Improving Value

Health Savings Accounts

What are HSAs?

Health savings accounts (HSAs) are tax-advantaged savings accounts designed to pay medical expenses. In order to fund the account, HSAs are paired with high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) meeting specific Internal Revenue Service (IRS) criteria.

Money invested in an HSA is intended to pay for qualifying medical expenses. Contributions, qualifying withdrawals and any earned interest are all tax-free. Money in an HSA rolls over from year to year if not spent.

Each year the IRS sets the maximum allowable annual HSA contribution, as well as the acceptable cost-sharing limits for qualifying HDHPs. For 2019:1

| $1,350 | Minimum deductible, individual |

| $3,500 | Max deductible and max contribution to HSA, individual |

| $6,750 | Max out-of-pocket limit, individual |

| $2,700 | Minimum deductible, family |

| $7,000 | Max deductible and max contribution to HSA, family |

| $13,500 | Max out-of-pocket limit, family |

HSAs differ from health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) and flexible spending accounts (FSA). All these accounts allow the individual to pay for medical care with pre-tax dollars, but the three arrangements differ in important ways:

|

|

HSA |

HRA |

FSA |

|

Who can establish the account? Who owns the account? |

Individuals or employers can set up these accounts. The individual owns the account. |

Only employers can set up HRAs and the account is “owned” by the employer. |

Only employers can set up FSAs and the account is “owned” by the employer. |

|

Who can fund the account? |

Individual or the employer |

Only the employer |

Individual or the employer |

|

Must be paired with HDHP? |

Yes |

No |

No |

Because the individual “owns” the HSA, the account can follow the person when they change jobs or retire, while an HRA and FSA cannot. In addition, employers designate how much, if any, of the monies in an FSA or HRA account can “roll over” to the next plan year. HSA amounts always roll-over.

What does the evidence say?

HSAs and HDHPs are components of so-called consumer-directed health plans. These plans aim to reduce unnecessary spending by giving consumers more responsibility for paying medical bills out-of-pocket. Proponents of these plans believe that “skin in the game” will lead people to become more savvy (discerning) consumers of healthcare, leading to more efficient spending.

Critics contend that they simply shift costs from employers to their employees and lead many consumers to forgo needed care due to cost. These critics point out that many individuals enrolled in qualifying HDHPs do not have sufficient income to fund an HSA at levels that would cover their deductible. Moreover, the progressive design of the nation’s income tax system means that lower-income employees will derive far less benefit, if any, from these tax avoidance schemes.

A significant body of research has shown that people enrolled in high-deductible health plans consume less healthcare, all other things being equal. Unfortunately, these enrollees consume less of both appropriate care and inappropriate care – failing to support the idea that high deductibles make them savvy shoppers. Moreover, these plans have a disparate impact – lower-income employees reduce outpatient visits and other types of care to a greater degree than employees with higher incomes.2

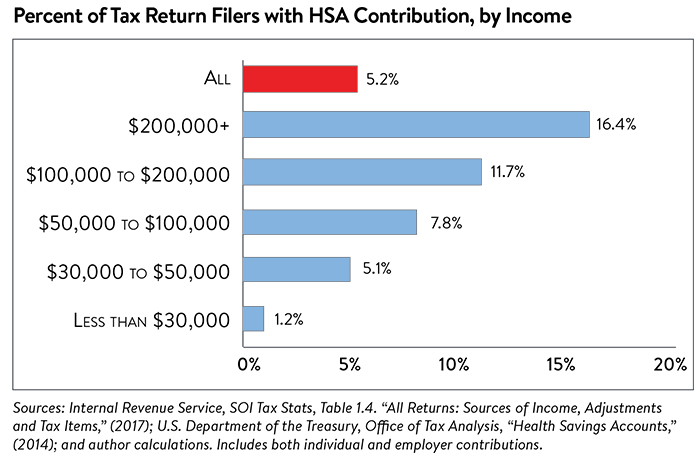

Research specific to the use of health savings accounts is limited but several studies find HSAs have been most popular among high-income households and large employers.3 In 2014 (the most recent Treasury data available), 11.7 percent of taxpayers with income between $100,000 and $200,000 contributed to an HSA, as did 16.4 percent of taxpayers with incomes of more than $200,000 (see Figure 1). In comparison, only 5.1 percent of taxpayers with income between $30,000 and $50,000 made such contributions. The U.S. Treasury finds that more than 60 percent of all HSA tax benefits accrue to families earning more than $100,000 annually.4

As already noted, high-income households benefit the most from the income tax-advantages conferred by an HSA. These households often use HSAs to save for retirement expenses because once a person reaches the age of retirement, they may use their HSA funds for non-medical expenses without paying a penalty.

From an efficiency and a fairness perspective, we need to rethink how the tax-expenditure associated with health savings accounts are allocated across U.S. households.

Notes

1. 26 CFR 601.602: Tax forms and Instructions, IRS (2018).

2. Fronstin, Paul, & Roebuck, M. Christopher, “The Impact of an HSA-Eligible Health Plan on Health Care Services Use and Spending by Worker Income, EBRI, No. 425 (August 2016).

3. Helmchen, Lorens, Brown, David, Lurie, Ithai, & Sasso, Anthony, “Health Savings Accounts: Growth Concentrated Among High-Income Households and Large Employers,” (March 2017). See also: https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-section-8-high-deductible-health-plans-with-savings-option/

4. "Families with Health Savings Accounts by Adjusted Gross Income, 2014," U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis (January 6, 2017).