When Antitrust Fails: Limiting Consumer Harm from Healthcare Consolidation

Competition in healthcare, while increasingly rare, helps control prices, encourages the delivery of high-quality products and services, and promotes consumer choice. However, antitrust laws designed to preserve competition have been largely ineffective since the 1990s, and persistent consolidation among providers and insurers has contributed to high (and rising) healthcare costs. As a result, states have relied upon alternative approaches to mitigate anti-competitive effects after mergers occur. This brief describes these efforts and identifies additional strategies to prevent future consolidation.

What are Antitrust Laws and Who Can Enforce Them?

Antitrust laws aim to preserve the benefits of competition in healthcare markets by prohibiting certain anti-competitive behaviors. Federal antitrust laws prohibit three categories of conduct that undermine competition:

- agreements by two or more businesses not to compete, or to limit competition;

- efforts by one or more companies to undercut competition by others in order to secure a monopoly; and

- mergers (or acquisition of business assets) that would significantly reduce competition.

Each of these categories has specific requirements and limitations reflecting the interpretation of the law by the courts. These laws can be enforced by the U.S. Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission and by states’ attorneys general. Most states also have their own versions of antitrust law, enforced by the state attorney general.1

What Happens When Mergers and Acquisitions are Allowed to Proceed?

Studies have found that antitrust laws are generally under-enforced.2 For a variety of reasons, many mergers and acquisitions are allowed to move forward, forcing regulators to grapple with the subsequent anti-competitive effects.3

In the healthcare sector, antitrust activity primarily focuses on mergers between competitors in a single market (a.k.a. horizontal mergers). However, evidence is mounting that mergers between organizations in different markets (i.e. cross-market mergers) and mergers between organizations at different stages of the supply chain (i.e. vertical mergers) can also have negative implications for consumers.4

Current Evidence on Healthcare Consolidation

Healthcare organizations typically argue that mergers improve efficiency and create economies-of-scale, improving quality and reducing costs. Yet little reliable evidence supports this claim.5 In fact, ample evidence demonstrates that healthcare mergers increase prices and that less competition may lead to lower quality.6,7 Mergers may also negatively affect other important aspects of the healthcare system, such as the healthcare workforce, health systems’ responsiveness to community concerns and access to care.8

