Cost & Quality Problems

Medical Harm

A critically important area of excess spending and patient suffering is connected to care that is not only unnecessary, but harmful to patients. Preventing medical harm is also referred to as the practice of patient safety.1

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that 98,000 patients anually lose their lives due to medical harm.2 The IOM report sounded an alarm to the country, calling for sweeping changes to the health care system to improve patient safety.

While there has been some progress since the IOM's report,3 multiple studies confirm that progress is far too slow.4 Moreover, the IOM likely underestimated the amount of medical harm patients experience each year.

What is Medical Harm?

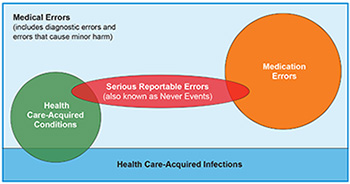

Among other things, medical harm includes:

- serious reportable events—more commonly called “never events;”5

- hospital-acquired conditions (HACs);

- healthcare-associated infections (HAIs);

- medication errors; and

- diagnostic errors.

Definitions can be tricky.6 Not all medical harm is preventable. For example, an adverse drug reaction can occur when there was no error in the process of prescribing the drug to a patient.7 Moreover, medical error is a failure in the delivery of medical care, regardless of the outcome. Therefore, it includes errors that did and did not result in harm.8

While medical harm spans all providers—hospitals, doctors, dialysis centers, nursing homes and outpatient surgical centers—most of what we know of this harm is from hospitals.

Preventable hospital readmissions—another source of wasteful spending—are in a category that is different from medical harm, but these are often connected to hospital-acquired infections and other types of medical harm.

While known to be large, precise extent of harm is not measured

While known to be a large problem, there has never been an actual count of how many patients are harmed while receiving medical care. Public hospital reporting systems and internal peer-review capture only a fraction of patient harm or negligent care. The precise number of medical harm events is debated and likely underestimated. Death certificates do not include a field to report if a patient died due to reasons related to medical error.9

Similarly, there are no comprehensive assessments of the costs that medical errors add to our nation's health care bill. Most studies are limited to the cost of a particular type of event or a particular population. However, we do know that the limited resources devoted to prevention — by hospitals, other health care providers and governmental agencies at the state and federal levels — are dwarfed by the resources spent to treat the consequences of this mostly preventable problem. Beyond finances, the human cost is staggering.

The following information provides a partial picture of the cost of medical harm.

- A 2019 meta-analysis found that 1 in 20 patients experience preventable medical harm and this harm leads to disability or death around 12 percent of the time.10

- A 2013 study estimated that medical harm kills 210,000 to 440,000 patients each year.11

- Annually, preventable medication errors likely affect more than 7 million patients and cost about $21 billion.12

Strategies to Address Medical Harm

The strategies that help reduce patient harm are fairly well-understood but unevenly implemented. Key strategies to measure and reduce medical harm include:

- Improving the accuracy, breadth and standardization of publicly reported medical harm across all settings.

- Aligning financial incentives to harm reduction, such as no payment for serious reportable events, reducing payments to the lowest performers and bundling payments in patient-centered integrated health delivery systems.

- Make the National Practicioner Data Bank—a database of all state and federal actions against US physicians, including malpractice settlements—available to the public. Currently, the data is available, but the names of doctors are confidential.13

- Establish a National Patient Safety Board—similar to the National Transportation Safety Board and the Consumer Finance Protection Agency—to represent the interests of patients/consumers by monitoring, investigating and promoting health care system changes that will lead to the elimination of medical errors.

Notes

1. World Health Organization, "Patient Safety."

2. Kohn, Linda T., et al., "To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System," Institute of Medicine (1999).

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, "AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2017," (January 2019).

4. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, "Adverse Events in Hospitals: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries," (November 2010); Landrigan, Christopher P., et al , “Temporal Trends in Rates of Patient Harm Resulting from Medical Care,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 363, No. 22 (November 25, 2010); Classen, David C., et al., “‘Global Trigger Tool’ Shows that Adverse Events in Hospitals May be Ten Times Greater than Previously Measured,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 4 (April 2011); Dreher, Melanie C., et al., "With Medical Errors Persisting, Why Aren't Cost-Effective Safety and Quality Solutions Gaining More Traction?" Becker's Hospital Review (December 31, 2019).

5. These errors are defined as "adverse events that are serious, largely preventable.” A list of “never events” is maintained by the National Quality Forum.

6. For a more complete description, see: "Medical Harm: A Taxonomy," Health Care Value Hub.

7. See Panagioti, Maria, et al., “Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ, Vol. 366: l4185 (July 2019).

8. Chamberlain, Catherine J., et al., “Disclosure of ‘Nonharmful’ Medical Errors and Other Events: Duty to Disclose,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 147, No. 3: 282-286 (May 2012).

9. Makary, Martin A. and Michael Daniel, “Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US,” BMJ, Vol. 353 (May 2016).

10. Panagioti, Maria, et al., “Prevalence, severity, and nature of preventable patient harm across medical care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ, Vol. 366 (July 2019).

11. James, John T., “A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care,” Journal of Patient Safety, Vol. 9, No. 3: 122-128 (September 2013). Nonetheless, a compilation of available studies found that around 1 in 20 (6%) of patients are affected by preventable harm in medical care, which leads to disability or death around 12% of the time.

12. da Silva, Brianna A. and Mahesh Krishnamurthy, “The alarming reality of medication error: a patient case and review of Pennsylvania and National Data," Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, Vol. 6, No. 4 (September 2016).

13. National Practicioner Data Bank, Website.