Tapping into the Benefits of Social Investments: Addressing Financing Silos

State and local communities are placing a greater emphasis on addressing the full spectrum of a patient’s clinical, behavioral and social needs. Multi-stakeholder approaches to increase and target social (or population health) spending, and coordinate efforts across the health and social services sectors, have been shown to improve outcomes and even save money on net for certain populations.1

However, program rigidity and other barriers can stifle needed investments, even if these investments pay for themselves on net. This research brief discusses the nature of these barriers and uses case studies and evidence review to explore the strategies to remove financing barriers and improve funding for population health.

High Returns from Targeted Social Investments

Some investments not only improve health outcomes, but they essentially pay for themselves. For example,

- Studies have found that every dollar invested in smoking cessation can save $2-3.2

- Ensuring that diabetics on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) don’t run out of food before the end of the month can reduce hypoglycemic episodes and, in turn, emergency department (ED) visits. Patients who experience food insecurity are nearly twice as likely to report such episodes.3 Investments that reduce hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations for Type 1 diabetics could result in a net cost savings between $946 to $1,346 per patient.4

- Community-based investments in nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation and prevention programs leading to a 5 percent reduction in rates of Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure could save more than $5 billion in healthcare spending.5

- Doing home remediation for severely asthmatic children can reduce ED visits and hospitalizations, improve health outcomes and school performance, with lasting effects into adulthood. One such program implemented by the Minnesota Department of Health saw a positive return on investment, which ranged from $5.25 to $1.61 for every dollar invested in home-based services for asthma patients.6

- A partnership between the Maine Medical Center and Southern Maine Agency on Aging to provide specialized meal delivery to high-risk Medicare patients saw savings of $3.87 for every dollar spent on meals.7

Many of these estimates do not account for additional long-term gains, like increased worker productivity, decreased absenteeism from school or work, improved quality of life and extension of healthy life expectancy.8

In addition to investments that “pay for themselves” in direct savings, myriad other social and health system interventions reliably improve health outcomes and are worth paying for because we value better population health. For example, the home-based intervention for pediatric asthma patients implemented by the Minnesota Department of Health saw a reduction in missed school days by an average of 2.42 days in a three-month period.9 Both types of valuable investments should be kept in mind as we explore financing mechanisms.

Barriers to Financing Targeted Investments to Address Social Determinants of Health

States—key stakeholders for improving outcomes—face many barriers as they try to integrate social and medical spending for the greater good. These barriers are the result of:

- clinical and social services that are siloed in separate and distinct programmatic funding streams;

- social services are not adequately reimbursed and the “health” business case for increasing social spending may not be clear; and

- there is often a mismatch between stakeholders who make investments and ones who realize savings and benefits down the road. Stakeholders do sometimes reap the benefits of their investments, but not enough to justify solely financing an initiative targeting social determinants of health.

Programmatic Barriers to Targeted Social Investments

In some instances, a stakeholder that could potentially reap savings and improve outcomes is stymied from making these investments due to program rules. For example, housing is a necessary precursor of health for individuals trapped in a cycle of crisis and housing instability due to extreme poverty, trauma, violence, mental illness, addiction or other chronic health condition. Without housing, these individuals struggle to adhere to medical regimens, take medication and manage their chronic conditions and are more likely to end up in the emergency room.10 For these individuals, housing can entirely dictate their health trajectory and the introduction of stable housing can yield a net system savings.11 Yet unless a waiver is acquired, the Medicaid program does not allow for federal financial participation (FFP or federal matching funds) to pay housing costs for non-institutionalized beneficiaries.12

Temporal Barriers to Targeted Social Investments

There are also temporal barriers. Many needed investments —for example, in early childhood education—have robust payoffs throughout the life of the child. But the future benefits in terms of worker productivity, higher incomes, lower incarceration rates, etc. can’t be readily accessed to pay for the intervention. States must annually balance their budgets and can’t recognize those future savings to fund social investments.

Stakeholder Mismatch

In addition, some stakeholders have little incentive to make certain types of investments. If the benefits occur too far into the future or are dispersed to people who aren’t part of the stakeholder’s patient population, the savings may not accrue to the stakeholders. As a general rule, we should not expect stakeholder to make investments if they will not reap the benefits—public spiritedness is useful but unlikely to motivate the full spectrum of needed social investments.

