Six Categories of Healthcare Waste: Which Reign Supreme?

By Amanda Hunt, Policy Analyst

For several years, advocates, researchers and policymakers have relied on aging estimates of six domains of healthcare waste, identified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and Berwick and Hackbarth. The IOM report, released in 2010, estimated that at least one third of U.S. healthcare spending is wasted (i.e. doesn’t support better health outcomes) due to:

- failure of care delivery, such as poor adherence to clinical best practices;

- failure to coordinate care;

- overtreatment, including the provision of low-value care;

- unreasonably high prices (a.k.a., “pricing failures”); and

- administrative complexity.

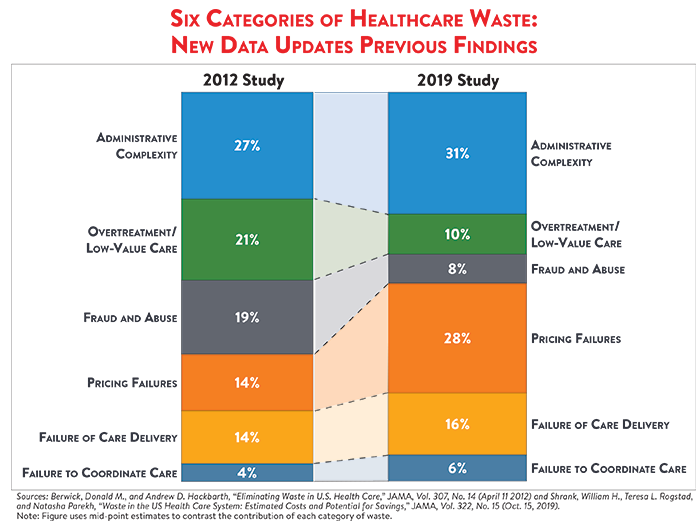

A subsequent 2012 study by Berwick and Hackbarth identified a sixth contributor – fraud and abuse – and calculated the contributions of each category toward the total wasted spending. These eye-opening statistics spurred extensive discussions of strategies to lower national healthcare spending through the elimination of waste.

A 2019 study by researchers at Humana and the University of Pittsburg School of Medicine updates these findings for the first time in nearly a decade and has yielded interesting results. Firstly, the estimated percentage of wasted healthcare spending has remained roughly the same – at approximately 25 percent – despite extensive payment and delivery reform efforts.

Perhaps more interestingly, the categories of healthcare waste that loom the largest have changed. Midpoint estimates from Berwick and Hackbarth’s study identified administrative complexity, overtreatment/low-value care, and fraud and abuse as the largest wasteful spending drivers, respectively. The updated estimates show that administrative complexity still reigns supreme, however, it is now followed by pricing failures and failure of care delivery (see Figure 1).

The 2019 analysis doesn’t speculate as to why the contributions of waste categories have changed over time. This may be because both the 2012 and 2019 studies are meta-analyses, limiting our ability to make “apples-to-apples” comparisons. Nevertheless, myriad studies identifying rising unit prices as the largest driver of year-over-year increases in total healthcare spending may explain the jump of “pricing failures” from fourth to second place.

Additionally, an article by distinguished economist Austin Frakt explains how our varying levels of understanding have catalyzed efforts to reduce spending in some areas (such as low-value care) and stymied action in others (like excess administrative spending). This is consistent with low-value care’s decline from second to fourth place and administrative complexity’s continued reign as the number one wasteful spending driver. According to Frakt, adhering to current best practices in all six categories “would eliminate only one-quarter of the waste [identified] – reducing [total healthcare] spending by about 5 percent.” Still, these efforts would produce a whopping $200 billion in savings per year.

The fact that nearly a quarter of U.S. healthcare spending – roughly $760-$935 billion each year – doesn’t support better health outcomes is deeply concerning, and suggests a need for greater policymaker and payer attention. Solving the problem of wasteful spending isn’t just an academic exercise – high healthcare costs are a serious, and sometimes life-threatening, burden for the individuals and families who ultimately shoulder the expense. The lack of progress demonstrated by this study, as well as the finding that best available evidence is insufficient to address it, warrants a renewed effort to reduce wasteful spending that doesn’t support better health.