Rx Costs: A Primer for Healthcare Advocates

After a decade of relative stability as increasing use of generics significantly moderated spending, drug costs are set to increase dramatically over the coming years. Increased reliance on high-cost specialty drugs and an expected reduction in savings derived from generics will significantly increase overall drug spending and drive up premiums and cost sharing for consumers.

Of greatest concern, the price of new specialty drugs is truly prohibitive. Twelve of 13 cancer drugs approved by the FDA in 2012 were priced over $100,000 per course of treatment.1 The term “specialty drug” does not have a uniform definition. The term broadly comprises drugs that are: high priced; often (but not always) made of biological matter; treat complex conditions; require special handling; or require infusion or injection in a doctor’s office. Increasingly, specialty drugs are specifically tailored to subpopulations.2

Consider the impact of new drugs for hepatitis C on state Medicaid budgets. Sovaldi—considered a genuine medical breakthrough—is priced at $84,000 for a full treatment, or $1,000 per pill. Harvoni, a successor combination therapy for hepatitis C treatment, is priced at $94,500 for a full course of treatment.3

States are projected to spend more than $55 billion if they provide all Medicaid patients with hepatitis C the latest therapy regimen of Sovaldi.4 To put this into perspective, total state Medicaid spending for acute care was approximately$ 275 billion in 2012.5 So that means projected spending on only one drug is 20 percent of the cost of the combined Medicaid spending by states on all acute care service services for 2012.6 These prices are simply unsustainable for our healthcare system.

In response to high drug prices, payers are increasingly relying on strategies with negative consequences for consumers, such as shifting costs to patients who need these drugs, designing plans to discourage sicker individuals from enrolling and limiting access to these drugs. Medicaid programs in thirty-five states require prior authorization for Sovaldi and several states require treatment candidates to meet a set of clinical or clinical-related criteria for prior authorization. Many states further require candidates to undergo testing to determine the severity of their disease before they are permitted to receive treatment with Sovaldi. At least seven states limit duration, frequency or quantity of the drug. For example, Arizona has a “once in a lifetime treatment” rule allowing Medicaid recipients only one opportunity to receive the drug.7

This primer will address the reasons for the trend toward higher price drugs, why generic drugs won’t moderate spending as much as in the past, and some of the long-term solutions that will be needed to control costs in the future.

Reasons for Recent Uptick in Drug Spending

Spurred by patent expirations of blockbuster drugs like Lipitor and Plavix and increased use of generics, the drug spending trend had moderated in the last decade8—particularly when compared to the double-digit growth seen in the 1990s. For example, between 2011 and 2012, drug spending grew just 0.4 percent.9 Contributing to this low trend, the share of prescriptions that were generic increased to nearly 78 percent in 2012, an 8 point increase over the previous year.10

Two important trends are bringing this period of low drug spending growth to an end: increased spending on prescription drugs, and the diminishing cost-saving impact of generic drugs. But in 2013, drug spending rose 2.5 percent, spurred by an increase in specialty drug spending.11 Overall drug spending is projected to climb to by 6 percent per year from 2016 to 2019.12 More recent data suggest that a spike in the cost of compounded drugs13 is contributing to a hike in drug prices, but this a recent phenomenon. It remains to be seen whether this is a long-term trend or whether payers will be able to successfully manage the use of compounded drugs.14

Increased Spending on Specialty Drugs

Pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts reports that drug spending for its clients in 2014 was driven largely by an unprecedented 30.9% increase in spending on specialty medications.15

Specialty drugs are used by fewer than 1 percent of privately insured patients in the United States. However, these drugs currently account for more than 25 percent of all drug spending.16

What’s more, specialty drug spending is projected to account for an astounding 50 percent of total drug spending by 2020.17

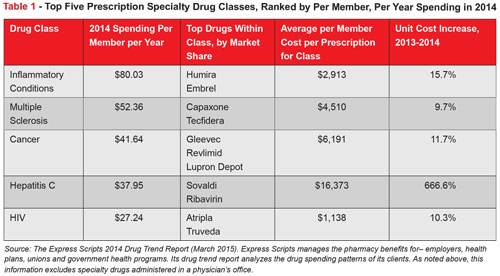

Many, but not all, specialty drugs are biologics (an exception is high-priced Sovaldi, which is a traditional pill). As the name implies, biologics are made of biological matter. They are often referred to as “large molecule” products because of the greater complexity of their molecular structure compared to “small molecule” traditional drugs. Biologics include drugs to treat cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis (See Table 1).18 On average, biologic drugs are 22 times more expensive than typical brand name drugs. Research by PhRMA, the leading advocacy organization for the pharmaceutical industry, suggests that some 900 biologics are under development.19 Biologics are projected to outpace traditional, non-biologic drug spending and are expected to represent approximately 20 percent of total global pharmaceutical market value by 2017.

