The Office of the Healthcare Advocate: Giving Consumers a Seat at the Table

As healthcare recipients and payers (through premiums, taxes and out-of-pocket costs), consumers are the most important stakeholders in our healthcare system. Yet, all too often, healthcare policies are made without sufficient consumer input, resulting in a system that does not reflect patients’ wants and needs.1

Consumers’ difficulty understanding and using their health insurance is a primary example of our system’s failure to put patients first. In theory, health insurance is designed to protect consumers. But consumers are harmed when they are unable to understand coverage options or use their plans once they are enrolled. Consumers are also burdened by denied claims and confusion over the appeals process. To make matters worse, they often don’t know where to turn for help.2

Most states offer some form of consumer assistance to help people navigate the health insurance landscape. For many consumers, these programs are vital to decreasing otherwise insurmountable barriers to coverage and care. But consumers’ needs extend beyond just-in-time assistance. They also need a powerful representative to help policymakers understand how they can make the healthcare system work better for consumers.

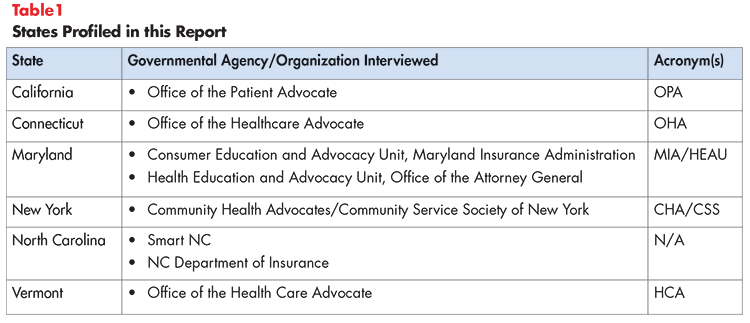

A few states, like Connecticut, are leading the way by establishing offices that not only assist consumers with their immediate needs, but advocate on their behalf to create long-term improvements as well. This brief highlights Connecticut’s Office of the Healthcare Advocate and explores best practices from five other high-performing states—California, Maryland, New York, North Carolina and Vermont (see Table 1). The information presented in this report was collected from ten discussions with consumer representatives from these five states.

Consumer Assistance is Vital, but has Limitations

Undeniably, consumer assistance is vital to achieving better healthcare value. But it largely serves as a “band-aid fix,” helping consumers navigate a complex and, at times, dysfunctional healthcare system once problems arise. Consumer advocacy offices can take consumer assistance further in two ways:

- Looking across the spectrum of healthcare consumers (private and publicly insured) to understand how they are experiencing the healthcare system.

- Attempting to influence policy to prevent pervasive problems and bring about large-scale change.

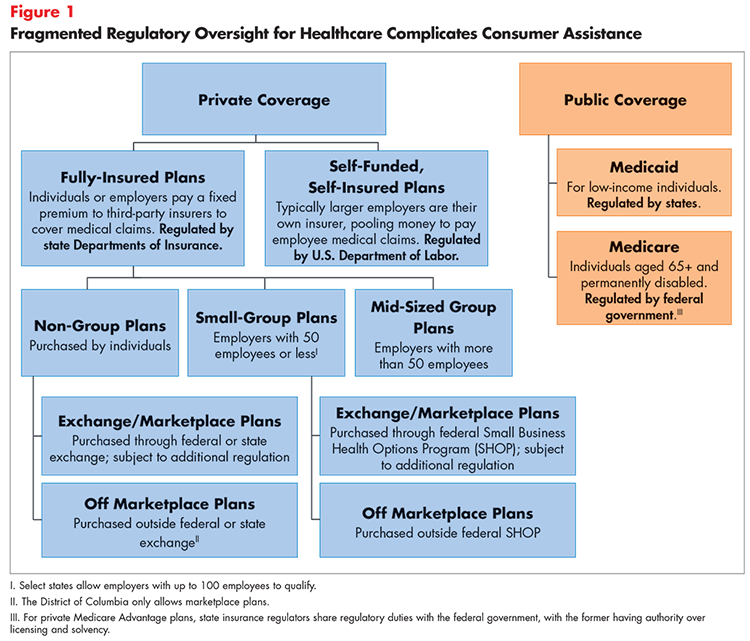

In many states, consumer assistance resources are highly fragmented. For example, it is common for a state’s department of insurance (DOI) to assist people who are insured through the individual market or their fully-insured employer. Insurance departments typically do not help consumers covered under self-insured employer plans, which are regulated by the U.S. Department of Labor. Problems with Medicare and Medicaid coverage are addressed by other entities—creating significant confusion over where consumers should turn for help (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the data collected by these entities are often unstandardized and limited to specific segments of the population, preventing policymakers and other stakeholders from obtaining a comprehensive view of the state’s coverage environment.

