Reducing Low-Value Care: Saving Money and Improving Health

In their seminal 2010 Workshop Series Summary: The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes, the Institutes of Medicine notes that unnecessary healthcare and inefficient care delivery represented 14 percent of our healthcare spending. This is spending that could be eliminated without worsening health outcomes.1

Despite the multitude of studies on the dangers and costs of providing low- and no-value care to patients, our healthcare system still delivers low-value care services. To help addres this source of waste and inefficiency, this brief defines low-value care, describes who is likely to receive this care, and identifies strategies to reduce it.

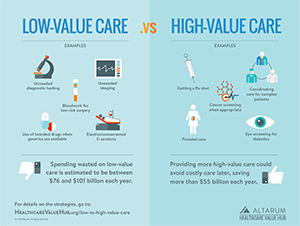

What is Low-Value Care?

Low-value care is defined as patient care that does not provide a net health benefit in clinical scenarios. Low-value care can be further parsed into services that are clinically inappropriate for particular clinical cases,2 services that provide little to no clinical benefit and are against patient preferences, and services that are done out of habit rather than scientific evidence.3

Measuring Low-Value Care

While there is wide-spread agreement that many unnecessary services are provided to patients, there are impediments to conclusively identifying low-value care and then measuring how prevalent it is.

Other than outright medical errors and other forms of "no-value" care, there is typically considerable "clinical nuance" involved with identifying low-value care. Clinical nuance recognized the benefit derived from a medical intervention is dependent on who is using it, who is delivering the service, and where it is being delivered.4 For example, a breast cancer screening can be high value for asymptomatic women in middle age, but is low value for most men as well as women who don't otherwise meet the guidelines.

No Single Source Identified Low-Value Services

There have been many initiatives to identify low-value services and a few researchers have attempted to harmonize these lists, nothing that not all recommendations have been translated into well-specified measures.

One comprehensive study of the literature identified these top five, most commonly published low-value care measures:5

- Pre-operative cardiac tests for non-cardiac low-risk surgery

- Antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infection

- Imaging for lower-back pain

- Cerical cancer screening

- Imaging for Sinusitis diagnosis

The study's authors noted that all five services are used in practice to help determine hospital provider payment bonuses and to determine ratings for physician quality reporting systems and went on to note that among the 115 low-value care measures identified, there was inconsistency in the evidence base used.

A second study also looked across the measures and overuse procedures developed by professional societies, quality improvement organizations and researchers, including the National Quality Forum, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force and the Choosing Wisely Campaign.6 Their review identified the top 26 low-value procedures based on overuse in the Medicare population and projected cost. Estimates of prevalence and cost were sensitive to how the measure was specified but some low-value care services that had particularly high costs included:

- Stress testing for stable coronary disease

- PCI/stenting for stable coronary disease

- Carotid artery disease screening for asymptomatic patients

- Renal artery stenting

- Colon cancer screening for elderly patients

- Head imaging for headache

Insufficient Data Impairs Our Ability to Measure Low-Value Care

Compounding the existence of myriad lists of low-value care (and reflecting varying strength of evidence), researchers also report that it is difficult to measure low-value care in a population because the claims and other administrative data typically used to identify low-value care may lack the variables needed to assess the clinical nuance.7,8

As a result, the literature in this field tends to provide highly aggregated system-level estimates or use a narrow look that examines just a few specific clinical services.9 Nonetheless, the second method still suggests the provision of low-value care is far too common.

- For example, one study looked at just sixteen low-value care services, concluding that nearly $418 million in healthcare spending (1.5%) was wasted on these services in 2014 for enrollees in both commercial (age 50+) and Medicare Advantage (age 65+) health plans.10 If these rates were similar in other covered populations, the amount of waste might total $5.4 billion for the U.S.

- Another study found more than $500 million was spent on 44 distinct low-value care services in the U.S. in 2014.11

- Using a strict definition for 26 measures of overuse, researchers found low-value care affected one-quarter of Medicare beneficiaries.12

Moreover, researchers working with claims data found that within regions, different types of low-value use generally correlates with each other, suggesting that the provision of low-value services may be driven by common factors.13 For that reason, claims-based measures—although limited in what they can detect—could be useful as a signal for broader problems regarding low-value care, including care that may be difficult to measure with claims.

