Rethinking Consumerism in Healthcare Benefit Design

For decades, rising healthcare costs have strained household, employer and government budgets. A strategy often proposed to address these high costs is to give consumers more “skin in the game,” through high-deductible health plans. When accompanied by shopping aids, these plans are sometimes called consumer-directed health plans. But a wealth of evidence suggests that high-deductible health plans are not leading to better value in our healthcare system. What’s more, unaffordable cost sharing causes considerable consumer harm. Instead, efforts to address high prices and promote high-value care must have a strong provider-directed component, because providers direct treatment plans and steer almost all of our healthcare spending. Our country needs to rethink the role of the consumer in healthcare to be fair, patient-centric and evidence-based. Consumers should be empowered with timely, accurate and actionable information to help make decisions about their care and not have their choices curtailed due to unaffordable cost sharing.

Click here to download Research Brief No. 11

Rethinking Consumerism in Healthcare Benefit Design

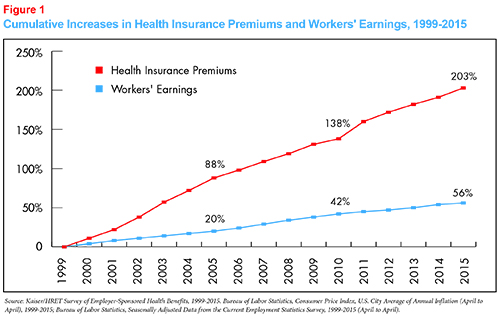

High healthcare costs are a concern for consumers and payers alike. Insurance premiums have risen faster than wages and the economy in general for nearly two decades. High levels of health spending crowds out other important spending. For households, this means lower wages and less money for competing priorities. For state and national governments, it means less to spend on education, infrastructure and other public needs. There is consensus that we can cut back on waste in the system (including prices that are too high) in order to reduce spending without harming our health outcomes.

An oft-used strategy to address high healthcare costs are insurance products called high-deductible health plans, or more generally, consumer-directed healthcare. The basic idea is that by requiring consumers to pay substantial cost sharing these plan designs will incentivize consumers’ to extract better value from the healthcare marketplace, helping to stem the tide of rising healthcare costs and reducing the use of low-value care. Nearly half of Americans with employer-provided insurance were required to meet an individual deductible of more than $1,000 in 2015, and many plans go much higher, with deductibles in the $5,000-$6,500 range.1

There’s just one problem – we have little evidence to suggest that these high-deductible plan designs work. To control spending and bring better value to our healthcare system, we need a new vision for what the consumer’s role should be.

The Theory Behind Consumer-Directed Healthcare and High-Deductible Plans

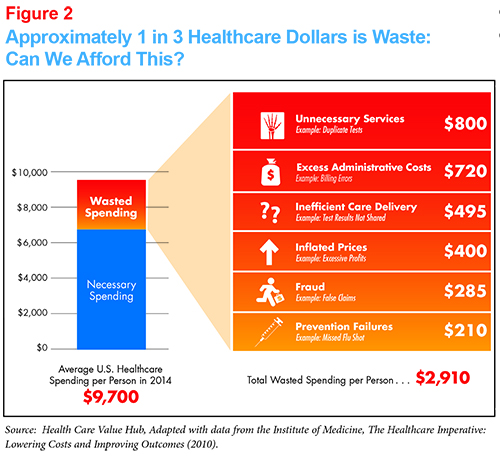

Whether described as a high-deductible health plan or consumer-directed healthcare--either paired with a tax advantaged account like an HRA or an HSA2 or not--the theory is the same: If consumers face the consequences of their health spending they will spend their dollars more wisely. With up to 30 percent of healthcare spending classified as “waste” by the Institute of Medicine,3 the goal is for consumers to cut out unnecessary or “wasteful” spending and put downward pressure on prices.

Even When These Plans Save Money, It's Not Because Enrollees Become Wise Shoppers

High-deductible health plans have been associated with lower premiums (compared to plans featuring lower consumer cost sharing) leading some to suggest they work as intended. But much of these premium reductions can be attributed to factors that don’t have to do with wiser spending by enrollees:

- Raising cost sharing, all other things being equal, will lower premiums because a smaller portion of medical spending is being paid by the health plan. In essence, some of the spending has been shifted to enrollees.

- In their early years, these plans attracted healthier-than-average participants.4 The lower-than-average-healthcare needs of these enrollees lead to lower premiums regardless of the cost-sharing benefit design.