How Consumer Advocacy Offices Help

For maximum effectiveness, consumers need a representative body that works across all coverage types (including the uninsured) to provide one-stop assistance and identify the full spectrum of problems preventing consumers from finding and using their healthcare coverage. Additionally, the entity must have a strong relationship with the state legislature and other relevant stakeholders to provide a credible and compelling voice in the policymaking process. These two functions are central to Connecticut’s Office of the Healthcare Advocate.

What is Connecticut’s Office of the Healthcare Advocate?

In Connecticut, the Office of the Healthcare Advocate (OHA) is the primary consumer assistance agent, helping consumers find and understand their health plans, in addition to resolving coverage disputes.3 The office helps all types of consumers—regardless of whether they are on Medicaid, Medicare, privately insured or uninsured—and serves as the official voice of the consumer in front of the state legislature.

Structure

The OHA was established by the Connecticut General Assembly in 1999. It is overseen by the “Healthcare Advocate,” who serves in the role for a four-year, renewable term. The Healthcare Advocate is an appointed position. He or she must be recommended by a bipartisan advisory committee, nominated by the governor and confirmed by the General Assembly.4 This process, along with a term that typically overlaps two gubernatorial terms, helps the office remain politically neutral. Additionally, the four-year appointment allows the Healthcare Advocate adequate time to identify problems and advocate for solutions, including some that may be controversial.5

The OHA is nested within Connecticut’s Department of Insurance for administrative purposes only. The DOI has no authority or oversight over the OHA’s function as an independent industry watchdog. Interviewees generally supported this structure, with the caveat that the OHA’s structural association with the DOI could cause perceived conflicts of interest among those critical of the department’s negotiations with insurers. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this perception has occurred.

Establishment by statute has ensured that the office receives widespread support among the state legislature. The OHA is considered a trusted resource that legislators and their staff can turn to for information. Legislative offices on both sides of the aisle have also become a primary source of referrals when they are contacted by constituents struggling to obtain or use their health insurance.

Funding

The OHA is funded through assessments paid by insurers selling health plans within the state. These assessments are collected by the DOI and a portion is allocated to the OHA each year by the General Assembly. Interviewees approved of this process, noting that funding not derived from general revenue increases the office’s stability by insulating it from potential budget cuts.

Scope of Services

The OHA provides a number of services directly to consumers, such as helping with plan selection, answering questions about enrollment and guiding consumers through the referral and pre-authorization processes. The majority of staff-hours are dedicated to helping consumers appeal denied claims. Often, the OHA represents consumers in their communications with insurance carriers, using its official capacity to negotiate better outcomes than consumers could have achieved on their own. In 2016, the OHA assisted more than 7,000 consumers, helping save them approximately $11 million.6

The OHA is statutorily required to report consumer assistance data to inform policymakers on how well consumers with all types of coverage are faring in the state’s health insurance market. The office’s annual report to the governor and legislative committees offers insights on the most common problems impacting consumers by coverage type, in addition to testimonials from individuals the office has helped. One limitation mentioned by respondents is that the report does not include complaints fielded by the DOI, insurers or providers. Omission of these complaints makes it difficult for legislators to fully understand the depth and breadth of consumers’ experiences.

To further strengthen their voice in the legislative process, the OHA mobilizes consumers to testify in support of, or opposition to, various bills. The office has successfully advocated for a number of consumer protections, including requiring providers to notify patients of facility fees and educate them on the potential financial implications of being admitted under observation status.7 In 2009, the office intervened in the DOI’s rate review process, urging the department to consider the impact of rate increases on coverage affordability for consumers. While the DOI expressed that it did not have the authority to consider affordability in its review, it ultimately approved a significantly lower increase than the insurer in question had requested. Historically, the DOI had not typically denied insurers’ requested rate increases, thus the OHA’s efforts were considered a success.8

Perspectives from Other States

State-established consumer advocacy offices like Connecticut’s have a unique advantage when it comes to amplifying consumers’ voices in the policymaking process. However, it is important to acknowledge other states’ efforts to protect consumers as well. Of the states surveyed for this report, California, New York and Maryland’s models most closely resemble Connecticut’s in that they represent all types of healthcare consumers in communications with the state legislature. North Carolina’s model is focused less on advocacy and targets specific segments of the population but is a strong consumer assistance program that is worthy of recognition.9

Vermont's Office of the Health Care Advocate

Vermont’s Office of the Health Care Advocate (HCA) was established by the state legislature in 1998. Unlike in Connecticut, Vermont’s consumer advocacy office is a non-governmental entity that is housed within a statewide nonprofit law firm called Vermont Legal Aid.