What qualifies as “good business” will vary by stakeholder. Hospitals, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), health plans, employers, and county, state and federal payers will consider questions such as: whether the intervention directly targets their population, how certain the benefits are, and when in the future the benefits occur.13 Examples of how these calculations might differ include:14

- In a fee-for-service system, providers have little incentive to coordinate with social services or to supply needed services directly, unless they are paid for their efforts.15

- As discussed further below, other methods of paying providers could affect their calculations. Under the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, Medicare reduces payments to hospitals with high rates of hospital readmissions within 30 days. With these altered incentives, hospitals may benefit from partnerships that integrate social and medical care.16

- Private health plans are concerned with the difference between what they collect through enrollee premiums and what they pay for covering healthcare expenses. Insurers may not see a benefit to investing in the long-term health of their enrollees because individuals are likely to change plans.17

- Government payers face a different calculation, they also face budgetary constraints. If a new program requiring a sizeable investment would result in long-term savings, Medicaid directors still have to consider short-term consequences like associated program cuts, taxes and debt. Political administrators tend to have short tenures and may not be around to see savings. State behavior is also shaped by policies around federal matching funds and grants.

- Employers purchasing insurance are primarily concerned with their ability to recruit and retain productive workers, while keeping costs low. They might be willing to make investments to increase workforce productivity in the short- and medium-term but not for the long-term or for non-workers.

Strategies to Increase Social Financing

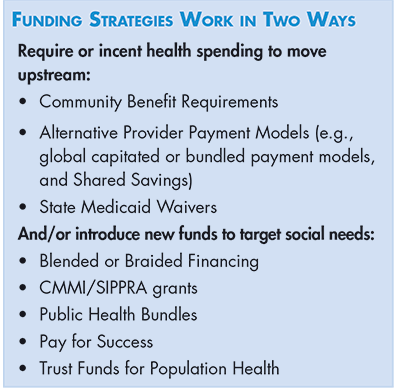

A significant set of approaches has been developed to address the financing challenges described above and to improve our ability to make wise investments that address social determinants of health. Broadly speaking, funding strategies work in two ways: 1.) requiring or incenting health spending to move upstream and 2.) introduce new funds to address social needs. (see Funding Strategies box).

A final strategy is to better aligning social investments with the natural incentives facing various stakeholders, in order to maximize the contributions of each.

Community Benefit Requirements

Nonprofit hospitals incur a community benefit requirement in order to receive an exemption from most federal, state, and local taxes. Under the “community benefit” standard, spending that promotes community health, in addition to charity care, count toward meeting the requirements for tax exemption. Some of these efforts include “community building activities,” which can involve investments in housing and making environmental improvements.18 Historically, the vast majority of community benefit spending by hospitals has been related to charity care—that is, providing patient care services for free or at a reduced charge.19 Only a small fraction has been spent on community health improvement—less than 8 percent according to one study.20

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes guidelines for obtaining tax exempt status, including requiring hospitals to conduct Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNA) and implement strategies to address said needs.21 Though, current federal guidance governing CHNAs is problematically vague, leaving a great deal open to interpretation.22 As a result, some assessments include perspectives from a rich diversity of community stakeholders, while others incorporate input from a select few.

For many reasons, experts are skeptical that this community benefit obligation is well positioned to address social determinants of health. For one, the current system focuses on the immediate service areas of hospitals, risks widening health disparities as suburban hospitals focus on relatively well-off communities, while urban hospitals have more limited resources to invest in their neighborhoods because of higher burdens of uncompensated care. In addition, the levels of investment are too low, infrequently coordinated with other social determinants of health efforts, and not always invested in evidence-based approaches to improving public health.

Finally, many large nonprofits operate like for-profits, paying high CEO salaries, spending reserves on state-of-the-art lobbies, and accumulating vast amount of surplus, the nonprofit hospitals equivalent of profit.23,24

This state of affairs suggests three things: improved accountability for nonprofits (or the imposition of taxes to fund public health initiatives); considering similar obligations for other health system nonprofit entities; and coordinating these efforts with other means of financing social investments, as described below. As an example, state governments can improve the utility of CHNAs conducted by nonprofit hospitals by requiring comprehensive, city-wide assessments that look across medical, behavioral and social sectors to identify unmet needs and assess the community’s ability to meet those needs.