- Enrollees do spend less when faced with higher cost sharing – the evidence is quite clear on this – but they don’t necessarily spend more wisely.

A 2013 RAND study found little evidence that consumers engage in more price shopping when faced with higher cost sharing.5 The findings also showed that participants in high-deductible plans use less of both low- and high-value services. Particularly concerning was the reduction in the use of free preventive services.6 Another recent study leveraged a natural experiment that occurred at a large self-insured firm which required all of its employees to switch from an insurance plan that covered all health costs to a high-deductible plan.7 The study found that the company indeed saved money, but that all the savings were due to employees reducing their use of healthcare services --none of the savings were due to price shopping or quantity substitutions. As with earlier studies, both low- and high-value care were reduced. Moreover, the sickest workers were the most likely to reduce their use of care while still under the deductible — even though this group is most likely to reach their deductible by the end of the year and thus should have less incentive to curtail spending (in theory).

Why High-Deductible Plans Don’t Address Health Care Spending Growth

Several studies point to why consumers don’t become wise shoppers when confronted by increased cost sharing: because it isn’t easy and information is lacking for where to go for a good outcome. Consumers can’t be expected to distinguish low-value from high-value care if evidence is not available. This is hard for almost all stakeholders in healthcare. There are several reasons:

- A surprising amount of care hasn’t been labeled as high value or low value. The Institute of Medicine estimates that more than half of the treatments delivered today are without clear evidence of effectiveness.8 And defining “value” is a complex task, fraught with judgments, such as “value to whom.” The Choosing Wisely campaign is one of a few exceptions.9

- Prices are hidden. Consumers rarely know the price of health services and providers, who often are unable to help consumers when they seek price information. A 2012 study found that only 26 percent of internal medicine residents knew how to find the costs of tests and treatments.10 In another study, a mystery shopper contacted hospitals for the price of an MRI. The “patient” was transferred three to seven times and when finally put in contact with the correct person they often had to leave a message and wait five to seven days to get a realistic answer to what seems to be a straightforward question.11 In addition, to date, consumer use of payer provided pricing tools has been very low.12 Once a price is found, t there is the additional hurdle of determining an enrollee’s share of these prices. Out-of-pocket costs are dependent on the consumer’s particular insurance policy design and whether the service will be delivered in- or out-of-network.

- Consumers have limited access to usable quality information. The reasons range from the dearth of comparative effectiveness research to the fact that we rarely provide usable quality information at the provider/service level. Given well-documented variation in quality, it is essential that consumers not shop on price alone.13 While consumers may be tempted to let price (if known), or even provider reputation, stand in as a substitute for quality, study after study shows that price is unrelated to quality.14

- Consumers don’t view healthcare as a commodity. Many consumers do not view doctors, hospitals and treatments as commodities and, as such, think price should not be a factor in making healthcare decisions. Instead, consumers believe healthcare decisions should be based on health need and what their providers recommend, rather than the price tag.15

- Shopping can’t address all forms of waste. Given that waste in our system can take many forms--for example, prices that are too high and high administrative costs (Exhibit 2), we need to be careful not to lump in forms of waste can be readily detected or addressed while “shopping.”

High-Deductible Health Plans Are a Consumer Hardship

In addition to the fact that high-deductible plans don’t work as intended, the evidence shows far too much consumer harm from unaffordable cost sharing.

Myriad surveys have found that 30 percent of consumers struggle to afford the care they need.16 And this is not just due being uninsured. The Commonwealth Fund has found that the share of working-age adults who had health insurance all year but were underinsured has been rising since 2003, hovering around 22 percent during the past several year.17 To be underinsured means to not have the financial resources to meet the cost-sharing obligations of your health plan in the event of a serious illness or injury.

The stories are heartbreaking. When they can’t afford care, patients report:

- Cutting back on care. They split pills or do not fill a prescription. They put off calling the doctor. The result can mean suffering pain, larger bills down the road or permanent disability.18

- Cutting back on other critical purchases like rent, groceries or other necessities in order to afford medicines or care.19

- Couples divorcing in order to qualify for Medicaid or putting off plans to have a baby.20

- Filing for bankruptcy. Medical debt is the single largest cause of consumer bankruptcy--outpacing bankruptcies due to credit-card bills or unpaid mortgages.21

Consumers also suffer from the stress and anxiety about making these tradeoffs. It's no wonder that affording healthcare is a top concern for Americans.22

Rethinking Benefit Design to be Consumer Friendly

It's time to remove any implication that “consumer-driven health care” is consumer friendly. Instead, we need to emphasize alternate health plan designs that are truly consumer-centric and evidence-based.