The HCA provides both direct assistance and policy advocacy to benefit the state’s healthcare consumers. Consumer assistance services include helping individuals enroll in coverage and access care, educating them on covered benefits and helping them file grievances and appeals. The office also advises on billing and coverage disputes and educates consumers on their rights and responsibilities under the law. The HCA serves individuals with all types of healthcare coverage (including the uninsured) and saved Vermonters more than $260,000 in fiscal year 2017.10

As the official voice for Vermont’s healthcare consumers, the HCA is actively involved in a variety of policy and regulatory discussions. To raise the profile of consumer coverage and affordability problems, the office prepares regular reports presenting findings to the state legislature and relevant agencies, and recommending potential solutions. For example, the HCA’s consumer assisters have long been aware of a critical need for improved access to dental care, particularly among children, seniors and Medicaid beneficiaries. To help address this need, the office participated in a coalition that successfully advocated for the creation of a new class of dental provider (called dental therapists) licensed to provide basic services. The HCA also comments on proposed state and federal legislation and rules, and serves on various task forces, councils and work groups impacting consumers’ access to high quality care. This involvement includes participation in the development and implementation of healthcare pilot projects, where consumer representation is vital and too frequently absent.

The HCA has several unique authorities compared to a traditional nonprofit that increase its ability to help consumers. During the state’s annual insurance rate review, the HCA has the right to be copied an all materials (including those designated as confidential), and can submit questions to insurers, present witnesses at hearings, cross examine insurers’ witnesses and submit post-hearing memos. The HCA can also request further review of decisions that it deems unfairly burdensome to consumers.

To contain provider-driven costs, the HCA participates in the state’s hospital and accountable care organization budget reviews. Throughout these processes, the HCA is copied on all materials, and can submit written questions, question the organizations’ witnesses at hearings and submit post-hearing comments. The office also participates in administrative and judicial review of certificate of need applications and can take legal action to “enjoin, restrain or prevent” violations of certificate of need laws.

Interviewees expressed that there are both advantages and disadvantages to HCA’s nonprofit status. A significant advantage, according to the HCA’s annual report, is that independence from political or bureaucratic pressures enables the HCA to serve as a true watchdog for the state’s healthcare consumers. For example, over the past few years the office has worked with a coalition of organizations to challenge the Vermont Medicaid program’s “overly restrictive and illegal” criteria preventing beneficiaries with Hepatitis C from accessing curative treatment. As a result, some criteria have been eliminated, reducing major barriers to life changing care.

One disadvantage of nonprofit status, however, is that it can make it difficult or impossible to access valuable state-collected data. This is an important limitation because it can prevent non-governmental advocacy offices from conducting critical analyses to inform advocacy efforts and help stakeholders better understand the quality of care that consumers receive. Interviewees also acknowledged the possibility that being housed outside of state government could affect how the office is viewed by state agencies and their staff, although this was not considered a significant concern.

California’s Office of the Patient Advocate

As in most states, California has a number of agencies that assist healthcare consumers. The California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) is the primary consumer assistance agency, operating a help center to understand, investigate and address consumers’ coverage issues, regardless of coverage type.10 The DMHC also contracts with Health Consumer Alliance organizations to help all healthcare consumers overcome barriers to coverage and care.12 Additional assistance is provided for select groups of consumers through the state’s DOI, Department of Health Care Services (California’s Medicaid agency) and Covered California (the state’s individual exchange). Collectively, these entities addressed approximately 30,000 complaints in 2015.13

The DMHC, DOI, Department of Health Care Services and Covered California are statutorily required to submit consumer assistance data to the Office of the Patient Advocate (OPA) each year. As of 2014, the OPA is charged with aggregating consumer assistance data into an annual report that is submitted to the state legislature.14 The purpose of this report is to help legislators identify and address coverage problems burdening consumers.14

Interviewees noted challenges to California’s model, primarily stemming from a lack of data standardization between the four departments that help consumers. Because the OPA does not provide consumer assistance directly, it must rely on these entities to collect the necessary data. Currently, data collection is unstandardized, meaning that the information collected is not the same across consumer populations. Lack of data uniformity prevents information from being aggregated across populations to create a comprehensive picture of consumers’ experiences. The OPA is currently working with the departments to standardize data collection in order to improve the usefulness of its report.

The OPA is unique in that it also increases transparency on healthcare quality, informing consumers and other stakeholders on how the state’s commercial health plans and contracted medical groups perform in terms of quality, cost and patient experience.16 This role combined with the office’s duty to report on consumers’ ability to find and use their health coverage has the potential to provide a unique understanding of how well the state’s healthcare system works for consumers. However, despite the fact that the agency is required to post quality information on its website, it is not required to report its findings to the state legislature.

