compared to their peers enrolled in alternative coverage types.13,14 Likewise, higher cost-sharing has also been shown to be associated with a lower likelihood of antipsychotic medication adherence and a shorter time to discontinuation among enrollees with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.15

Several states have enacted policies to reduce cost burdens, such as Connecticut, which has established an affordability standard that calculates the income necessary for a family to meet their basic needs, like food, housing, childcare, and transportation, in addition to health insurance costs. Similarly, Vermont has issued draft guidance to include affordability in the state’s premium rate review process, where a health insurance plan is considered “affordable” when the premium costs are below federal standards and the combined deductible (i.e., for both medical and prescription drug costs) does not exceed 5% of household income.

Massachusetts uses state funds to provide additional cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) for individuals with incomes up to 500% FPL. Individuals who were covered by the plans with the additional state CSRs had lower out-of-pocket costs and were less likely to report delaying or going without health care due to cost than individuals with coverage supported with only federal CSRs and overall Massachusetts residents. Likewise, California also uses state funding to provide additional cost-sharing reductions in Silver CSR plans on the Marketplace, which eliminates deductibles in those plans. California estimates that the cost-sharing reductions have improved access to affordable coverage for over 800,000 residents.

Out-of-pocket costs remain a significant financial burden for many consumers, especially those in high-deductible health plans. The analysis highlights the disproportionate impact on low- and middle-income families, revealing that a substantial portion of households spends more than 7% or even 10% of their annual income on out-of-pocket healthcare costs, deeming it unaffordable. In particular, the impoverishment approach demonstrated how high cost-sharing can push families, even those above the poverty line, into financial distress.

Given these challenges, state policy solutions may be necessary to mitigate the financial strain. Efforts such as Connecticut's affordability standard, Vermont's premium rate review process, and Massachusetts' additional state-funded cost-sharing reductions demonstrate promising approaches to reducing the impact of high out-of-pocket costs. Nonetheless, addressing this issue will require continued innovation in both state and federal policy, especially in non-expansion states, to reduce cost-sharing burdens and promote equitable access to health services.

Sources

- Lui, C., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Weiser, T., Morris, A., Tsugawa, Y. (2021). Impact of the Affordable Care Act Insurance Marketplaces on Out-of-Pocket Spending Among Surgical Patients. Annals of Surgery 274(6), e1252-e1259. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003823

- Jacobs, P., Hill, S. (2021). ACA Marketplaces Became Less Affordable Over Time for Many Middle-Class Families, Especially the Near-Elderly. Health Affairs 40(11), 1679-1816. https:// doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00945

- Liu, C., Gotanda, H., Khullar, D., Rice, T., Tsugawa, Y. (2021). The Affordable Care Act’s Insurance Marketplace Subsidies Were Associated with Reduced Financial Burden for U.S. Adults. Health Affairs 40(3), 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01106

- Glied S.A., Ly D.P., Brown, L. D., North J. (2020). Health savings accounts in the United States of America. In: Thomson S, Sagan A, Mossialos E, eds. Private Health Insurance: History, Politics and Performance. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Cambridge University Press. 525-551. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139026468.016

- Maciejewski M.L., Hung A. (2020) High-Deductible Health Plans and Health Savings Accounts: A Match Made in Heaven but Not for This Irrational World. JAMA Netw Open.3(7):e2011000. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11000

- Manning, W. G., Newhouse, J. P., Duan, N., Keeler, E. B., & Leibowitz, A. (1987). Health Insurance and the Demand for Medical Care: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment. The American Economic

Review, 77(3), 251–277. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1804094 - Madden, J. M., Araujo-Lane, C., Foxworth, P., Lu, C. Y., Wharam, J. F., Busch, A. B., Soumerai, S. B., & Ross-Degnan, D. (2021). Experiences of health care costs among people with employer-sponsored insurance and bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 281, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.033

- Glied S.A., Ly D.P., Brown, L. D., North J. (2020). Health savings accounts in the United States of America. In: Thomson S, Sagan A, Mossialos E, eds. Private Health Insurance: History, Politics and Performance. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Cambridge University Press. 525-551. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139026468.016

- Manzer, L., Brolliar, S., Kucklick, A. (2024). Connecticut Healthcare Affordability Index: 2024 Update. University of Washington School of Social Work Center for Women’s Welfare. https://selfsufficiencystandard.org/wpcontent/uploads/2024/09/CHAI2024_Summary.pdf

- Stoltzfuls-Jost, T., Hall, M. (2005). The Role of State Regulation in Consumer-Driven Health Care. American Journal of Law and Medicine 31(4), 395-418. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlufac/39/

- Wharam, J. F., Lu, C. Y., Zhang, F., Callahan, M., Xu, X., Wallace, J., Soumerai, S., Ross-Degnan, D., & Newhouse, J. P. (2018). High-Deductible Insurance and Delay in Care for the Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. Annals of internal medicine, 169(12), 845–854. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3365

- McCoy, R. G., Swarna, K. S., Jiang, D. H., Van Houten, H. K., Chen, J., Davis, E. M., & Herrin, J. (2024). Enrollment in High-Deductible Health Plans and Incident Diabetes Complications. JAMA network open, 7(3), e243394. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3394

- Wharam, J. F., Busch, A. B., Madden, J., Zhang, F., Callahan, M., LeCates, R. F., Foxworth, P., Soumerai, S., Ross-Degnan, D., & Lu, C. Y. (2020). Effect of high-deductible insurance on health care use in bipolar disorder. The American journal of managed care, 26(6), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43487

- Lu, C., Zhang, F., Wallace, J. et. al. (2022). High Deductible Health Plans Paired with Health Savings Accounts Increased Medication Cost Burden Among Individuals with Bipolar Disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 83(2), 20m13865. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13865

- Gibson, T. B., Jing, Y., Kim, E., Bagalman, E., Wang, S., Whitehead, R., Tran, Q. V., & Doshi, J. A. (2010). Cost-sharing effects on adherence and persistence for second-generation antipsychotics in commercially insured patients. Managed care (Langhorne, Pa.), 19 (8), 40–47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20822071/