To make benefit design truly consumer-centric, health benefit designs should:

- Feature affordable cost sharing. For example, exempting key services from the deductible (if any), such as a fixed number of primary care visits, incentivizes even those with limited means to get needed care rather than allowing a condition to worsen and become big-ticket expenditures. And cost sharing may need to slide with income, as some large employers are doing.

- Provide usable information about what is high-value and low-value care. Ideally, low-value care wouldn’t even be offered by providers and provider networks would be constructed so that consumers could not take a misstep in their selection of provider. But current measurement methods and our dismal state of comparative effectiveness research23 make it difficult to fully realize this aspirational vision. As an interim measure, plan design features like reference pricing and value-based insurance design can help steer consumers to high-value care, if implemented in an evidence-based and consumer-friendly way.24Consumers may prefer not to shop based on price but they are very likely to choose the treatment option and provider that results in the best outcome from them--if they can figure out what that is!

- Feature high value provider networks. If health plans can identify providers with a track record of high-value care, consumers can have confidence in their shared approach to selecting treatment options.

- Spur providers, hospitals, drug manufacturers and medical device makers to address high healthcare costs. We need to cut out unnecessary care but also bring down healthcare prices.

Reducing Spending Through Provider-Directed Interventions

Because Americans struggle to afford both their premiums and high out-of-pocket (OOP) costs, it is imperative that we step up our efforts to address the underlying cost of medical care. But there’s little evidence that consumers should be the primary target of efforts to change which medical services we consume and how they are priced.

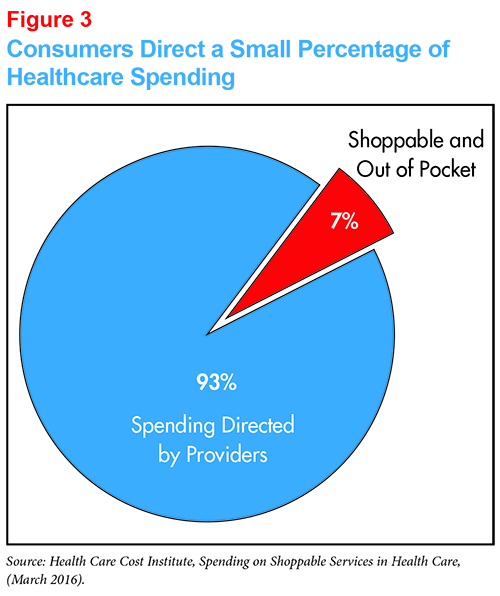

Consumers direct only a small amount of healthcare spending. The amount of spending that is both shoppable (non-urgent) and paid out-of-pocket represents just 7 percent of our overall private health insurance spending--and that’s an upper bound.25 Several studies that have looked at the impact of high-deductible health plans have found that the major effect is the consumer’s decision about whether or not to initiate treatment. Once treatment is initiated, even if paying OOP, consumers often allow the provider to direct their care.26 When one takes into account the dearth of usable shopping tools, and the fact that providers are still directing much of our shoppable care, the proportion directed by consumers is likely less than 7 percent.

Providers direct the vast majority of our spending. Physicians order diagnostic tests, recommend treatment options and make referrals. They advise Medicare on what physician payments should be, which in turn flows throughout the healthcare system.27 Along with doctors, hospitals, drug manufacturers and device manufacturers must be the focus of efforts to reducing health spending and extract more value from our health system.

To start, providers must take on the role of being stewards for the patient’s healthcare dollar.28 While providers also suffer from lack of useable data on prices and sometimes even the quality of their fellow practitioners, they are much better positioned and trained to help consumers make high-value healthcare decisions. A rapid timeline must be established to add this obligation to their code of ethics and provide the tools that make it reasonable to comply with the requirement.29

Further, our approach to controlling out-of-control prices must emphasize the use of evidence-based, provider-targeted strategies to control costs and incentivize high-value care. These approaches include provider payment reforms that group care into treatment bundles and pay for value as opposed to volume. Improved tracking of spending flows, including provider-specific detail, will be critical to these efforts and drug and device manufacturers bear similar scrutiny.30 Legislators, regulators, health plans and larger payers must double their efforts to address healthcare prices that exhibit unjustified variation within a geographic area, unjustified year-over-year growth or are widely out of line with the consumer benefit received.