New York’s Community Health Advocates

New York’s consumer advocacy model is different from the others profiled in this report in that it relies heavily on community-based organizations (CBOs) to provide consumer assistance, in addition to governmental agencies. In New York, consumer assistance is delivered by a network of approximately 26 nonprofit CBOs—known collectively as Community Health Advocates (CHA). The network is coordinated and supported by the Community Service Society of New York (CSS), along with three expert specialist partners.17,18

The CBOs offer a variety of services to help New Yorkers with all coverage types overcome barriers to coverage and care, including health insurance literacy education and referrals to low cost or free clinics. They also communicate directly with insurers on behalf of consumers to secure medical care or prescriptions, negotiate lower medical bills and file appeals.19 The network serves approximately 30,000 New Yorkers annually, saving them roughly $6 million per year in healthcare costs.

As the coordinating entity, CSS works with the CBOs to facilitate information sharing, provide technical assistance and collect data. The organization also publishes resources for both the CBOs and consumers on its website and operates a toll-free call center to help individuals resolve problems with their health coverage. To maximize impact, CSS employs policy staff to communicate with state and local officials and work to address consumers’ needs.20

One advantage to the community-based model is that assisters employed by the CBOs are trained in and knowledgeable about the communities they serve, helping build trust between them and consumers. This is particularly true among vulnerable populations that have traditionally been difficult to reach, such as immigrant communities, the homeless and individuals with low income and/or low literacy levels. Additionally, CHA’s secure database helps standardize data collection and reporting, enabling analysts to identify trends and areas in which policy changes would benefit consumers. CSS uses these insights to inform its policy and advocacy agendas, raising public awareness and informing state and local policymakers. Interviewees also noted that CSS’s status as an independent nonprofit may allow it to advocate more tenaciously for consumers than traditional governmental assisters (e.g., state insurance departments), which must balance their adjudicatory and regulatory role between consumers and insurers.

One important tradeoff is that nonprofits do not have the regulatory enforcement or discovery powers of some government agencies. Additionally, due to their non-governmental status, they may have to work harder to establish trusted relationships with policymakers in order for consumers’ voices to be heard. Because CHA is partially funded by the state and is required to report to the administration quarterly, this is not a concern in New York. Nonetheless, it is an important consideration for states interested in replicating the model.

Maryland’s Insurance Administration and the Office of the Attorney General

Maryland, like many states, has a number of government agencies dedicated to helping consumers. In the healthcare space, these include the Maryland Insurance Administration (MIA) and the Office of the Attorney General. The MIA has two divisions that help consumers understand and use their health insurance. The department’s Consumer Complaints Division provides just-in-time assistance, investigating consumers’ complaints against insurers and guiding them through the processes for remediation. The office is also charged with ensuring that insurers comply with laws, regulations and policies and can take corrective action against companies that fail to do so.21

The second MIA division—the Consumer Education and Advocacy Unit—helps prevent future problems by working to improve consumers’ health insurance literacy and answering basic questions related to covered benefits. It also produces written materials to help consumers determine who they should contact if an issue were to arise. This function is especially important given the fact that the MIA’s jurisdiction applies only to fully-insured plans. The department does not have the authority to address problems with self-insured plans, Medicare, Medicaid or other forms of insurance, and is therefore unable to assist all consumers.

The Health Education and Advocacy Unit (HEAU) within the Attorney General’s office has broader authority to intervene in medical billing, coverage and medical equipment disputes. Not only can the office help resolve coverage denials and other problems with private insurers (including those not regulated by the MIA), but it can negotiate with providers and medical equipment distributors on consumers’ behalves as well. Additionally, the office helps consumers file appeals when they are unfairly denied premium tax credits, cost-sharing reductions or coverage through the state’s exchange. The HEAU helped Maryland consumers save approximately $3.7 million in Fiscal Year 2017.22

The HEAU is required to submit a yearly report to the legislature summarizing the appeals handled by the Unit, in addition to those handled by the MIA and individual insurance carriers. Although the Unit helps a broader swath of consumers than the MIA, it does not handle Medicaid appeals and forwards Medicare issues to local Senior Health Insurance Program (SHIP) offices. Thus, problems experienced by only a subset of consumers are conveyed in the annual report. Maryland does not have a single entity responsible for aggregating Medicare, Medicaid and private health insurance information.

In addition to its consumer assistance function, the HEAU serves as the official voice for Maryland’s healthcare consumers. The unit reviews nearly all health-related bills introduced each legislative session, filing letters supporting legislation that increases consumer protections and proposing amendments to policies that would negatively affect consumers’ access to coverage and care. The unit also files consumer-centric comments on proposed state and federal regulations, in addition to the state’s annual insurance rate review. HEAU representatives sit on a number of policy boards to represent consumers, including those on policies that impact Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.

