Social Determinants of Health: Food Insecurity in the United States

Defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play. These factors profoundly influence the health of individuals and communities in the United States.1

Among the various social determinants of health, food insecurity has one of the most extensive impacts on the overall health of individuals. The U.S. Department of Agriculture found that food insecurity affects 11 percent of U.S. households.2 Moreover, individuals who are food insecure are disproportionally affected by chronic diseases, including diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity, which exacerbates adverse effects on overall health and wellbeing.3

This research brief explores the linkages between food insecurity, overall health and health care costs, and examines the pathways policymakers and healthcare providers can use to increase access to nutritious food.

What Does It Mean To Be Food Insecure?

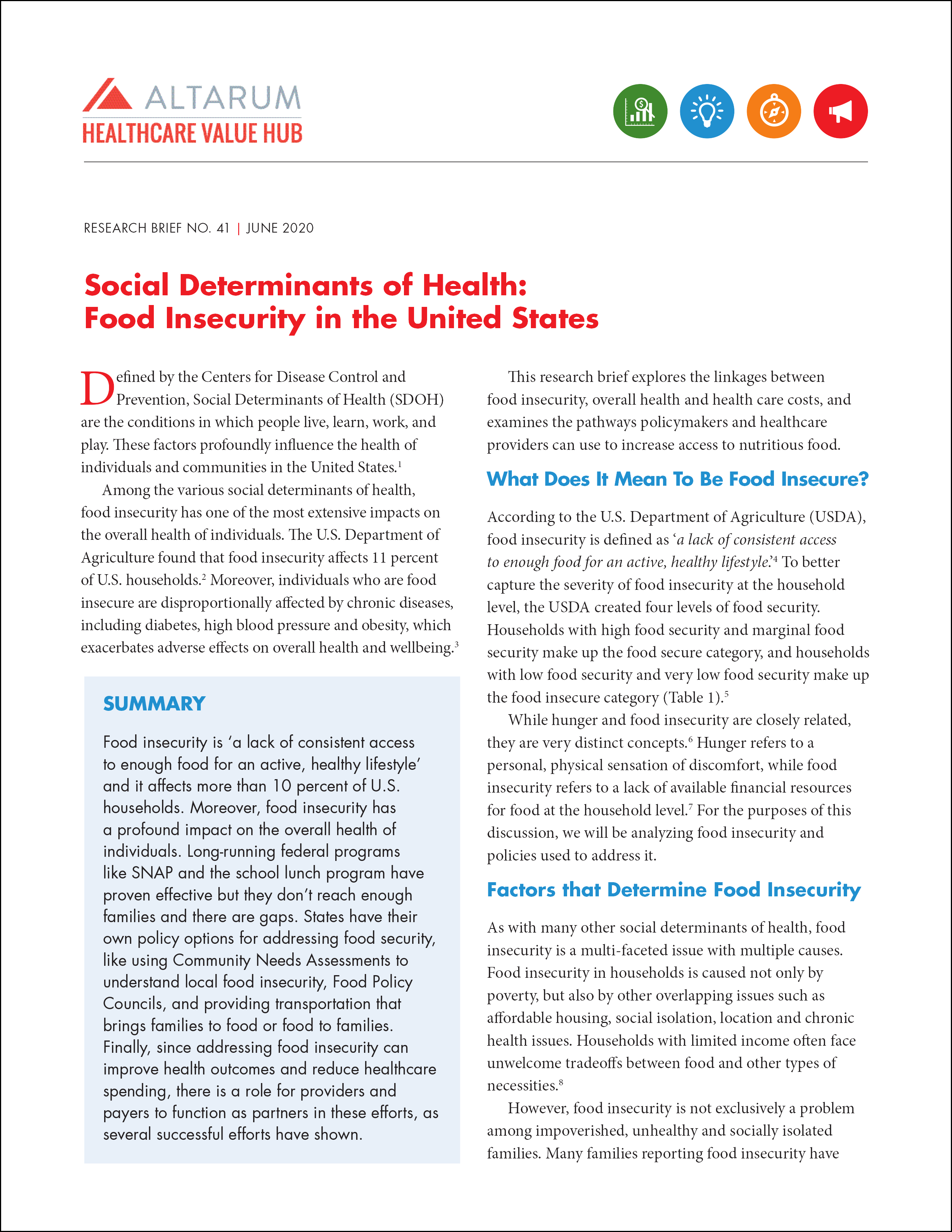

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), food insecurity is defined as ‘a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy lifestyle.’4 To better capture the severity of food insecurity at the household level, the USDA created four levels of food security. Households with high food security and marginal food security make up the food secure category, and households with low food security and very low food security make up the food insecure category (Table 1).5