State Options to Protect Consumers in Consolidated Markets

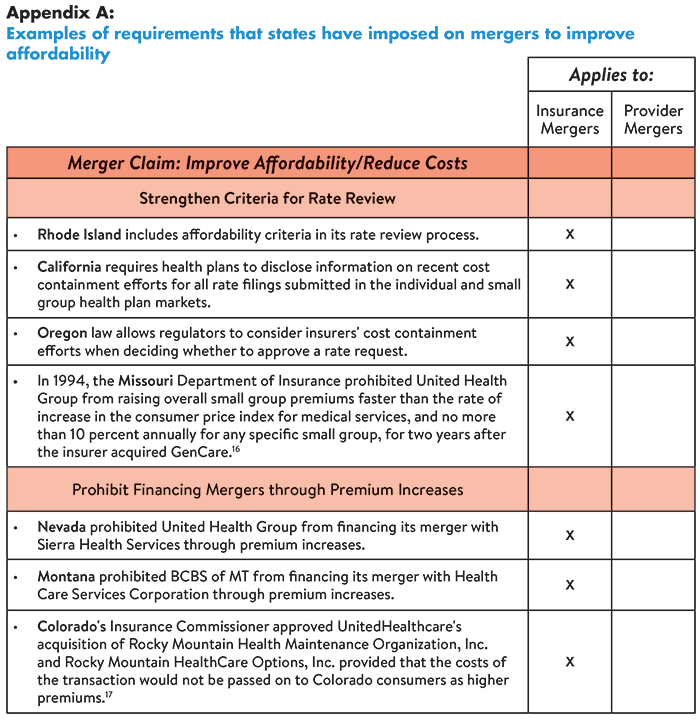

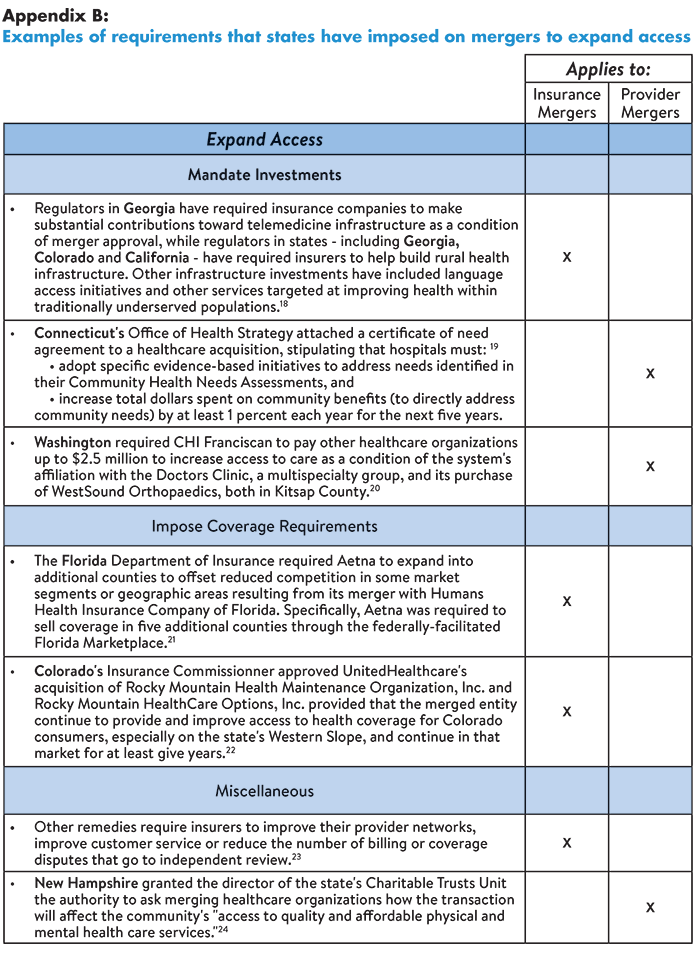

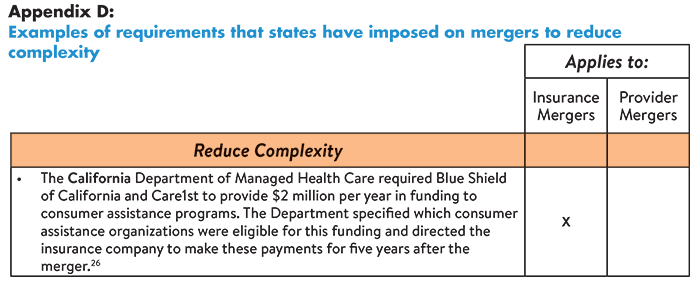

States can hold healthcare organizations accountable for delivering promised benefits by placing conditions on mergers designed to improve affordability, expand access, improve quality or reduce complexity. For example, some states have prohibited insurers from financing the cost of mergers by raising premiums. Other states have required organizations to invest in consumer assistance programs, infrastructure development and quality improvement initiatives. Specific examples of these requirements are provided below in Appendices A-D.

Alternatively, some states (including Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina) have attempted to mitigate harmful effects of consolidation by issuing certificates of public advantage (COPA)-legal agreements in which states exempt organizations from antitrust scrutiny in return for commitments to make public benefit investments and control healthcare cost growth.9 Evidence is still emerging on the effectiveness of this strategy,10 however, a study of North Carolina’s experience documented substantial risks.11

Other strategies that states can pursue include:12,13

- Strengthening community benefit requirements for nonprofit hospitals as a condition of their tax exemption;

- Establishing “any willing provider” laws that require insurers to contract with all interested providers (thereby reducing the bargaining power of insurers);

- Establishing “any willing insurer” laws that require providers to contract with any willing insurer (thereby reducing the bargaining power of providers); and

- Addressing pricing outliers through price caps14 or arbitration.

Strategies to Prevent Future Consolidation

A 2017 study by The Commonwealth Fund revealed that 90 percent of provider markets and 60 percent of insurer markets were either highly or super-concentrated as of 2016.15 To prevent further consolidation, states should consider:

- Establishing/strengthening antitrust laws and enforcement capacity pertaining to horizontal mergers, vertical mergers and anti-competitive practices; and

- Examining state-level regulatory burdens that increase costs associated with compliance (further incentivizing providers to consolidate).

Conclusion

Antitrust laws aim to promote healthcare competition by prohibiting anti-competitive behaviors; however, the laws are generally under-enforced. As a result, many healthcare mergers and acquisitions with anti-competitive effects move forward, increasing prices and potentially sacrificing quality of care. While the appropriate path forward is hotly debated (and will vary according to states’ political environments and unique regulatory structures), there is increasing support for alternative strategies to protect consumers from the potentially harmful effects of healthcare consolidation.