The HEAU further helps consumers by introducing legislation through various sponsors. For example, in 2016, the unit proposed the Consumer Health Claim Filing Fairness Act, which extended the time that insurance carriers must allow consumers to file claims from 90 days to one year. The HEAU also supported the passage of the Prescription Drug Price Gouging Prohibition bill (supported by the Office of the Attorney General) prohibiting drug manufacturers and wholesale distributors from charging unreasonably high prices for “essential off-patent or generic drugs.” Both bills passed the general assembly and were signed into law.

North Carolina’s Smart NC

The North Carolina Department of Insurance has actively assisted consumers who have been denied coverage for medical procedures since 2002. In 2011, the state received federal consumer assistance program funding to expand its services, delivered under a newly created program called Smart NC. Although it is operated by the DOI, Smart NC is able to assist consumers with coverage that falls outside of the DOI’s jurisdiction—such as those covered under self-funded plans—in addition to helping the fully-insured.

For much of its existence, Smart NC provided an extensive offering of services to help consumers resolve problems with their health insurance. But after the federal funding concluded in 2016, the program narrowed its scope to focus on providing health insurance counseling and assistance filing complaints, appeals and requests for external reviews for denied claims. Services that are no longer delivered by Smart NC—such as help addressing problems related to out-of-network services and coordination of benefits—are now offered by the Consumer Services Division of the DOI. However, unlike Smart NC, the DOI is only authorized to help individuals who are fully-insured. Since 2002, Smart NC and the DOI have saved consumers more than $20 million.

Neither Smart NC nor the DOI’s Consumer Services Division handle complaints from individuals on Medicaid or Medicare. Interviewees noted a gap in state-delivered resources for the uninsured, although Smart NC facilitates connections to other consumer assistance agencies (such as navigators, coverage assisters, free clinics and charity care programs) when possible. Partnerships between Smart NC and other consumer assisters (in the form of referrals) are strengthened by participation in the Get Covered Coalition, a multi-stakeholder collaboration dedicated to decreasing barriers to coverage throughout the state.

Currently, there is no central agency responsible for aggregating the data collected by Smart NC, the DOI and the other consumer assistance agencies and reporting findings to policymakers. Rather, each entity reports information on the populations it serves directly to the General Assembly as requested or required.23 Interviewees reported that Smart NC was not established to serve as either a consumer advocacy office or the official voice of the consumer to the state legislature. To their knowledge, this body does not currently exist.

Lessons Learned

Interviewees from the five states provided a number of recommendations to guide states interested in establishing consumer advocacy offices and inform those looking to improve their current approach. Lessons learned are divided by topic in the sections below.

Structure

Establishment by statute has pros and cons. Consumer advocacy offices must have strong relationships with their state legislature in order to influence policies to benefit consumers. State-established advocacy offices have an advantage in that they are formed to be the eyes and ears of the legislature, which automatically grants them a certain level of trust and support. Furthermore, establishment by statute could theoretically afford these offices special powers beyond the scope of a non-governmental entity, such as the ability to compel third parties appear before them or to produce important documents (i.e., subpoena powers).

However, it is also important to note potential challenges for interested states to consider. Although governmental advocacy offices represent consumers’ interests first and foremost, they may be perceived by some as being constrained by political influences. All interviewees firmly believed that state-established offices should be independent from political parties to maximize their loyalty to consumers. Requiring that the department’s leader (a.k.a., the Advocate) be elected by the general public or nominated by a bipartisan committee will help ensure that the office remains politically neutral. Structuring the Advocate’s term so that it overlaps with two gubernatorial administrations can also help maintain independence.

Governmental advocacy offices should also be cognizant of the perception that they can be influenced by powerful stakeholder groups. For example, some interviewees felt that operating within a state’s insurance department may be perceived as a conflict of interest due to their regulatory relationship with insurers. Connecticut has attempted to mitigate this risk by barring OHA employees from owning, managing, licensing or investing in managed care organizations. Additionally, OHA employees are prohibited from working for a managed care organization for one year after they leave the office.

Community-based organizations access hard-to-reach populations. Governmental advocacy offices primarily rely on data collected from hotlines to understand how well consumers are navigating the health insurance landscape. This information is valuable, but only provides insights on the experiences of relatively well-informed consumers who knew where to turn for help. But many consumers—such as those with low education/literacy levels and immigrants—may be unaware of available resources. Lack of information on the obstacles faced by these populations may cause important problems to remain unaddressed.