While hunger and food insecurity are closely related, they are very distinct concepts.6 Hunger refers to a personal, physical sensation of discomfort, while food insecurity refers to a lack of available financial resources for food at the household level.7 For the purposes of this discussion, we will be analyzing food insecurity and policies used to address it.

Factors that Determine Food Insecurity

As with many other social determinants of health, food insecurity is a multi-faceted issue with multiple causes. Food insecurity in households is caused not only by poverty, but also by other overlapping issues such as affordable housing, social isolation, location and chronic health issues. Households with limited income often face unwelcome tradeoffs between food and other types of necessities.8

However, food insecurity is not exclusively a problem among impoverished, unhealthy and socially isolated families. Many families reporting food insecurity have incomes above the official poverty line.9 Researchers have noted various reasons for this. First, food insecurity in relation to poverty level is typically based on current income, rather than looking at permanent income or income over a two-year period.10 Further, researchers and advocates note that food security status is influenced heavily by local area conditions such as high housing costs, high unemployment rates, residential instability, and high tax burdens.11

Access to healthy food can be a challenge for rural areas.12 Many rural areas lack retailers and stores that supply fresh, nutritious food, and are classified as food deserts.13 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define a food desert as an area that lacks access to affordable fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low fat milk and other foods that make up a healthy diet.14 In the United States, about 23.5 million urban and rural Americans live in a food desert, with nearly half of them in low-income areas.15 Moreover, the number of food deserts is likely under-reported, given that the North American Industry Classification System has determined that small corner stores, which primarily sell pre-packaged, unhealthy options, are in the same category as mainstream grocery stores selling a wide variety of healthy foods.16

Burden of Food Insecurity

Food insecurity affects about 11 percent of households in the U.S., where 1 in 8 adults and 1 in 6 children are in households that are food insecure.17 These households report not being able to afford balanced meals and worrying that food will run out before they have the money to buy more.18

Food insecurity across the U.S. is correlated with increased prevalence of chronic health conditions.19 In a 2018 study, researchers found that the most common chronic conditions for adults facing food insecurity were diabetes, hypertension and arthritis.20 Not surprisingly, these chronic conditions lead to higher healthcare costs and utilization. In the same study, researchers found that the adjusted annual incremental health care costs resulting from food insecurity among older adults were higher compared to those who did not experience food insecurity.21 As an example, one study shows diabetics that have limited access to food are at higher risk for hypoglycemic episodes, which can increase emergency department visits.22 Patients who experience food insecurity are nearly twice as likely to report such episodes.23

Overall, average healthcare costs for food-insecure adults were $1,834 higher than for food-secure adults—totaling $52.6 billion across all food-insecure households.24 These additional costs include all direct healthcare-generated costs, like clinic visits, hospitalizations and prescription medications.25

Federal Programs to Address Food Insecurity

It may come as a surprise to some that food insecurity is so prevalent today in light of long-running federal programs designed to alleviate the problem.26 In fact, levels of food insecurity are essentially unchanged since the federal government started collecting food security statistics in 1995.27 While federal efforts are having an impact on food insecurity, individuals and families are still struggling to put food on the table.