And these reports likely understate growth in specialty drug spending. Approximately half of specialty drug spending is billed through the medical benefit, not the pharmacy benefit and thus is not reflected in many common sources that report prescription drug spending, like the Express Scripts Drug Trend Report.20 This is because many specialty drugs are infused or injected in physician offices.

Prescription drugs administered in a physician setting are often inflated through physician “buy and bill” practices, effectively a mark-up over the drug’s price. Because specialty drugs are often bundled with other services it can be difficult to attain a comprehensive understanding of underlying cost trends.

Generics Will be Less Effective in Bringing Down Costs in the Future

High rates of generic substitution will continue, but will do less and less to bring down overall spending. In coming years as the market value of products expected to go off patent are significantly less than some of the blockbusters that went off patent in 2012. While generic dispensing rates are expected to remain high, a leading retail pharmacy and pharmacy benefits manager, CVS/Caremark, expects that the moderating influence of generics will wane as non-generic spending grows to represent more of the spending total.21

Increases in Generic Costs on the Horizon

A second reason generics are less likely to moderate future spending is that the prices of many generic drugs are increasing. The reason for these generic cost increases are complex and due to many factors, including raw material shortages and generic competitors leaving the market. Whatever the reason, many drugs that have been historically inexpensive—such as Tetracycline (antibiotic) and Digoxin (heart medication)—have seen sharp price increases. One analysis found that half of all retail generic drugs became more expensive from mid-2013 to mid-2014. Some generic drug prices have increased 10 fold during this period.22

Another reason is because more of these “generic” alternatives will take the form of biosimilars, which are essentially a generic for a biologic drug. They are called biosimilars because biologics can’t be made exactly the same way as traditional drugs. FDA recently approved Zarxio, the first biosimilar for Neupogen, a drug used to prevent infections for cancer patients. But experience thus far from Europe, which has a head start on approving biosimilars, indicates that they can be made safely.

Historically, having two generic competitors for drugs can lower the average generic price to nearly half the price of the brand product. If an even larger number of generic competitors enter the market the price can fall to 20 percent of the price of the brand product.23

However, biosimilars are not likely to drive down drug costs as much as typical drugs based on experience from the European Union, which has approved biosimilars since 2009. Research showed price reduction of 10-25 percent.24 As the biosimilar market improves and consumers and providers become more comfortable with their use, greater price reductions may be possible. But for the near term, analysts do not expect biosimilars to impact prices to the same degree as traditional generic drugs.

Impact on Consumers

High drug costs can have an impact on consumers in a number of ways.

High out-of-pocket costs

Though the Affordable Care Act provides some protection from high drug costs through a maximum cap on out-of-pocket costs, the cap is still quite high for most consumers. In 2015, the out-of-pocket maximum is $6,600 per year for an individual and $13,200 for a family.25

In practice this means enrollees with serious illnesses might hit the ACA’s out-of-pocket limit in a matter of weeks, just for drugs. For example, enrollees with HIV in some health plans paid an average of $4,892 out of pocket for their medications.26 Research indicates high costs can negatively impact adherence.27

Discriminatory Design

Private insurers have been moving to three- and four-tier formularies where consumers are charged lower co-insurance or co-pays for generic drugs and significantly more for drugs in the highest tier. The theory is that tiering helps guide consumers to lower cost, equally efficacious alternative medications by offering lower cost sharing.

But the movement toward tiers has a downside. Recent data suggests that insurers are using pharmacy benefit design to discourage sicker enrollees from enrolling in their health plans. Plans are creating formulary tiering structures that place all drugs—including generics—for certain conditions, such as HIV, in the highest cost formulary tiers. In some cases, there is no medically appropriate alternative medication. In one study, researchers found evidence of this “adverse tiering” in 12 of the 48 plans reviewed.28

Other research shows that this type of discriminatory design is being used to target other high-cost conditions such as mental illness, cancer, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. One study showed that 41 percent of Marketplace exchange Silver plans required at least 30% co-insurance for all covered drugs in at least one class.29 Fifty-one percent of plans put all drugs for one serious illness (including generics) in the highest cost tier. In other words, over half of Marketplace plans did not make a lower cost sharing option available for drugs for one high-cost condition.30

This type of discriminatory design is problematic on two levels. First, it creates potential for unexpected expenses as enrollees who choose a plan for low premiums may be surprised with high out–of-pocket costs. And Consumers Union research shows that consumers often have a difficult time understanding their health insurance. They may not understand, for example, the difference between coinsurance and copays and may not understand what a specialty drug is and end up getting hit with unexpected high drug costs at the very time they are coming to terms with a newly diagnosed serious illness.3131 Secondly, over time, the use of these types of designs will result in adverse risk selection, driving up premiums in plans that attract sicker enrollees.