Community-based assisters are better able to meet these consumers’ needs by offering services where they live and work. These assisters are trained in and knowledgeable about the communities they serve, helping establish trust with consumers. As a result, they are better-positioned to understand and advocate for hard-to-reach populations, which are frequently underrepresented in the dialog.

Funding

Insurance assessments help ensure sustainability. Ideally, states would establish permanent funding for consumer advocacy offices to signify their commitment to helping consumers effectively navigate the healthcare system. This may be difficult, however, given pressure on state budgets. Interviewees cited pros and cons to financing through assessments on insurers (as is done in Connecticut), but ultimately supported the model. They explained that funding streams independent of general revenue improve the offices’ stability by insulating them from potential budget cuts.

Lack of funding limits impact. When asked to identify the greatest barrier to realizing their full potential, multiple respondents cited limited funding. Specifically, interviewees noted a dearth of funds for consumer outreach through paid advertising or testing consumer awareness of their offices. However, interviewees also expressed doubt that their offices could handle additional volumes of consumers (due to their small staff sizes) should greater funding for outreach be made available.

Scope of Work

Consumer assistance and advocacy go hand in hand. For decades, most states have provided assistance to help consumers resolve problems finding and using their health insurance. While incredibly valuable, these services do not address the root causes of consumers’ difficulties, allowing systemic failures to persist. A few states have attempted to prevent pervasive problems from re-occurring by strengthening consumers’ voice in the legislative process. By ensuring adequate representation for consumers, these states will be better positioned to improve healthcare value over time.

Conversely, it is difficult for advocacy offices to adequately express the depth and breadth of consumers’ experiences to policymakers without regular contact with the individuals they serve. Advocacy offices that provide consumer assistance have first-hand knowledge of consumers’ problems and are therefore best suited to represent them in communications with the state legislature. Ultimately, consumers will benefit most from an office that combines these functions to address both their immediate and long-term needs.

Data standardization gives all consumers a voice in the policymaking process. As the official voice of the healthcare consumer, advocacy offices have a duty to represent individuals with all coverage types, including the uninsured. Ideally, states would establish a single entity to provide consumer assistance, ensuring complete standardization of the data collected across populations. This would allow analysts to aggregate the data to form a comprehensive picture of how well all consumers are faring in the coverage marketplace and identify areas for improvement. Gaining these insights is a greater challenge in states where consumer assistance is not provided by a single entity, as data collection is more likely to be unstandardized. The inability to aggregate data makes it difficult to identify the predominant issues plaguing all types of healthcare consumers and convince legislators of the need for wide-scale change.

Healthcare affordability (and other problems) must also be addressed. Surveys show that healthcare affordability is a top-of-mind consumer concern.24 Nationally, 21 percent of families faced a high medical cost burden (defined as spending more than 10 percent of income on medical care) in 2016.25 Although all of the offices surveyed help consumers appeal denied claims and negotiate lower medical bills, many reported that improving overall healthcare affordability is not currently an area of focus. This is a significant shortcoming, as consumers cannot have meaningful access to health insurance as long as they struggle to afford their premiums, deductibles and copays.

Additionally, consumers would benefit from a representative who is knowledgeable about the quality of care they receive for the money they spend. It is well documented that healthcare quality is vastly uneven, both geographically and by patient population.26 For example, the Commonwealth Fund’s 2017 Scorecard on State Health System Performance revealed that Medicare beneficiaries in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Mississippi and New Jersey were four times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients in Hawaii. The report also found that, in every state, African Americans under age 75 were more likely to die from treatable conditions than whites and Hispanics.26 Of the models surveyed, California’s Office of the Patient Advocate is the only entity whose scope suggests incorporating this information into the consumer experience narrative.

Consumers do not experience the healthcare system in silos. From their perspective, coverage, affordability and quality are intertwined. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that consumer representatives understand and, more importantly, be able to express to the legislature how problems in each of these areas make it difficult for consumers to find and receive care. Decreasing coverage barriers is important, but consumers’ affordability and quality concerns must also be addressed.

Collaboration with other stakeholders is important. Consumer advocacy offices should look for opportunities to collaborate with stakeholders beyond the state legislature, particularly those that also assist consumers. These include DOIs, state Medicaid departments and insurance exchanges, in addition to offices that may be unique to a state, such as California’s Department of Managed Care. Not only can these agencies be important referral sources, but many collect consumer assistance information that is vital to the role of the healthcare Advocate.

Because consumer advocacy offices help the same populations as other, more traditional assisters, there is often considerable overlap of responsibilities. This has the potential to breed competition and create conflict. Although establishing a consumer advocacy office to assist all consumers has a number of benefits, it is important to recognize situations in which other entities may be better suited to help. For example, DOIs can better serve consumers when commercial insurers fail to meet certain requirements (such as covering mandatory benefits) due to their legal authority to compel insurers to comply. Thus, it is essential for consumer advocacy offices to maintain positive relationships with other entities to ensure that handoffs flow as smoothly as possible.