There are several federal programs designed to alleviate food insecurity. Formerly known as Food Stamps, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) serves as the first line of defense against hunger and food insecurity. SNAP participation has been shown to reduce food insecurity by 30 percent in some populations.28 Other studies show that SNAP benefits have positively impacted the overall health of children and reduced hunger.29 Moreover, SNAP experts note that, unlike Medicaid where there is a sharp cliff in terms of income eligibility, SNAP provides a sliding scale of support based on an individual’s income.30

However, more than one-quarter of people who are food insecure are not eligible for SNAP, leaving them with few options for healthy food.31 Reasons for ineligibility include immigration status, student status and being a childless adult who works more than 20 hours per week (regardless of income).32 Additionally, families are food insecure due to the fact they live in a food desert, but with incomes above the poverty level, would not be eligible for SNAP.

Food security could be increased by expanding eligibility for SNAP, increasing benefit amounts and by easing program access. Although states have modernized their use of online applications and implemented the use of call centers, barriers remain for individuals.33 In many rural areas, broadband access can impact the ability to apply for the SNAP program.34 To address these issues, the U.S. Food and Nutrition Service provides state agencies with a Program Access Review Guide for their SNAP programs, but the recommendations are voluntary.35 The temporary waivers granted to states as part of the federal government's coronavirus response increased flexibility with respect to benefit's eligibility should yield additional evidence about the value of removing barriers to program enrollment.36

Beyond SNAP, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)—a public health nutrition program that provides nutrition education, breastfeeding support and nutritious foods to low-income pregnant women and mothers of small children—also has a track record of cost-effectiveness and improvement in health outcomes. Other programs include the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), which provides 1-2 nutritious meals a day to students, depending on their family’s household income. Students can receive nutritionally balanced lunches at little to no cost each day they are in school. This program operates in public and non-profit charter schools (such as KIPP schools).

Although the NSLP provides meals to students throughout the school year, the program only slightly decreases the level of food insecurity in a community, since students may go without meals after the school day and during summer. The Food and Resource Action Center estimates the NSLP reduces food insecurity by about 4 percent among participants.37 To increase accessibility, some programs have expanded to include evening meals, and the Summer Food Service Program provides free meals to kids and teens in low-income areas when school is out. Moreover, the Child and Adult Food Program serves preschools which are not part of the NSLP.

State Actions to Address Food Insecurity

States have their own policy options to address food insecurity, including tailoring their approaches to reflect local differences in rural vs. urban settings, and supply side considerations like food deserts.

These state levers include:

- Community Needs Assessments to Understand Food Insecurity: Community needs assessments collect data on unmet community needs providing actionable information for their stakeholders.38 To assist states in assessing food insecurity, the CDC provides an extensive toolkit on how to conduct a community food needs assessment.39

The toolkit highlights states that have successfully completed these assessments. In Illinois, for example, researchers found that Chicago had disproportionally fewer supermarkets in low-income communities, which was thought to lead to other poor health outcomes.40 Their assessment provided recommendations aimed to address food insecurity through state and local government interventions.41 We did not find conclusive evidence, however, that shows these assessments reduce food insecurity. - Food Policy Councils: These councils operate at the state or local level and their activities typically include coordination of food actors, networking, information sharing and advocacy. Councils are commonly created by local, state, or federal governments, but they can also be established by non-governmental agencies. Research conducted by the CDC and 25 state health departments shows that food policy councils can increase access to healthy foods.42

- Removing Barriers to Food Donation through Legislation: In 1996, President Bill Clinton passed the Federal Bill Emerson Food Donation Act,43 which protected any person, gleaner or non-profit organization who donated food in good faith, and without gross negligence, from civil or criminal liability.44 Despite these protections, many restaurants and other institutions worry about the potential legal implications they could face for donating food. To address this, states can also provide protections,as California did when the state passed the Good Samaritan Food Donation Act.45

- Providing Reliable Transportation to Food Banks or Mobile Food Banks: Many individuals find it difficult or strenuous to make it to a brick-and-mortar food bank site. To increase accessibility, state Medicaid programs can repurpose non-emergency medical transport to cover transportation to and from food banks and soup kitchens. Additionally, states can consider bringing food to the people and utilizing non-medical transport as the delivery mechanism. Although there are no Medicaid models with records of providing this type of service, various non-profit and other organizations provide food delivery services to specific vulnerable populations.46

Is There a Role for Healthcare Payers and Providers in Food Insecurity?