Alternative Payment Models

Alternative-payment models (APMs) seek to reward healthcare providers (hospitals and doctors) for improved outcomes and quality, rather than the amount of care they provide. Not every provider is positioned to accept these types of payments but larger, integrated healthcare systems like hospital systems, ACOs, and HMOs may have the ability to use these approaches.

APMs encompass a wide range of approaches, but approaches that could incent upstream investments include: Shared Savings, bundled payments and capitated payment models. Because benefits must accrue fairly quickly (outcomes are typically assessed within the plan year), APMs may be better suited to interventions targeting patients with acute conditions as opposed to interventions with longer-term pay offs.

Shared Savings

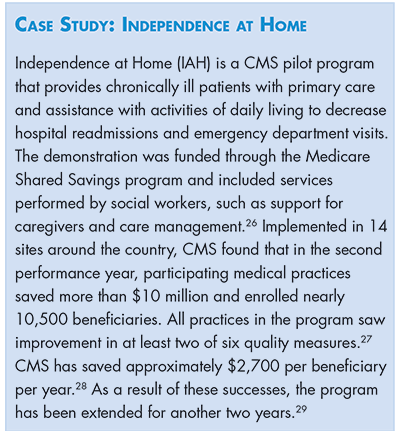

The Medicare Shared Savings program can be used to incentivize providers to reduce healthcare spending for a defined patient population. Providers coordinate services as part of an Accountable Care Organization (ACO), or a group of providers, physicians, hospitals and other care providers. The ACO is responsible for patient outcomes and quality of care. The payment amounts, which are based on historical payments, are risk adjusted to reflect the population’s health and medical needs that may affect the utilization of services. If providers meet a predefined set of access, cost and quality measures they receive a percentage of the net savings or a bonus from the federal agency that administers Medicare.25 Some states are using shared savings to incorporate social services into their ACOs. (See IAH case study box.)

Bundled Episode Payments

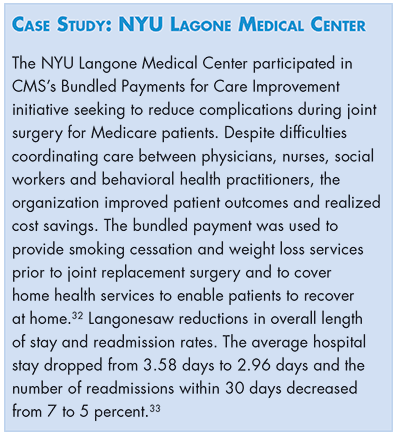

Bundled payments set a standard payment for all care associated with a clinical episode or for a specified period in order to promote coordination among providers and incentivize a reduction in unnecessary services.30 Theoretically, bundled payments can be used to pay for social services associated with a clinical episode. For example, services that help deliver specialized meals after acute gastrointestinal trauma. Ideally, payments would be tied to meeting quality targets.31 (See NYU case study box.)

Payment models affect the way risks and returns are shared when integrated partnerships deliver services. For example, if a community based organization (CBO) receives a bundled episode payment from a medical partner, the CBO is assuming risk if the case rate and service intensity is higher than anticipated. Other agreements, like Medicare Shared Savings, result only in upside risk for the ACO. The Commonwealth Fund ROI tool helps partners assess which financing model to use when integrating new services.34

Global Capitated Model

The global capitation model seeks to integrate healthcare delivery by providing a single payment to a care organization or physician group for all care for a defined population.35 This payment can be based off of historical costs for the community or patient population.36 Providers receiving capitation payments must meet quality targets in order to ensure that they are not withholding care.37

Capitation is meant to encourage provider to deploy a mix of services that result in better outcomes for the population they serve. Though, for the most part, payers are not required to include social services to receive their capitated payment, if the spending “pays for itself” over the short-run and improves outcomes, this payment structure allows the provider to keep the resulting savings or receive a quality bonus.