Shocklingly, physicians self-report high levels of low-value care. A recent survey of physicians demonstrated that 65 percent of surveyed physicians thought that 30 percent of their services were wasteful and unnecessary.14

About Choosing WiselyChoosing Wisely is an initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Started in 2012, its mision is to promote discussions between clinicians and patients in order for patients to choose care that is evidence based, not duplicative, free from harm, and truly necessary. To that end, the initiative charged participating professional medical societies with creating lists of at least five services that should be discussed with patients prior to treatment. This charge created the List of Recommendations from which both patients and clinicians can use to identify tests and procedures that should be part of a discussion on appropriateness.15 While the List of Recommendations was not meant to be a list of low-value care services, but merely a list of services that should be discussed between patient and provider, several researchers have used a subset of the recommendations to measure the prevalence of low-value care in populations. 16, 17, 18 |

Who is Getting Low-Value Care?

Despite the difficulties in defining and measuring low-value care, researchers have determined there is a lot of low-value care occurring. When it comes to examining which populations are at particular risk for low-value care, the findings are often mixed.

A study examining the prevalence of certain low-value care services between commercially insured and Medicare beneficiaries found that low-value care seems to be unrelated to payer type or anticipated reimbursement. Rather, local practice patterns may have more of an influence on the rate of low-value care services.19 Nonetheless, a synthesis of several studies finds:20

- Patients with private insurance may be particularly exposed to unneccesary or low-value outpatient services, such as diagnostic imaging for uncomplicated headaches.

- Given its demographics, Medicare is heavily impacted by failures of care coordination in hospital and skilled nursing facilities.

Researchers have also studied disparities in the receipt of these services, and again findings are mixed. One study of commercially insured 18-64 year olds from across the United States found that low-value care spending occurred less among non-whites and lower-income patients, reflecting a potentially reverse disparities relationship.21 On the other hand, another study found that for selected low-value care services, Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to receive low-value care than whites.22 A third study, examining just nine low-value services, found that the delivery of low-value care was just as common in the Medicaid and uninsured populations as in the commercially insured population.23

Despite a lack of clarity on whether particular populations are disadvantaged by the receipt of low-value care, significant low-value care throughout our health system suggests that broad-based strategies to reduce low-value care are appropriate.

Strategies to Reduce Low-Value Care

Developing interventions to reduce the prevalence of low-value care has multiple challenges as well as opportunities.

In the only systematic review of the literature to date, Carrie Colla and colleagues suggest that multicomponent interventions that address both the patient and the clinician roles have the greatest potential to reduce low-value care. However, the team found more research is needed to understand the impact of insurer restrictions, pay-for-performance and risk-sharing contracts.24

Why Clinicians Order Low-Value Services

Changing providers' habits and practice patterns will be essential in combating low-value care services. In a study examining commercial insurance claims, researchers found that clinicians that ordered low-value imaging for back pain or headache visits on prior patients were more likely to continue that ordering practice.25 Ordering low-value imaging in other clinical scenarios also was a strong predictor of ordering low-value back and headache imaging. A qualitative study that examined the views of physicians regarding the overuse of low-value care services showed that they thought overuse continues to pose a real problem.

Physicians frequently cited patient expectations and time as barriers to changing their behavior.26 However, ownership of imaging equipment was also a strong predictor of ordering low-value imaging.27 Another study shows that physicians believe that patients with symptomatic conditions would have a hard time accepting that no treatment or services would be the best option for them.28 Moreover, close to 90 percent of surveyed physicians cited fear of malpractice as a reason for overtreatment.29 Even when providers pre-committed to following Choosing Wisely guidelines, occurrence of low-value services in certain areas remained unchanged.30

Clinician Focused Awareness Campaigns

Interventions that educate clinicians on prices and raise their level of cost consciousness may reduce the delivery of low-value care services. In a study using primary care physicians' self-reported use of low-value services and a Cost Consciousness Scale, researchers found that greater levels of cost consciousness was associated with lower use of low-value services.31 Further, physicians surveyed by the American Medical Association cited several potential solutions to reduce low-value treatments: further training on appropriateness criteria, easy access to outside health records in order to reduce redundant interventions and more practice guidelines.32