Regularly sharing information could help build the necessary atmosphere of trust. Currently, it is common for consumer complaints to be recorded and reported to the legislature separately by each consumer assistance agency. However, merging the information into a single document containing complaints reported to all consumer assistance agencies would provide legislature with a clearer picture of how consumers are faring in the market. Ideally, this report would also include complaints collected by insurers and providers, although interviewees expressed that insurers may be unwilling to provide this information and they could not envision a way of systematically aggregating complaints to providers.

Consumer Outreach

“Listening tours” can shed light on consumers’ experiences. Connecticut’s Healthcare Advocate conducted a listening tour in 2017, traveling the state to gain first-hand knowledge of consumers’ experiences with the healthcare system. The tour was designed to help the Healthcare Advocate understand the depth and breadth of consumers’ issues in order to report persistent problems to policymakers and recommend potential solutions. Additionally, consumers were encouraged to offer recommendations to make healthcare more affordable, including strategies to reduce both the cost of health insurance and medical services.

Listening tours in the form of “town halls” are regularly used in politics but are a somewhat novel approach for government agencies. They may be especially useful for consumer advocates in large states and/or states with populations that vary drastically (demographically or ideologically) by geography.

Consumers must be targeted at the right time and place. Some interviewees noted that it can be difficult for consumer assisters to determine when and where to target outreach efforts. Respondents explained that many consumers are not interested in learning about consumer advocacy offices until they need help. Thus, it is vital for the offices to identify the best stakeholder to have this information on-hand, readily available at the time and place consumers need it most.

Several interviewees reported that insurers selling plans in their states are statutorily required to provide contact information for consumer assistance agency on notices sent to consumers when a service is denied. All felt this was an important consumer protection that effectively targets those in need. However, one respondent noted that this information is often published several pages into the text-heavy and linguistically complex document, after the point at which many consumers stop reading. Requiring insurers to publish contact information at the beginning of the notice would increase the likelihood that consumers will find it.

Legislators and their staffs are frontline responders. A number of respondents cited members of the state legislature and their staff as a primary source of referrals for consumers having trouble finding and using their health insurance. Often, these offices receive calls from frustrated constituents who are unsure of where to turn for help. Raising awareness among and building relationships with these legislators can help ensure that consumers are able to find assistance when they need it most. Respondents cited that policymakers often appreciate knowing that this resource is available, as it helps improve their reputations among their constituents.

Conclusion

As the most important healthcare stakeholder, consumers deserve a system that reflects their needs and preferences. Yet, all too often, they are underrepresented in policy discussions that ultimately affect their access to coverage and care. State-established consumer advocacy offices give healthcare consumers a long-awaited seat at the table by amplifying the consumer voice in front of the state legislature. The most effective offices help policymakers understand how well all consumers are finding, using and affording their health insurance, regardless of coverage type.

The majority of states offer some form of assistance to help consumers navigate the health insurance landscape, but few have gone so far as to establish offices that advocate on consumers’ behalf. Connecticut’s Office of the Healthcare Advocate serves as a powerful model for other states interested in increasing protections and representation for consumers. States can also look to the experiences of other high-performers – such as California, New York, Maryland and North Carolina – for lessons learned.

Through informal discussions with representatives from these five states, we assembled a series of insights for others to consider when establishing their own consumer advocacy offices. Important takeaways include:

- The advantages and disadvantages to establishment by statute;

- The need for a reliable funding source to increase stability;

- The benefits of combining consumer assistance and advocacy; and

- The importance of collaboration with other stakeholders.

A lack of focus on healthcare affordability and the need to target consumers at the right time and place should also be addressed.

As demonstrated in the examples above, states can exercise a high degree of flexibility when determining their offices’ structure, funding and scope of services. The right model will depend on each state’s unique policy, regulatory, advocacy and coverage environments. But no matter what forms the offices take, their mission remains the same. By giving consumers a strong and clear voice in the policymaking process, states can make great strides towards achieving better healthcare value.

Notes

1. Ditre, Joe, Consumer-Centric Healthcare: Rhetoric vs. Reality, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (March 2017).

2. A 2015 nationally-representative survey conducted by Consumer Reports found that 67 percent of consumers did not know the relevant state entity to contact to address insurance billing issues. Additionally, 87 percent of consumers did not know who to contact for health insurance complaints. For more information, see: https://consumersunion.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CY-2015-SURPRISE-MEDICAL-BILLS-SURVEY-REPORT-PUBLIC.pdf

3. Other consumer assistance entities include the Department of Insurance, the state exchange, Connecticut’s Medicaid department and the Seniors’ Health Insurance Information Program. The scope of services provided by these entities varies and are limited to specific segments of the consumer population.