These efforts must be accompanied by additional investment in true comparative effectiveness research to improve our understanding of what is high-value care and low-value care. In the absence of this information, neither consumer cost sharing nor provider payment reform will be capable of better directing our spending.

Consumers Deserve Actionable Information on Prices and Quality

Keeping the evidence about how consumers approach healthcare choices firmly in mind, the foregoing discussion does not eliminate the need to provide reliable, timely, actionable information about prices and quality to consumers.

Why? While consumers direct a relatively small share of total health spending (7%), that share looms large in terms of their personal spending. Shoppable services make up, on average, 65 percent of total OOP spending.31 Consumers who wish to shop should be able to do so with confidence. They should have reliable, timely, information on the prices and quality of their doctors, hospitals and treatments choices to keep them safer, informed and more financially secure when consuming healthcare and buying health insurance. This information should include information about what a fair price would be and relative efficacy of treatment alternatives.32 As described above, the information being provided today is too often either incomplete, hard to find, not actionable or unreliable. As with providers, a rapid timeline must be established to make information available to consumers that hits all these markers, starting with shoppable services.

By providing reliable information about outcomes and by arming consumers and providers with the same information, we enable consumers to engage with the healthcare system with their informed voice, rather than with their dollars. While the ability to make decisions based on quality information may move the market in a desirable direction,33 the main reason to provide this information is because it is just and fair.

Conclusion

Consumers should not have to bear the brunt of poorly functioning healthcare markets that don’t deliver value. The Institute of Medicine estimates that one third of what we spend is wasted--it does not result in better health outcomes. That means consumers are paying too much. We don’t have to settle for high and rising premiums and increasing burden of out-of-pocket costs because there are many other promising approaches available to us. Health plans, providers, drug manufacturers, device makers, regulators and policymakers must all work together to lower the underlying cost of healthcare.

Notes

1. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015 Employer Health Benefits Survey (Sept. 22, 2015). http://kff.org/health-costs/report/2015-employer-health-benefits-survey/

2. For background on these designs, see: Healthcare Value Hub, High-Deductible Health Plans—A Strategy Not Appropriate for Many Consumers, Research brief No. 3, Washington, D.C. (MARCH 2015).

3. Institute of Medicine, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America (September 2012).

4. RAND, Analysis of High Deductible Health Plans, (2011). http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR562z4/analysis-of-high-deductible-health-plans.html

5. Sood, Neeraj, et al., Price Shopping in Consumer-Directed Health Plans, RAND, Washington D.C. (March 2013).

6. Ibid. Also: Reed, Mary E., et al., “In Consumer-Directed Health Plans, A Majority of Patients Were Unaware of Free or Low-Cost Preventive Care,” Health Affairs, Vol. 31, No. 12 (December 2012).

7. Brot-Goldber, Zarek, et al.,What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics, National Bureau of Economic Research,Cambridge, Mass., (November 2015).

http://www.nber.org/papers/w21632?utm_campaign=ntw&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ntw

8. Institutes of Medicine, Learning What Works: Infrastructure Required for Comparative Effectiveness Research: Workshop Summary (2007). Similarly, Clinical Evidence, a project of BMJ, combed through the 3,000 medical treatments that have been studied in controlled, randomized studies. They found, for half of those, we have no idea how well they work.

9. Choosing Wisely is an initiative of the ABIM Foundation that promotes patient-physician conversations about unnecessary medical tests and procedures. Consumer Reports is a partner in this campaign.

10. Rappleye, Emily, “Only 1 in 4 of internal medicine residents know where to find costs of care,” Beckers Hospital Review (June 25, 2015).

11. Gamble, Molly,“Only 1 in 4 of Internal Medicine Residents Know Where to Find Costs of Care,” Beckers Hospital Review (June 24, 2015).

12. Based on a national survey of health plans, Catalyst for Payment Reform found that while 98 percent of responding plans said they offer a cost calculator tool, just two percent of their patient members use these tools. Catalyst for Payment Reform, National Scorecard on Payment Reform (2013). http://www.catalyzepaymentreform.org/images/documents/NationalScorecard.pdf

13. Sarah Kliff, “I Thought People Should Shop More for Health Care. Then I Actually Tried It,” Vox (Oct. 19, 2015).

http://www.vox.com/2015/10/19/9567991/health-care-shopping-mri

14. The Associated Press-NORC, Finding Quality Doctors: How Americans Evaluate Provider Quality in the United States: Research Highlights (2014). http://www.apnorc.org/projects/Pages/HTML%20Reports/finding-quality-doctors.aspx

15. Melecki, Sarah, Victoria Burack and Lynn Quincy, Consumer Attitudes Toward Health Care Costs, Value and System Reforms: A Review of the Literature, Consumers Union (October 2014).