Interventions developed by state-level professional organizations may impact the use and prevalence of low-value care services. In an initiative by the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative (which represents 85% of the urologists in Michigan), the intitiative sought to reduce unnecessary imaging associated with bone scans and computerized tomography The Collaborative established criteria for when bone scans and computerized tomography was of low value and when the service could be considered high value. Educational clinics, toolkits with placards and scripts to educate patients as well as other practicioners were developed to reinforce when these images should be done and when they should not. Findings from this initiative show that unnecessary use of bone scans and computerized tomography decreased significantly. These outcomes suggest that a standardized protocol from a trusted entity accompanied by supports can decrease low-value services.33

In another example that used behavioral nudges, Cedars-Sinai hospital implemented a system that defines low-value services in a support tool embedded in the electronic health record (EHR).34 If a provider order a potentially "low-value" test or treatment, the EHR prompts the provider to consider other options before moving forward.35 This program has been in place for four years and evaluations show providers altered their treatment courses based on the feedback from the EHR and patient outcomes improved.36, 37

Accountable justification and peer comparisons can also be powerful approaches in reducing inappropriate care. A randomized clinical trial that looked to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions discovered that these two techniques significantly reduced rates of the inappropriate prescriptions of antibiotics.38 Accountable justifications prompted clinicians to write justifications for antibiotic prescriptions in the patient's EHR, following a notification that antibiotics may not be right for the patient. The peer comparison intervention ranked physicians on the number of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions they wrote and sent a note when the physicians was not a "top performer."

Provider Payment Reform

Provider payment reform is another strategy that many payers have looked to in order to reduce low-value care, including pay-for-performance contracts and risk-sharing contracts.

Pay-for-performance contracts incentivize providers to move away from harmful and costly low-value services in order to achieve bonuses tied to quality outcomes.

Bundled payments, capitation and other forms of global payment are all risk-sharing contracts that align provider financial incentives with the goal of reducing low-value services. As an example, when an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) faces a global budget for their patient population, providers are incentivized to reduce low-value care in order to stay within budget while still performing well on quality measures.39 The positive results from the first year of the Medicare Pioneer ACO program showed reductions in 31 low-value services.40 And, researchers determined that ACO-style risk contracts can discourage low-value care even without specifying which low-value care measures providers should reduce.41 However, although risk-sharing contract encourage providers to consider the value (including cost) of the services they deliver, there is the potential for providers to also reduce use of effective services, which must be guarded against.42

Patient Awareness

As noted above, physicians frequently cite patient expectations as a reason for ordering low-value care. A misalignment between what physicians and patients view as appropriate care can lead to overuse of low-value care services.

A cross-sectional survey of patients and physicians regarding appropriate care found that patients and physicians do have different perceptions of good care. Using two clinical vignettes based on Choosing Wisely initiatives, clinical scenarios were described in detail where respondents were asked to rate care on a five-point scale from poor to excellent. Physicians were much more likely to rate the care in the scenarios in a manner that was consistent with national guidelines, whereas patients were less likely to rate such care as good care.43

Research on how best to educate patients regarding low-value care has been mixed. In the study just cited, explaining the risks of the low-value care increased (by 15%) the proportion of patients who gave a high rating to the clinical scenario.44 In a study examining the effect of one-page evidence-based decision support sheets on low-value care services (covering prostate cancer screening for men ages 50-69, osteoporosis screening in low-risk women ages 50-64 and colorectal cancer screening for men and women ages 76-85), researchers found that the educational sheets alone were not enough to change a patient's intention to get the screening.45

Patient-Provider Shared Decision Making

Dual educational strategies for both physicians and patients and the method of delivery are likely important factors in reducing low-value care services. Shared decision making can address this communications gap between what patients want and what doctors think they want.

Shared decision making is a key component of person-centered healthcare.46 It is a process in which clinicians and patients work together to make treatment decisions and select tests, care plans and supportive services in a way that balances clinical evidence on risks and expected outcomes with patient preferences and values. Shared decision making is more than just the use of a decision aid. It requires cinician-patient engagement and successfully ensuring that both the provider's guidance and the patient's values and preferences are incorporated into the treatment decison.