4. The Office of Governor Daniel P. Malloy, “Gov. Malloy Nominates Ted Doolittle to Serve as State Healthcare Advocate,” News Release (Jan. 6, 2017). http://portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/Press-Room/Press-Releases/2017/01-2017/Gov-Malloy-Nominates-Ted-Doolittle-to-Serve-as-State-Healthcare-Advocate

5. Tracy, Carrie, Elisabeth R. Benjamin, and Christine Barber, Making Health Reform Work: State Consumer Assistance Programs, Community Service Society and Community Catalyst, New York, N.Y. (September 2010). https://www.communitycatalyst.org/doc-store/publications/Making_health_reform_work_CAP.pdf

6. Connecticut Office of the Healthcare Advocate, Annual Report CY 2016, Hartford, Conn. (2016). http://www.ct.gov/oha/lib/oha/oha_2016_annual_report.pdf

7. Connecticut Office of the Healthcare Advocate, Annual Report CY 2014, Hartford, Conn. (2014). http://www.ct.gov/oha/lib/oha/documents/publications/oha_2014_annual_report_final_-2.pdf

8. Ibid.

9. The Affordable Care Act allocated funding for states to create consumer assistance programs dedicated to helping consumers find and use their health insurance. Eventual defunding made a number of the programs unsustainable, but some states have continued to operate them using state funds.

10. Vermont Office of the Health Care Advocate, SFY 2017 Annual Report, http://www.vtlegalaid.org/sites/default/files/2017%20HCA%20Annual%20Report.pdf (accessed May 15, 2018).

11. California Department of Managed Health Care, About the DMHC, https://www.dmhc.ca.gov/AbouttheDMHC.aspx (accessed April 6, 2018).

12. Services include assistance applying for coverage, finding a physician or other healthcare provider, appealing coverage denials, resolving billing disputes and preventing lapses in care. See https://healthconsumer.org/about-us/ for more information.

13. Brown, Edmund G., Diana S. Dooley, and Elizabeth C. Abbott, Annual Health Care Complaint Data Report: Report to the Legislature for Measurement Year 2015, California Office of the Patient Advocate, Sacramento, Calif. (2017). http://www.opa.ca.gov/Documents/ComplaintDataReport-2015Data.pdf

14. Consumer assistance data collected on Medicare enrollees is not reported to the OPA.

15. In addition, being submitted to the state legislature, the report is also posted on the OPA website (www.opa.ca.gov) to inform a variety of other stakeholders. These include consumers, advocates, regulators, researchers, brokers, health plans and insurers.

16. The OPA is statutorily required to produce three healthcare quality report cards, which contain 7,500 data points to show quality trends for health plans and providers throughout the state. A star performance rating system helps users identify top performers. For information, see: http://www.opa.ca.gov/Pages/ReportCard.aspx

17. The three expert specialist partners include the Empire Justice Center, the Legal Aid Society and the Medicare Rights Center.

18. Consumer assistance is also provided by various governmental agencies and non-profit organizations. The majority of these entities exclusively assist specific subsets of the consumer population. For more information, see: https://nyshealthfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/navigators-consumer-assistance-programs-september-2011-1.pdf

19.Tracy, Benjamin and Barber (September 2010).

20.Tracy, Benjamin and Barber (September 2010).

21. Maryland Insurance Administration, File a Complaint, http://insurance.maryland.gov/Consumer/pages/FileAComplaint.aspx (accessed April 3, 2018).

22. State of Maryland Office of the Attorney General Consumer Protection Division Health Education and Advocacy Unit, Annual Report on the Health Insurance Appeals and Grievances Process, http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/CPD%20Documents/HEAU/Anual%20Reports/HEAUannrpt17.pdf (accessed April 3, 2018).

23. Note: Smart NC was originally, but is no longer, statutorily required to produce an annual report to the General Assembly. The DOI makes non-confidential information from Smart NC and its Consumer Services Division available to interested stakeholders upon request.

24. See, for example, U.S. Concerns About Healthcare High; Energy, Unemployment Low, Gallup poll (March 2018). http://news.gallup.com/poll/231533/concerns-healthcare-high-energy-unemployment-low.aspx

25. SHADAC, State Health Compare, Minneapolis, M.N. (2016). http://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/Data

26. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, Rockville, M.D. (2016). https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/overview.html#Variation

27. Radley, David C., Douglas McCarthy and Susan L. Hayes, Aiming Higher: Results from the Commonwealth Fund Scorecard on State Health System Performance, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (March 2017).