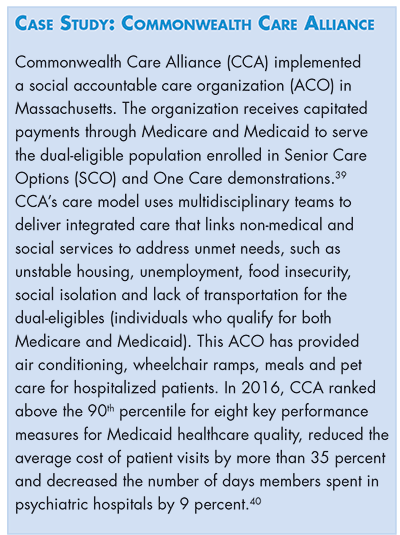

Many organizations lack the capital and infrastructure to manage this type of patient risk. Using risk adjustment tied to patients’ health status may help to mitigate some of this organizational risk.38 (See Commonwealth Care Alliance case study box.)

State Medicaid Waivers

Medicaid waivers, both section 1115 and 1915, offer a unique opportunity for states to pilot innovative programs that may not adhere to traditional Medicaid requirements set by the federal government. States can apply to test delivery system changes that may potentially improve care and reduce costs, so long as changes are budget neutral. If a waiver is granted by CMS, states can receive federal match for services delivered by non-traditional providers or in non-traditional settings.41

As noted above, there are certain things that traditional Medicaid cannot pay for (like room and board), but states have the flexibility to design waivers that include supports that encompass a broad range of services related to housing transition and sustainability. States have the ability to use 1115 waivers to extend coverage to additional populations, and to coordinate a variety of medical, behavioral and social services.42 As of July 2018, there are 16 approved delivery system reform waivers and 21 approved behavioral health waivers.43

Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) waivers, part of the broader 1115 wavier program, link provider funding to performance metrics. Under DSRIP, states can use waivers to change the way healthcare is delivered in inpatient and outpatient settings, as long as providers and states meet benchmarks. DSRIP waivers are being used to improve coordination among medical health, behavioral health and social service providers.44 Some states have concluded their DSRIP programs (California), whereas others will continue through 2021 (Washington). CMS has emphasized that DSRIP funds are a one-time, time-limited investment that states will need to sustain using other reform initiatives.45

Through Section 1915 waivers states can target individuals who need long-term services and supports and home and community-based services. For example, 1915c home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers are used to provide services to people who want to receive long-term care in their homes and communities, instead of in an institutional setting. States seeking to use a 1915c HCBS waiver must meet certain requirements like demonstrating that services are cost neutral and issuing reasonable provider standards to address the needs of the target population.46 Section 1915k, or community first choice waivers, also allow eligible Medicaid beneficiaries to receive home and community based services. With this option, states receive a 6 percent increase in federal matching funds. Unlike 1915c waivers, 1915k waivers have no target groups and are meant to provide integrated services without regard to an individual’s age or disability status.47 (See Oregon and New York case study boxes.)

Blended and Braided Financing

Many states have used Medicaid waivers to blend or braid funding from local agencies to coordinate social and medical care. Blended and braided financing allow organizations to pool funds that can be used to pay for a variety of services, like Medicaid funding for medical care and patient support, rent subsidies from state housing departments and more.

Through braided financing, several funding streams are combined to pay for related services. This model supports multi-stakeholder financing and keeps the funds in different streams so they can be tracked easily at the administrative level. In order to ensure each funding stream is being used to pay for eligible activities, regular reporting is required.

Blended funding, on the other hand, receives money from multiple sources but combines it into a single funding pool or stream. This allows for minimal administrative oversight and maximum flexibility.54

As an example, through braided funding, Steve, a homeless patient with addiction issues suffering from a chronic medical condition, is able to receive medical care, rent subsidies and substance abuse prevention services from Medicaid, the Housing Department and community programs through a coordinating agency. The separate funding streams pay for services they are authorized to pay for, but the patient does not have to deal with the headache of coordinating the back-and-forth from provider to counselor to provider. Through blended funding, various payers would pool funds that are used to pay for services that patients like Steve need, without having to worry about attributing costs to certain funding streams.55 (See Blending and Braiding case study boxes.)

Federal Grants

To encourage new models of coordination across social and health sectors, the federal government periodically provides limited duration grant funding.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation

While no grants are currently available, it is worth noting the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) recently awarded time limited grants to fund pilot program integration projects to test new payment and service delivery models.60 In 2012, CMMI awarded $1 billion in the first round of Health Care Innovation Awards to organizations focusing on meeting Triple Aim goals.61 Though no grants are currently available, CMS awarded 27 states and the District of Columbia second round awards starting in 2014.62 These awards used a pre-determined time period (generally short) to assess the model’s return on investment. (See CMMI case study box.)

Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA)

As part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, Congress passed the Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA).65 The legislation creates a pool of funds to support outcomes-based financing models. Social impact partnerships are available to entities that are able to produce one or more measurable outcomes that result in social benefit or savings. While not restricted to health, some of these metrics include: reducing rates of asthma, diabetes or other preventable diseases and improving birth outcomes and early childhood health among low-income families and individuals.66 As of this writing, awards have not yet been made.

Public Health Bundles

Public health bundles are an untested approach that would be established by a state or local public health department to deal with public health issues.67 Taking teen car accidents as an example, a state or local health department would establish a fund to receive annual payments from participating payers based on anticipated hospital costs of injuries to teenagers in motor vehicle accidents. The fund then is responsible for reimbursing payers for the actual care provided. To reduce payouts, the health department convenes a community coalition of public and private partners devoted to traffic safety.Savings would be reinvested in additional prevention efforts.

Though not yet being used, public health bundles would be a way for CBOs and clinical partners to work together to address underlying social determinants for common, costly public health problems. In theory, these can be coordinated with social impact bonds (described next) to reimburse investors for meeting outcomes targets.

Pay for Success

The pay for success (PFS) model creates public-private partnerships whereby the private partner makes an initial investment that addresses a social problem. The government partner then repays the investor based on improvements to predefined outcome or performance measures.68 The goal is for the end payer to save enough money when outcomes are achieved to justify repayments to initial investors.69

In a traditional PFS model, known as a social impact bond, the funders/investors provide upfront capital for a nonprofit service provider to deliver agreed upon services. At a later date, a government payer reimburses private funders once the specified outcomes are achieved by a service provider.70 This includes both a success payment, based on a cost-benefit analysis, as well as a repayment of the initial investment, usually based on an outcome trigger.71

A RAND study that looked at social impact bonds in the UK targeting socially isolated elders, people with multiple chronic conditions and those with disabilities and found that only one program realized net savings during a three-year evaluation period.72 However, outcomes may be different in the United States due to our country’s lower initial levels of social spending.

Presently, health focused PFS efforts in the US are still in their early stages and tend to focus on reducing healthcare utilization among the high-need, high-cost population by addressing social factors like homelessness and food insecurity.73

Concerns about whether this model would decrease public investment and whether public entities should invest directly in social determinants of health instead of working with private partners remain. When a private investor meets outcome or performance measures, the public entity has to pay that investment back with an additional return on investment. Key questions for advocates and other stakeholders include: Should government partners pay a premium on services that have already demonstrated success? Should public entities partner with social service providers on their own? (See South Carolina case study box.)

Trust Funds for Population Health

A trust fund for population health is funding raised to specifically address and support prevention and social interventions to improve the health outcomes of a targeted population. This can be used in combination with other approaches and funds can come from a variety of sources, including implementing a tax on hospitals or insurers or capturing savings from successful interventions.

As an example, the Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund (PWTF) in Massachusetts is tasked with gathering evidence of the cost-saving power of disease prevention. Inaugurated in 2012, this first-in-the-nation trust is a $60 million commitment over four years to support population health promotion efforts.76 The Trust Fund is financed through a one-time assessment on health insurers and large hospitals in the state. Mandated outcome measures include a reduction in healthcare costs and preventable health conditions.77 (See Boston case study box.)

Matching the Investment to the Stakeholder

To date, efforts to improve and target social investments as part of a vast patchwork of efforts that seek to leverage the financing opportunities available at the moment but are rarely part of systematic and sustainable plan.

Communities may want to consider more systematic approaches that tally the full spectrum of unmet social needs, marry this with data on the broad returns to society for meeting these needs and then consider which stakeholder is best positioned to make these investments. A new “health impact assessments” could be employed to estimate the broad and stakeholder specific health and economic future impact of not investing in social determinants of health.