Across several studies, as many as 20 percent of patients who participated in shared decision making chose less invasive surgical options and more conservative treatment than patients who did not use decision aids.47 In addition, the approach has been found to benefit both provider and patient, improving outcomes, treatment decisions and patient-physician satisfaction. Rates of shared decision making are low, though; in a study of 1,000 office visits, less than 10 percent of the visits met the minimum standards for shared decision making.48

Consumer Financial Nudges

The price of services can affect patient behaviors in choosing treatment; high out-of-pocket costs have been shown to reduce overall healthcare spending—but indiscriminantely, as patients reduce both high- and low-value care.49

Value-based insurance design (VBID) is a strategy to align patient out-of-pocket spending with the value of the medical services they are receiving. High-value services have low or no cost-sharing, but low-value services could be tagged with high cost-sharing. To date, there has been more experimentation with reducing cost-sharing to encourage receipt of high-value services than the latter approach. A challenge in identifying low-value servics for VBID is addressing the problem of clinical nuance in a way that doesn't make the insurance rules too complex for consumers.50

Example: The Oregon Health Leadership Task Force uses an evidence-based approach to identify nationally recognized overused diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. For these low-value services, the Task Force established a separate deductible and coinsurance rate twice as high for other services, like emergency departments visits, hysterectomies, spinal surgery and PET scans.51

Summary

There have been many strong initiatives to identify low-value services and raise awareness of excess utilization, but there is still much to be done to translate this research into concrete actions to reduce clinical use of low-value services. In part, this is due to the need for harmonization and better specification of low-value services. As one research team noted, "[m]any quality measures have been developed to assess underuse but few to assess overuse."52

While there are a number of strategies that have shown promise in reducing low-value care, there is no single intervention to minimize low-value care services. As Mafi and Parchman suggest: "In an ideal world—one united in reducing harmful and unnecessary care—bottom-up, multicomponent initiatives are adaptively combined with education, 'light-touch' financial alignment, careful surveillance of unintended consequences and softer yet equally powerful cultural levers—all harmonizing to finally tackle the problem of low-value care."53

Frameworks like the one described by Parchman, et al., rely on four necessary conditions to change behavior: prioritizing the reduction of low-value care; building a culture of trust, innovation and improvement; establishing a shared language and purpose; and committing resources to measurement.54 A change in culture from habitual practice patterns to adherence to guidelines and protocols will go a long way in addressing the prevalence of low-value care services.

Notes

1. Carfella-Lallemand, Nicole, "Reducing Waste in Health Care," Health Policy Brief, Health Affairs (December 13, 2012).

2. Lind, Keith, How Big is the Problem of Low-Value Health Care Service Use?, AARP Public Policy Institute (March 26, 2018).

3. Berwick, Donald, and Andrew Hackbarth, "Eliminating Waste in US Health Care," JAMA (April 11, 2012).

4. Center for Value Based Insurance Design, Understanding Clinical Nuance (accessed on October 12, 2018).

5. De Vries, Eline, et al, "Are Low-Value Care Measures Up to the Task? A Systematic Review of the Literature," BMC Health Services, Vol. 405, No. 16 (July 2014).

6. Schwarts, Aaron L., et al., "Measuring Low-Value Care in Medicare," JAMA Internal Medicine (July 2014).

7. Beaudin-Seiler, Beth et al., "Reducing Low-Value Care," Health Affairs Blog (September 20, 2016).

8. Chalmers, Kelsey, et al., "Developing Indicators for Measuring Low-Value Care: Mappying Choosing Wisely Recommendations to Hospital Data," BMC Research Notes (March 5, 2018).

9. O'Neill, Daniel P., and David Scheinker, "Wasted Health Spending: Who's Picking Up the Tab?" Health Affairs Blog (May 31, 2018).

11. Mafi, John N., et al., "Low-Cost High-Volume Health Services Contribute the Most to Unnecessary Health Spending," Health Affairs, Vol. 36, No. 10 (October 2017).

12. Schwartz (July 2014).

13. Ibid.

14. Lyu, Heather, et al., "Overtreatment in the United States," PLoS One, Vol. 12, No. 9 (September 2017).

15. Choosing Wisely, List of Recommendations (accessed on November 10, 2018).

16. Colla, Carrie, et al., "Choosing Wisely: Prevalence and Correlates of Low-Value Health Care Services in the United States," Journal of General Internal Medicine (February 2015).