Limited Patient Choice

Another market response to high costs is to limit patient choice. For example, the nation’s largest pharmacy benefits manager, Express Scripts, negotiated an exclusive deal with AbbVie, Inc., the manufacturer of an alternative to Sovaldi, in exchange for a discounted price. But there are differences in how the drugs are taken that might have an impact on adherence. There may also be other patient characteristics that might make a particular drug more appropriate than its competitor. Depending upon state law on medical necessity, consumers in plans that use Express Scripts to manage their drug benefit will not be able to get reimbursement for Sovaldi, if that is the drug their doctor feels is best for them.

Further, as discussed above, public insurers such as Medicaid may be forced to limit access to drugs due to their high cost.

Higher Premiums

Finally, the portion of high drug costs paid by insurers is ultimately passed on to consumers in the form of higher premiums, making insurance harder to afford.

Options for Curtailing Rx Costs

1. Reforming the Way Monopolies are Granted to Drug Companies

Patent Reform

When a drug is covered under patent protection, only the pharmaceutical company that holds the patent is allowed to manufacture, market the drug and eventually make profit from it. Once the patent has expired, the drug can be manufactured and sold by other companies. Patents give drug manufacturers a monopoly allowing them to reap steep financial rewards for successful drugs during the patent term. Average profits for brand-name pharmaceutical companies is 18.4 percent compared to 5.6 percent for generics.32

Ultimately, long-term solutions to drug prices will require federal action on patent terms. Patent terms must be reasonable and patents must be granted only for real advances rather than minor tweaks or reformulations of existing drugs. Limiting the monopoly period that drug companies enjoy speeds up competition that can drive prices down.

FDA Reform

Gaining exclusivity is another way, outside the patent system, for brand drugs to gain effective monopolies. Exclusivity is a concept related to the FDA approval processes and refers to a period of time when the FDA will not approve a generic competitor. Exclusivity periods are distinct from patent terms.

FDA exclusivity periods need to be granted sparingly and limited to where needed to encourage actual innovation. There are certain exclusivity periods, such as the exclusivity period for biologics that are so long they will delay generic entry, keeping costs high. Under current law, the exclusivity period for biologics is 12 years. Many advocates believe a seven year period would be more appropriate to stimulate innovation without driving up costs to unaffordable levels.

2. Greater Government Oversight Over Pricing

Many countries directly control the price of drugs. In limited ways, the U.S. government does intervene to control drug prices. For example, the Medicaid program requires manufacturers to provide a rebate back to the program. Examples of methods of government price controls that could be used to restrain drug costs include:

- Allowing the Medicare program to directly negotiate prices with manufacturers for the drugs used by seniors under the pharmacy benefit known as Medicare Part D. With its great bargaining power, researchers believe that this could reduce prices.

- Granting compulsory licenses to a third party. Compulsory licensing is when a government allows a generic company to produce the patented product or process without the permission of the patent owner. This is often done by governments of developing countries to bypass patent laws that make drugs unaffordable for their citizens.

3. Increased Use of Comparative Effectiveness Research

Right now the standard for FDA approval is that a drug works better than a placebo, however marginally. To lower costs without harming consumers, we must stop approving drugs that aren’t effective or better than lower cost alternatives (including non-pharmaceutical options).

And we must follow up with drugs once they come to market. Often drugs come to market and extract a high price because initial impressions of the drugs are favorable. But payers should adjust pricing after the drug hits the market to make sure a drug that commands high prices upon initial introduction are still worth paying high prices for as clinicians gain more experience with the drug. For example, the breast cancer drug Avastin was initially considered very promising but ultimately didn’t live up to the efficacy claims its manufacturer made about treating breast cancer after it was introduced.33

4. Generic-Friendly State Substitution Laws

While mostly governed by federal law, state laws do impact drug costs. State substitution laws allow pharmacists to substitute generic drugs for brand drugs. States with more generic-friendly substitution laws have higher generic use.34 As biosimilars become more available, making sure they can be substituted for the brand biologic will be an important way to keep costs down for these expensive drugs.

Conclusion

Enacting the reforms necessary to drive down drug costs is a difficult proposition.

But if current trends continue, high drug costs will impact both overall healthcare spending and consumers’ out-of-pocket spending, with negative consequences for access to drugs due to affordability.

It will take a sustained effort by consumers, payers, purchasers working at both the state and federal level to make headway on these issues. If healthcare costs are to be sustainable, and if access to life-saving drugs is to be preserved, advocates and others will have no choice but to take on a powerful industry head on. In the meantime, advocates may want to consider getting involved in benefit design rules being discussed in state exchanges to try to mitigate the impact of high drug costs on sicker enrollees.