16. Consumer Reports, Health Consumer Experiences with Health Care Costs (2014). http://www.consumerreports.org/content/dam/cro/news_articles/health/PDFs/CRO_Health_Consumer_Experiences_Health_Care_Costs_10-14.pdf See also: Kaiser Family Foundation, Key Facts about the Uninsured Population ( October 2015); Kaiser Family Foundation, Problems Paying Medical Bills Among Low-and Middle- Income Non Elderly Adults, By insurance coverage in Fall 2014 (2014); The Commonwealth Fund, New 11-Country Health Care Survey: U.S. Adults Spend Most; Forgo Care Due to Costs, Struggle to Pay Medical Bills, and Contend with Insurance Complexity at Highest Rates ( November 2013); and Riffkin, Rebecca, Cost Still a Barrier Between Americans and Medical Care, Gallup, Washington, D.C., (November 2014).

17. The Commonwealth Fund, The Problem of Underinsurance and How Rising Deductibles Will Make It Worse, Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, (2014). http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/may/problem-of-underinsurance

18. Ibid.

19. Brodie, Mollyann, et al., The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey, Kaiser Family Foundation, (Jan. 5, 2016).http://kff.org/health-costs/report/the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundationnew-york-times-medical-bills-survey/

20. Ibid.

21. Unfortunately, there is no commonly accepted measure for when medical debt can be considered the primary cause of the bankruptcy. But myriad studies have found that medical debt plays a leading role. Estimates range from 62% to 26% of consumer bankruptcy filings. See: Daniel A. Austin, “Medical Debt as a Cause of Consumer Bankruptcy,” Maine Law Review, Vol. 67, No. 1 (2014) and LaMontagne, Christina, “NerdWallet Health Finds Medical Bankruptcy Accounts for Majority of Personal Bankruptcies,” NerdWallet Health (June 19, 2013).https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/health/managing-medical-bills/nerdwallet-health-study-estimates-56-million-americans-65-struggle-medical-bills-2013/

22. Jost, Timothy, “Affordabiliy, the Most Urgent Health Reform Issue for Ordinary Americans,” Health Affairs Blog (Feb. 29, 2016). http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/02/29/affordability-the-most-urgent-health-reform-issue-for-ordinary-americans

23. “Surprise! We Don’t Know if Half Our Medical Treatments Work,” Washington Post (Jan. 24, 2013).

24. Consumers Union, Creating a Consumer Friendly Reference Pricing Program (Aug. 1, 2014).

http://consumersunion.org/research/creating-a-consumer-friendly-reference-pricing-program/

25. Health Care Cost Institute, Spending on Shoppable Services in Health Care (March 2016). See also:

Frost, Amanda, David Newman and Lynn Quincy, “Health Care Consumerism: Can The Tail Wag the Dog?” Health Affairs Blog (March 2, 2016). http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/03/02/health-care-consumerism-can-the-tail-wag-the-dog-2/

26. Health Affairs, Health Policy Brief: Patient Engagement (February 2013).

27. The Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) involves both the AMA and the national medical specialty societies. It serves as a panel to develop recommendations to CMS regarding the value of physician services under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

28. In 2012, the AMA did add an obligation take cost into consideration when there are options for the best way to treat a patient to its code of medical ethics. The study committee found that physicians and medical students need training to learn about health care costs and how their decision-making can affect overall health spending. http://www.amednews.com/article/20120702/opinion/307029946/4/

29. Shah, Neel, Physician's’ Role in Protecting Patients’ Financial Well-Being, American Medical Association (February 2013).

http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2013/02/msoc1-1302.html

30. For more information on fair prices, see our forthcoming issue brief: The Case for Price Transparency in Health Care (May 2016).

31. Ibid.

32. A lits of provider-targeted strategies can be found at the Healthcare Value Hub website: https://healthcarevaluehub.org/improving-value/who-target/

33. Russell, Katie, et al., “Charge Awareness Affects Treatment Choice: Prospective Randomized Trial in Pediatric Appendectomy,” Annals of Surgery (July 2015).