Notes

1. Slover, George, A Primer: How Antitrust Law Affects Competition in the Healthcare Marketplace, Altarum (formerly Consumers Union) Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (April 2015). https://healthcarevaluehub.org/advocate-resources/publications/primer-how-antitrust-law-affects-competition-health-care-marketplace

2. Morton, Fiona Scott, Modern U.S. Antitrust Theory and Evidence amid Rising Concerns of Market Power and its Effects: An Overview of Recent Academic Literature, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Washington, D.C. (May 2019). https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/modern-u-s-antitrust-theory-and-evidence-amid-rising-concerns-of-market-power-and-its-effects/. See also: Kades, Michael, The State of U.S. Federal Antitrust Enforcement, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Washington, D.C. (September 2019). https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/the-state-of-u-s-federal-antitrust-enforcement/

3. O’Hanlon, Claire E., “What Can State Regulators And Lawmakers Do When Federal Antitrust Enforcement Fails To Prevent Health Care Consolidation?” Health Affairs Blog (March 26, 2019). https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190320.450197/full/

4. Webinar: Hospital Competition and Hospital Mergers: What the Best Evidence Tells Us (Sept. 4, 2019). See also: https://tobin.yale.edu/news/webinar-hospital-mergers-nonpartisan-research-experts

5. A few studies have documented modest price reductions after mergers among providers, however, the reliability of the data source used is debated. See: Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. One study found that market concentration in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program was associated with higher premiums, however, the plans had a higher predicted probability of receiving a high-quality rating compared to MA plans sold in highly competitive markets. This finding suggests that a more nuanced approach than competition may be needed to ensure plan quality at the local market level. See: Adrion, Emily, “Competition and Health Plan Quality in the Medicare Advantage Market,” Health Services Research, Vol. 54, No. 5 (October 2019). http://www.hsr.org/hsr/abstract.jsp?aid=54367621500

8. O’Hanlon (March 26, 2019).

9. Brown, Erin C. Fuse, Hospital Mergers and Public Accountability: Tennessee and Virginia Employ a Certificate of Public Advantage, Milbank Memorial Fund, New York, N.Y. (Sept. 26, 2018). https://www.milbank.org/news/new-report-hospital-mergers-and-public-accountability-tennessee-and-virginia-employ-a-certificate-of-public-advantage/

10. U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC to Study the Impact of COPAs,” News Release (Oct. 21, 2019). https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/10/ftc-study-impact-copas

11. Brown, Erin C. Fuse, To Oversee or Not to Oversee? Lessons from the Repeal of North Carolina's Certificate of Public Advantage Law, Milbank Memorial Fund, New York, N.Y. (Jan. 17, 2018). https://www.milbank.org/publications/to-oversee-or-not-to-oversee-lessons-from-the-repeal-of-north-carolinas-certificate-of-public-advantage-law/

12. O’Hanlon (March 26, 2019).

13. Webinar: Hospital Competition and Hospital Mergers: What the Best Evidence Tells Us (Sept. 4, 2019). See also: https://tobin.yale.edu/news/webinar-hospital-mergers-nonpartisan-research-experts

14. Chernew, Michael E., Maximilian J. Pany, and Richard G. Frank, “The Case for Market-Based Price Caps,” Health Affairs Blog (Sept. 3, 2019). https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190826.369708/full/

15. Fulton, Brent D., Daniel R. Arnold, and Richard M. Scheffler, Market Concentration Variation of Health Care Providers and Health Insurers in the United States, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (July 30, 2018). https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/variation-healthcare-provider-and-health-insurer-market-concentration

16. Davenport, Karen, Advocates' Guide to Health Insurance Merger Remedies, Altarum (formerly Consumers Union) Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (June 2016). https://healthcarevaluehub.org/application/files/2315/6379/8125/Hub-Altarum_RB_12_-_Health_Plan_Merger_Remedies.pdf

17. Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, “Colo. Insurance Commissioner Approves UnitedHealthcare Acquisition of Rocky Mountain Health Plans,” News Release (Feb. 10, 2017). https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/dora/news/colo-insurance-commissioner-approves-unitedhealthcare-acquisition-rocky-mountain-health-plans

18. Davenport (June 2016).

19. Clary, Amy and Elinor Higgins, Oregon and Connecticut Hold Hospitals Accountable for Meaningful Community Benefit Investment, National Academy for State Health Policy, Washington, D.C. (Aug. 29, 2019). https://nashp.org/oregon-and-connecticut-hold-hospitals-accountable-for-meaningful-community-benefit-investment/

20. Meyer, Harris, “Medical Group Deals Face Growing Antitrust Scrutiny as Price Worries Rise,” Modern Healthcare (July 6, 2019). https://www.modernhealthcare.com/legal/medical-group-deals-face-growing-antitrust-scrutiny-price-worries-rise?

22. Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies (Feb. 10, 2017).

23. Ibid. See also: Colorado Office of the Attorney General, “Antitrust Challenge and Settlement to the UnitedHealth Group and DaVita Merger will Safeguard Competition, Cost, and Quality of Healthcare for Seniors in the Colorado Springs Area,” News Release (June 19, 2019). https://coag.gov/press-releases/06-19-19/

24. Doyle-Burr, Nora, “New N.H. Law Regulates Health Care Mergers,” Concord Monitor (Aug. 12, 2019). https://www.concordmonitor.com/Gov-Sununu-Signs-Bill-to-Increase-Scrutiny-of-Health-Care-Transactions-27616722?utm_campaign=

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.