Estimating the returns by stakeholder and overall to society, is of course easier said than done. The spectrum of benefits moves from cost-avoidance or savings that result from less tertiary care (e.g., lower hospital readmission rates or ED use) to the value of improved health outcomes (like A1C levels) to the long-term economic impacts like worker productivity improvements or lower incarceration rates. It can be difficult to agree not only on what is included in the spectrum of benefits but how to value the more intrinsic outcomes like improved quality of life, wellbeing and patient experience.80

Putting aside those difficulties, there is likely significant gains to be made by better tailoring the stakeholder to the investment. As discussed above, stakeholders vary in their ability to realize the benefits of a given social investment. For example, a state Department of Housing might invest in lead poisoning remediation in the home, but the future health benefits rarely accrue to the agency. Moreover, longer-term societal and economic impacts may benefit a variety of stakeholders, including “free riders” who might otherwise not make an investment.

These considerations lend support to the idea that a single pool of funds operated by a neutral party may lead to the greatest benefit.81 With this reasoning in mind, economists Len Nichols and Lauren Taylor developed a strategy based on the notion that upstream investments in social determinants of health should be regarded as a public good because they benefit a variety of sectors.82 To ensure appropriate investment by stakeholder, they envision a system that uses a financial neutral party or “trusted broker” to convene stakeholders. Calculating ROI for each stakeholder would require technical experts to use local data in conjunction with evaluations from similar communities. The investment will be worth pursuing if the collective value surpasses total cost. Based on what the broker decides each party should pay, entities would then pool funds to address common social problems, similar to the public health bundle model. As an example, authors modeled costs and benefits to various stakeholders investing in nonemergency medical transportation. They concluded that providers, especially hospitals, would lose revenues from a decline in utilization by paying consumers. As a result, a tax paid by other stakeholders to providers would encourage them to participate.

The “social determinants of health as a public good” argument could also lead to increased public sector investments. Without government investment, private actors may not have a large-scale impact on improving health outcomes for the public. For example, herd immunity created by vaccinations impacts the entire population and should be paid for by the government. Similarly, certain interventions targeting social determinants of health such as early-childhood education and housing effect society as a whole.83

Conclusion

Achieving the Triple Aim in healthcare is the gold standard that communities strive to attain. There is increasing evidence that approaches that increase and target social (or population health) spending, and coordinate efforts across the health and social services sectors, are integral to success in these aims. Unfortunately, we underinvest in these approaches, even in social investments that “pay for themselves.” To remedy this short-coming, this evidence review enumerates ways in which communities can move current health spending upstream and pursue new sources of funds. Moreover, we recommend taking a nuanced look at the type of investments being coaxed from provider, employer, health plan and other stakeholders, to ensure that incentives are properly aligned and to potentially gain funding from current “free riders.”

Notes

1. Artiga, Samantha, and Elizabeth Hinton, Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity, Kaiser Family Foundation (May 2018).

2. McCullough, J. Mac, The Return on Investment of Public Health System Spending, AcademyHealth (June 2018).

3. Seligman, Hilary, Elizabeth A. Jacobs, and Andrea Lopez, “Food Insecurity and Hypoglycemia Among Safety Net Patients with Diabetes,” JAMA (July 11, 2011).

4. Bronstone, Amy, and Claudia Graham, “The Potential Cost Implications of Averting Severe Hypoglycemic Events Requiring Hospitalization in High-Risk Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Using Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring,” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology (July 2016).

5. Trust for America's Health, Prevention for a Healthier America: Investments in Disease Prevention Yield Significant Savings, Stronger Communities, Washington, D.C. (February 2009

6. Minnesota Department of Health, Asthma Home-Based Services, http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpcd/cdee/asthma/homebasedsvs/index.html (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

7. Martin, Sarah L., et al., “Simply Delivered Meals: A Tale of Collaboration," American Journal of Managed Care (June 2018).

8. Trust for America's Health (February 2009).

9. Minnesota Department of Health, Asthma Home-Based Services, http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpcd/cdee/asthma/homebasedsvs/index.html (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

10. Kraus, Antoinette, “Philly's Heroin Camps Illustrate How Housing Instability Hurts Health,” The Philadelphia Inquirer (May 29, 2018).

11. The Corporation for Supportive Housing, Housing is the Best Medicine: Supportive Housing and the Social Determinants of Health, New York, N.Y. (July 2014).

12. Cassidy, Amanda, “Medicaid and Permanent Supportive Housing,” Health Affairs (Oct. 14, 2016).

13. Olson, Andrew, and Enrique Martinez-Vidal, Value-Based Purchasing: Making Good Health Good Business, Green & Health Homes Initiative, AcademyHealth and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (June 17, 2018).