Notes

1. Light, Donald W., and Hagop Kantarjian, “Market Spiral Pricing of Cancer Drugs,” Cancer (Nov. 15, 2014). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.28321/epdf

2. Express Scripts, The Express Scripts 2014 Drug Trend Report (March 2015). http://lab.express-scripts.com/drug-trend-report

3. Pollack, Andrew, “Hepatitis C Treatment Wins Approval, but Price Relief May Be Limited,” The New York Times (Dec 19, 2014).

4. Express Scripts, State Governments May Spend $55 Billion on Hepatitis C Medications (July 17, 2014). See more at: http://lab.express-scripts.com/insights/specialty-medications/state-governments-may-spend-$55-billion-on-hepatitis-c-medications#sthash.bobcQLD0.dpuf and http://lab.express-scripts.com/insights/specialty-medications/state-governments-may-spend-$55-billion-on-hepatitis-c-medications.

5. Acute care services included in this figure are: inpatient, physician, lab, X-ray, outpatient, clinic, prescription drugs, family planning, dental, vision, other practitioners' care, payments to managed care organizations, and payments to Medicare.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts: Distribution of Medicaid Spending by Service, http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-of-medicaid-spending-by-service/#

7. Medicaid Health Plans of America, Coverage Restrictions in State Medicaid Programs (Sept. 29, 2014). http://www.mhpa.org/_upload/SovaldiSqueeze-Oct2014.pdf

8. Martin, Anne B., et al., “National Health Spending in 2012: Rate of Health Spending Growth Remained Low for the Fourth Consecutive Year,” Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No.1 (January 2013).

9. National Health Expenditure Data, Aggregate and Per Capital Amounts and Percent Distribution, by Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1960-2012.

10. Martin, Anne B., et al. (January 2013).

11. National Health Expenditure Data, 2013 Fact Sheet, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.html

12. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Projections 2013-2023, Forecast Summary, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/Proj2013.pdf

13. Compounded drugs are customized medications that meet specific needs of individual patients and are produced in response to a licensed practitioner’s prescription. Compounded drugs are not FDA approved. Compounded drugs are generally produced by a licensed pharmacist, a licensed physician who can work at a pharmacy, a hospital or a specialized outsource facility.

14. Express Scripts, 2014 Drug Trend Report, http://lab.express-scripts.com/drug-trend-report

15. Ibid.

16. Starner, Catherine I., and Caleb G. Alexander, “Specialty Drug Coupons Lower Out-of-Pocket Costs and May Improve Adherence at the Risk of Increasing Premiums,” Health Affairs, Vol. 33, No. 10 (October 2014).

17. Johnson, et al., “Specialty Drugs are Forecasted to be 50 Percent of All Drug Expenditures in 2018,” Prime Therapeutics, Eagan, Minn.

18. Biological products, or biologics, are medical products made from a variety of natural sources (human, animal or microorganism). Examples of biological products include vaccines and many cancer treatments.

19. Purvis, Leigh, A., Sense of Déjà vu: The Debate Surrounding Sate Biosimilar Substitution Laws, AARP (September 2103).

20. The Express Scripts, 2014 Drug Trend Report (April 2014).

21. CVS/Caremark, Insights 2014. http://investors.cvshealth.com/~/media/Files/C/CVS-IR/reports/2014-cvs-caremark-insights-report.pdf

22. Drug Channels, Retail Generic Drug Inflation Reaches New Heights (Aug. 14, 2014).

http://www.drugchannels.net/2014/08/retail-generic-drug-inflation-reaches.html

23. Food and Drug Administration, Generic Competition and Drug Prices, http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm129385.htm

24. Guy, Roland, Modeling Federal Cost Savings of Follow-on Biologics, Avalere Health (March 2007). http://www.avalerehealth.net/research/docs/Follow_on_Biologic_Modeling_Framework.pdf

25. Note that this limit does not include other costs that consumers have to pay such as premium costs, balance billing amounts for non-network providers and other out-of-network cost-sharing, or spending for non-essential health benefits. https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/out-of-pocket-maximum-limit/

26. Jacobs, Douglas B., and Benjamin D. Sommers, “Using Drugs to Discriminate—Adverse Selection in the Insurance Marketplace,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 372 (2015). http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1411376

27. Starner (October 2014).

28. Jacobs (2015).

29. Approximately two-thirds of exchange enrollees picked Silver plans in 2014.

30. Avalere Health, Exchange Plans Increase Costs of Specialty Drugs for Patients in 2015, http://avalere.com/news/exchange-plans-increase-costs-of-specialty-drugs-for-patients-in-2015

31. Quincy, Lynn, What's Behind the Door: Consumers' Difficulties Selecting Health Plans, Consumers Union (January 2012).

32. Wright, Tiffany C., The Average Profit Margin of Pharmaceuticals, Demand Media, http://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/average-profit-margin-pharmaceuticals-20671.html

33. Food and Drug Administration, Press Release (Nov. 18, 2011). http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm280536.htm

34. Purvis (September 2013).