17. Schwartz (July 2014).

18. Segal, Jodi, et al., "Identifying Possible Indicators of Systematic Overuse of Health Care Procedures with Claims Data," Medical Care (February 2014).

19. Colla, Carrie, et al., "Payer Type and Low-Value Care: Comparing Choosing Wisely Services Across Commercial and Medicare Populations," Health Services Research (April 2018).

21. Reid, Rachel, Brendan Rabideau and Neeraj Sood, "Low-Value Health Care Services in a Commercially Insured Population," JAMA Internal Medicine (October 2016).

22. Schpero, William, "For Selected Services, Blacks and Hispanics More Likely to Receive Low-Value Care Than Whites," Health Affairs (June 2017).

23. This study also looked at 12 high-value services, finding similar rates of delivery across payers. Barnett, Michael, et al., "Low-Value Medical Services in the Safety-Net Population," JAMA Internal Medicine (June 2017).

24. Colla, Carrie, "Interventions Aimed at Reducing Use of Low-Value Health Services: A Systematic Review," Health Care Research and Review (July 8, 2016).

25. Hong, Arthur, et al., "Clinician-Level Predictors for Ordering Low-Value Imaging," JAMA Internal Medicine (November 2017).

26. Bishop, Tara, et al., "Academic Physicians' Views on Low-Value Service and the Choosing Wisely Campaign: A Qualitative Study," Healthcare (May 25, 2016).

27. Hong (November 2017).

28. Zikmund-Fisher, Brian, "Perceived Barriers to Implementing Individual Choosing Wisely Recommendations in Two National Surveys of Primary Care Providers," Journal of General Internal (February 2017).

29. Lyu (September 2017).

30. Kullgren, Jeffry Todd, et al., "Precommitting to Choose Wisely About Low-Value Services: A Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised Trial," BMJ Quality & Safety (May 2018).

31. Grover, Michael, et al., "Physician Cost Consciousness and Use of Low-Value Clinical Services," Journal of American Board of Family Medicine (November 2016).

32. Lyu (September 2017).

33. Hurley, Patrick, et al., "A Statewide Intervention Improves Appropriate Imaging in Localized Prostate Cancer," Journal of Urology (May 2017).

34. LaPoint, Jacqueline, "3 Strategies to Decrease Low Value Care, Healthcare Costs," Revcycle Intelligence (April 9, 2018).

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Heekin, Andrew, et al., "Choosing Wisely Clinical Decision Supports Adherence and Associated Inpatient Costs," American Journal of Managed Care, Vol. 24, No. 8 (August 2018).

38. Meeker, Daniella, "Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial," JAMA (February 9, 2016).

39. Schwartz (July 2014).

41. Ibid.

42. Colla, Carrie, "Swimming Against the Current - What Might Work to Reduce Low-Value Care?" New England Journal of Medicine (October 2, 2014).

43. Warner, A. Sofia, et al., "Patient and Physician Attitudes Towards Low-Value Diagnostic Tests," JAMA Internal Medicine (August 2016).

44. Ibid.

45. Sheridan, Stacey L., et al., "A Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Alternative Forms for Presenting Benefits and Harms Information for Low-Value Screening Services: A Randomized Clinical Trial," JAMA Internal Medicine (January 2016).

46. Krishnan, Sunita, and Lynn Quincy, The Consumer Benefits of Patient Shared Decision Making, Healthcare Value Hub (forthcoming).

47. Ibid.

48. Braddock, Clarence, et al., "Informed Decision Making in Outpatient Practice: Time to Get Back to Basics," JAMA (December 22, 1999).

49. Healthcare Value Hub, Rethinking Consumerism in Healthcare Benefit Design (April 2016).

50. Fendrick, A. Mark, Dean G. Smith and Michael E. Chernew, "Applying Value-Based Insurance Design to Low-Value Health Services," Health Affairs (November 2010).

51. Kapowich, Joan M., "Oregon's Test of Value-Based Insurance Design in Coverage for State Workers," Health Affairs (Nocember 2010).

52. Schwartz (July 2014).

53. Mafi, John, and Michael Parchman, M., "Low-Value Care: An Intractable Global Problem with No Quick Fix," BMJ Quality and Safety (May 2018).

54. Parchman, Michael, et al., "Taking Action on Overuse: Creating the Culture for Change," Healthcare (November 10, 2016).