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Boccuti, Cristina, and Giselle Casillas, Aiming for Fewer Hospital U-turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, Kaiser Family Foundation (March 2017).

17. McGuire, Jean F., Population Health Investments by Health Plans and Large Provider Organizations—Exploring the Business Case, Northeastern University, Boston, M.A. (March 2016).

18. James, Julia, “Nonprofit Hospitals' Community Benefit Requirements,” Health Affairs (Feb. 25, 2016).

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Rubin, Daniel B., et al., “Evaluating Hospitals' Provision of Community Benefit: An Argument for an Outcome-Based Approach to Nonprofit Hospital Tax Exemption,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 103, No. 4 (April, 2013).

23. Al-Agba, Niran, “The Fairy Tale of a Non-Profit Hospital,” Health Care Blog (April 25, 2017).

24. Bai, Ge, and Gerard F. Anderson, “A More Detailed Understanding of Factors Associated With Hospital Profitability,” Health Affairs, Vol. 35, No. 5 (May 2016).

25. Lazerow, Rob, What is the Medicare Shared Savings Program?, Advisory Board (November 2014).

26. American Academy of Home Care Medicine, Independence at Home Facts, https://www.iahnow.org/iah-demonstration/ (accessed on Oct. 5, 2018).

27. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Independence at Home Demonstration Performance Year 2 Results (August 2016).

28. Rotenberg, James, et al., “Home‐Based Primary Care: Beyond Extension of the Independence at Home Demonstration,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 66, No. 4 (April 2018).

29. Baxter, Amy, “Independence at Home Saves Medicare 10 Times More than ACOs," Home Health Care News (April 12, 2018).

30. Berenson, Robert, et al., Payment Methods and Benefit Designs: How They Work and How They Work Together to Improve Health Care (Bundled Episode Payments), Urban Institute (April 2016).

31. Healthcare Value Hub, Bundled Payments: Payment Reform with Promise, Research Brief No. 7 (July 2015).

32. Gruessner, Vera, “3 Ways Bundled Payment Models Brought Hospital Cost Savings,” HealthPayer Intelligence (January 2017).

33. NYU Langone Health, Bundled Payments Improve Care for Medicare Patients Undergoing Joint Replacement (2016).

34. Tabbush, Victor, Health Begins, Webinar: Risk/Reward Calculation Strategies (2018). https://register.gotowebinar.com/register/132235353842512899

35. Berenson (April 2016).

36. Alguire, Patrick, Understanding Capitation, American College of Physicians, www.acponline.org/residents_fellows/career_counseling/understandcapit.htm (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

37. Gillen, Emily, Alternative Payment Models: Reforming the Payment System, RTI International, Washington, D.C. (June 2018).

39. Maxwell, Jim, et al., The First Social ACO: Lessons from Commonwealth Care Alliance, JSI Research & Training Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (February 2016). https://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=16450&lid=3

40. Commonwealth Care Alliance, Outstanding Clinical Results, Boston, M.A. (January 2018).

41. Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Which States Have Approved and Pending Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers?, (2018).

42. National Conference of State Legislatures, Understanding Medicaid Section 1115 Waivers: A Primer for State Legislators (2017).

43. Kaiser Family Foundation, Approved Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers (Sept. 28, 2018).

44. Guyer, Jocelyn, et al. Key Themes from Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Waivers in 4 States, Kaiser Family Foundation (April 15, 2015).

45. Heider, Felicia, Tina Kartika and Jill Rosenthal, Exploration of the Evolving Federal and State Promise of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) and Similar Programs, National Academy for State Health Policy (August 2017).

46. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Home & Community-Based Services 1915(c), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/hcbs/authorities/1915-c/index.html (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018)

47. Cooper, Robin, Susan Flanagan, and Suzanne Crisp, Comparison of Medicaid 1915(c) Waiver, 1915(i), and 1915(k) State Plan Amendments, NASDDDS (2014).

48. Center for Health Care Strategies, State Payment and Financing Models to Promote Health and Social Service Integration, Trenton, N.J. (February 2015).

49. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Oregon Waiver Factsheet, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/demonstration-and-waiver-list/Waiver-Descript-Factsheet/OR-Waiver-Factsheet.html#OR40194 (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018)

50. Center for Health Care Strategies (February 2015).

51. Bachrach, Deborah, et al., Implications for Medicaid Payment and Delivery System Reform, Commonwealth Fund (April 2016).

52. New York State Department of Health, New York DSRIP 1115 Quarterly Report (May 2018).

53. Felland, Laurie, Debra Lipson and Jessica Heeringa, Medicaid 1115 Demonstrations: Examining New York’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Demonstration: Achievements at the Demonstration’s Midpoint and Lessons for Other States, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (April 2018).

54. Spark Policy Institute, Overview: Blending and Braiding Defined, Denver, C.O. (2014).

55. Clary, Amy, and Trish Riley, Braiding & Blending Funding Streams to Meet the Health-Related Social Needs of Low-Income Persons: Considerations for State Health Policymakers, National Academy for State Health Policy (February 2016).

56. Sandberg, Shana, et al., “Hennepin Health: A Safety-Net Accountable Care Organization for the Expanded Medicaid Population,” Health Affairs, Vol. 33, No. 11 (November 2014).

57. Center for Health Care Strategies (February 2015)

58. Hennepin Health, Hennepin Health-MNCare, Hennepin County, MN (2018).

59. Hostetter, Martha, Sarah Klein and Douglas McCarthy, Hennepin Health: A Care Delivery Paradigm for New Medicaid Beneficiaries, Commonwealth Fund (October 2016).

60. Center for Health Care Strategies (February 2015).

61. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Health Care Innovation Awards, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Innovation-Awards/ (accessed Oct. 24, 2018).

62. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Health Care Innovation Awards Round Two, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Innovation-Awards/Round-2.html (accessed Oct. 24, 2018).

63. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, HCIA Complex/High-Risk Patient Targeting: Third Annual Report (February 2017).

64. Ibid.

65. The U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, Congress Passes the Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA), http://impinvalliance.org/news-updates/2018/2/9/congress-passes-the-social-impact-partnerships-to-pay-for-results-act-sippra (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

66. Ibid.

67. Sharfstein, Joshua, “Public Health Bundles,” Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 95 (September 2017). https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/public-health-bundles/

68. Nonprofit Finance Fund, Pay for Success: Basics, https://payforsuccess.org/learn/basics/ (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

69. Skopec, Laura, Pay for Success in Health Care: Challenges and Opportunities, Urban Institute (April 2018).

70. Social Finance, What is Pay for Success?, http://socialfinance.org/what-is-pay-for-success/ (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

71. Nonprofit Finance Fund, Pay for Success: Glossary, https://payforsuccess.org/learn/glossary/ (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

72. RAND, An Investigation of Social Impact Bonds for Health and Social Care, https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/social-impact-bonds-for-health-social-care.html (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

73. Skopec (April 2018).

74. Nurse-Family Partnership, Annual Report 2017.

75. Nonprofit Finance Fund, Pay for Success, South Carolina Nurse-Family Partnership (Dec. 7, 2017). http://www.payforsuccess.org/project/south-carolina-nurse-family-partnership

76. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Georgia Health Policy Center, Financing Population Health, Wellness Trust: A State-Based Prevention Fund Example (October 2016). https://ghpc.gsu.edu/files/2016/10/RWJF_FinanceBook_Abridged_Version_Oct16.pdf

77. Institute on Urban Health Research and Practice, Northeastern University, The Massachusetts Prevention and Wellness Trust: An Innovative Approach to Prevention as a Component of Health Care Reform, Boston, M.A. (2012).

78. Boston Public Health Commission, Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund, http://www.bphc.org/whatwedo/physical-health/PreventionAndWellnessTrustFund/Pages/pwtf-home.aspx (accessed on Oct. 24, 2018).

79. Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund, Joining Forces: Adding Public Health Value to Healthcare Reform, Boston, M.A. (January 2017).

80. Tabbush (2018).

81. Olson and Martinez-Vidal (June 2018).

82. Nichols, Len, and Lauren Taylor, “Social Determinants as Public Goods: A New Approach to Financing Key Investments in Healthy Communities,” Health Affairs, Vol. 37, No. 8 (August 2018).

83. Worstall, Tim, "Why Government Should Spend More on Public Goods," Forbes (May 5, 2013).