As noted above, reducing food insecurity can improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare spending, especially when such programs are targeted to specific types of patients. For example, investments that reduce hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations for Type 1 diabetics could result in a net cost savings of between $946 to $1,346 per patient.47 Policymakers seeking to expand evidenced-based approaches to addressing food insecurity should partner with payers and providers to leverage these potential healthcare savings.

In early 2017, the Food Research and Action Center partnered with the American Academy for Pediatrics (AAP) to create a provider toolkit aimed at reducing food insecurity. While providing guides and tips for recognizing food insecurity, the toolkit also provides resources that pediatricians can connect their patients with. A 2017 study of the toolkit found that clinicians were able to identify food insecure households and that patients responded well to the screening, believing it showed caring.48 However, only 1 of the 122 food insecure households became enrolled in SNAP.49 Although the screening measures showed positive results, better methods for connecting food insecure patients with food resources are needed.

Hospitals can also reduce food insecurity in their communities. In a 2017 report, the American Hospital Association published a guide to assist hospitals in implementing screening tools in their clinical interactions and other strategies at the non-clinical, administrative level.50 The guide provides various questions that can be easily incorporated into annual wellness visits, and suggests including screening tools and reminders in electronic health records.51 Providing prescriptions for healthy food and having an on-site food bank were also listed as clinical options.52 The guide recommends incorporating food security in non-profit hospitals’ regular community needs assessments.53 Other suggestions include partnering with local food banks and organizations, investing in food systems (including food trucks and in-house food banks) and advocating at the city and state level to increase access to food in their communities.54

In addition, providers also have the ability to prescribe medically tailored meals to their patients. In a 2019 study, researchers found that participation in a medically tailored meal delivery program was associated with a steep reduction in the number of inpatient admissions of medically complex individuals.55 Not only does this positively impact the health of an individual, this can also lead to cost savings for the hospital and payers. In fact, the study showed a 16 percent reduction in overall healthcare costs in relation to inpatient admissions for patients who participated in the medically tailored meal program.56

There are also opportunities for payers to address food insecurity. For example, Health Partners Plan of Pennsylvania developed the Food-as-Medicine Program, which partnered with local organizations to provide food for their diabetic Medicaid beneficiaries. From this partnership, Health Partners saw a 27 percent reduction in hospital admissions, 7 percent reduction in ED visits and 16 percent reduction in provider visits among those who received the meals. Beneficiaries of the food-as-medicine program also saw positive changes in their HbA1c levels 6 months following their enrollment into the program.

Additionally, Humana has taken initiative through their Bold Goal initiative, a long-term strategy to address social determinants of health for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries.57 Through their meal delivery program, they were able to address the needs of seniors who were food insecure and observed health improvement among the population. Humana measured the impact of this program by examining the number of “unhealthy days” an individual reported over a 30-day period. In their 2019 report, five of the seven Bold Goal communities reported reduced numbers of unhealthy days, which is correlated with decreased numbers of provider visits and emergency room admissions.58

Conclusion

Food insecurity is one of the most pressing issues that face Americans today. Although particularly prevalent in low-income communities, income shocks mean that food insecurity could potentially strike many families. Expanding eligibility for publicly funded programs can have a positive impact on health outcomes for individuals who are food insecure and can reduce overall healthcare costs at the national level. Additionally, because of beneficial health effects, payers and providers have an incentive to invest in programs that will alleviate food insecurity among their beneficiaries, in coordination with other stakeholders.

Notes

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Determinants of Health: Know What Affects Health. (Accessed on April 20, 2020).

2. Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, et al., Household Food Insecurity in the United States in 2018, United States Department of Agricultue, Washington, D.C. (September 2019).

3. Feeding America, Impact of Hunger. (Accessed on March 1, 2020).

4. Feeding America, What is Food Insecurity? (Accessed on March 1, 2020).

5. United States Department of Agriculture, Definitions of Food Security. (Accessed on March 1, 2020).

6. Feeding America, What is Food Insecurity?

7. Ibid.

8. Wight, Vanessa, et al., “Understanding the Link Between Poverty and Food Insecurity Among Children: Does the Definition of Poverty Matter?” Journal of Children and Poverty (2014).

9. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Rural Health Information Hub, Rural Health and Access to Healthy Food. (Accessed on May 10, 2020).

13. Ibid.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, A Look Inside Food Deserts. (Accessed on March 1, 2020).

15. United States Department of Agriculture, Definitions of Food Security.

16. North American Industrial Classifications System, 2007 NAICS Definition: 445110 Supermarkets and Other Grocery (Except Convenience) Stores. (Accessed on Feb. 22, 2020).

17. Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, et al., Household Food Insecurity in the United States in 2018, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C. (September 2019).

18. United States Department of Agriculture, Definitions of Food Security.

19. Seligman, Hilary, Barbara Laraia and Margot Kushel, “Food Insecurity is Associated with Chronic Disease Among Low-Income NHANES Participants,” The Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 140, No. 2 (February 2010).

20. Garcia, Sandra, Anne Haddix and Kevin Barnett, Incremental Health Care Costs Associated with Food Insecurity and Chronic Conditions Among Older Adults, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. (August 2018).

21. Ibid.

22. Artiga, Samantha, and Elizabeth Hinton, Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity, Kaiser Family Foundation (May 2018).

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Swartz, Haley, Visualizing State and County Healthcare Costs of Food Insecurity, Feeding America (Aug. 5, 2019).

26. USDA, A Short History of SNAP. (Accessed May 10, 2020).

27. Household Food Security in the United States in 1995, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C. (September 1997).

28. Keith-Jennings, Brynne, Joseph Llobrera and Stacy Dean, “Links of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program with Food Insecurity, Poverty and Health: Evidence and Potential,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 109, No. 12 (December 2019).

29. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Chart Book: SNAP Helps Struggling Families Put Food on the Table. (Accessed May 11, 2020).

30. Dewey, Caitlin, “What Americans Get Wrong About Food Stamps, According to an Expert Who's Spent 2 Years Researching Them,” The Washington Post (April 4, 2017).

31. Food Waste Reduction Alliance, Analysis of U.S. Food Waste Among Food Manufacturers, Retailers, and Restaurants, Arlington, VA (2014).

32. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). (Accessed April 20, 2020).

33. Balbes, Maribelle, et al., State Level Program Access Review Guide, Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, Alexandria, VA (2012).

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Woloshin, Diane, Perspective: The Pandemic Has Created a Food Insecurity Crisis. The Federal Response Has Been Swift, but Is it Enough? Altarum Institute, Washington, D.C. (May 20, 2020).

37. Food Research and Action Center, Benefits of School Lunch. (Accessed April 20, 2020).

38. Healthcare Value Hub, Improving Value: Community Benefit and Community Health Needs Assessment, Washington, D.C. (Accessed on June 8, 2020).

39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Healthier Food Retail: Beginning the Assessment Process in Your State or Community, Atlanta, GA (2014).

40. The Food Trust, Stimulating Supermarket Development in Illinois, Philadelphia, PA (2014).

41. Ibid.

42. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, DNPAO State Program Highlights Food Policy Councils, Atlanta, GA (May 2010).

43. Public Law 104-210, “Bill Emerson Food Donation Act,” Passed October 1996.

44. Ibid.

45. California Law AB-1219, “California Good Samaritan Food Donation Act,” Passed November 2017.

46. Feeding America, Mobile Food Pantry Program, Washington, D.C.

47. Ibid.

48. Palakshappa, Deepak, et al., “Clinicians' Perceptions of Screening for Food Insecurity in Suburban Pediatric Practice,” Pediatrics, Vol. 140, No. 1 (July 2017).

49. Ibid.

50. American Hospital Association, Food Insecurity and the Role of Hospitals, Washington, D.C. (2017).

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid

54. Ibid.

55. Berkowitz, Seth, et al., “Association Between Receipt of a Medically Tailored Meal Program and Health Care Use,” JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 179, No. 6 (April 2019).

56. Ibid.

57. Humana, Human's Bold Goal. (Accessed April 27, 2020).