Cost & Quality Problems

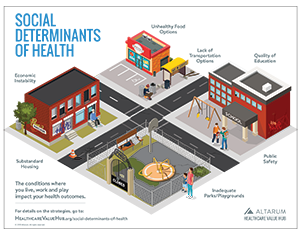

Social Determinants of Health

Achieving uniformly high health outcomes means thinking outside the doctor’s office. Our homes, schools, workplaces and community spaces all influence our health in substantial ways.

There is growing awareness that social determinants of health also have an outsized role to play. Researchers have determined that social determinants of health can explain up to 80 percent of an individual's health status, while medical care and access to services can explain up to 20 percent of health status.1 These factors include access to social and economic opportunities, resources and social supports in our neighborhoods such as quality of schooling and housing, workplace and neighborhood safety, and environmental quality of food, water and air.

|

Housing Insecurity Quality of housing as well as housing instability can affect individual and community health outcomes and contribute to health inequities. Poor quality housing can include environmental toxins like lead exposures, poor ventilation, dirty carpets, and pest exposures which can lead to poor health outcomes such as asthma. Housing instability encompasses many challenges, including trouble paying rent, overcrowding in a home, frequent moving and spending over 50 percent of income on housing or substandard living environments. These factors for a cost-burdened household can increase stress which directly impacts health. Additionally, spending excess income on housing means individuals and families must give up spending on other goods and services, often food and health care are the first services dropped.2 Homelessness, which is a distinct condition, affects health in many of the same ways as poor housing, such as stress from instability and exposure to environmental toxins on the street. Housing issues tend to be racially disparate as well; Black and Hispanic individuals are less likely to own houses and average lower housing equity compared to white families, even after controlling for resources, family structure and location.3 |

|

|

Food Insecurity Food insecurity is defined as the disruption of food intake or eating patterns due to a lack of money or resources. In 2016, 31.6 percent of low-income households were food insecure compared to the national average of 12.3 percent—a total of 15.6 million households.4 Being unemployed is the leading reason for food insecurity.5 There are racial and ethnic inequities related to food insecurity as well; Black, Non-Hispanic households were nearly 2 times more likely to be food insecure than the national average. Hispanic households experienced food insecurity at 1.5 times greater than the national average because Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately more low income.6 Research has demonstrated that white neighborhoods tend to have more grocery stores and options to healthy food than black neighborhoods, adding to these health inequities.7 Additionally, adults who are disabled are also at a higher risk for food insecurity because of limited employment opportunities and greater health care related expenses which reduce available income to buy food.8 |

|

|

Lack of Transportation Options Transportation’s connection to health care may not be immediately obvious. Our transportation system is an interconnected system of highways, roads, bridges, and public transportation system to connect people to each other and to their homes, jobs, schools, grocery stores and social activities. Transportation has increased mobility and access to good and services, especially for older adults and people with disabilities,9 this motorized system can have consequences like traffic crashes, air pollution, and physical inactivity, all of which may negatively impact health. Lack of access to transportation–and differences in how various communities can access transportation–lead to differences in health outcomes. |

|

|

Public Safety Public safety in a neighborhood is an important determinant of health. These safety considerations include environmental factors in worksites, schools and play areas such as exposure to toxic substances and other physical hazards. Safety considerations also include the “build environment”–housing and community design, and aesthetic elements like proper lighting and access to green spaces. Exposure to crime and violence is a tremendous burden on young people, families and neighborhoods. The impact of violence on health is not easily calculated with metrics like reduced quality of life, potential of young lives lost too soon, and neighborhoods where residents do not trust each other. Other costs of violence include medical care, criminal justice, social services and law enforcement.10 And while certain factors, such as the visible presence of police officers, can improve communal safety in neighborhoods, the increased tensions between people of color and police officers, means this communal safety may not be widely felt in every community. |

||

|

Quality of Education There is plenty of research to indicate early childhood education is a key factor to good health outcomes and achieving health equity.11 Conversely, stark differences in high school graduation rates, enrollment in higher education, and language and literacy skills all contribute to health inequities. Poor language comprehension can be one of the most difficult barriers to improve one’s health, especially for immigrants or people for whom English is not their primary language. Finding a translator can be difficult and time consuming. And, without a translator, access to care can be greatly diminished. Additionally, an individual’s degree of health literacy,12 or the degree to which people have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions, can also affect their health. This is highly correlated with education level and other economic factors, and is therefore an important social determinant of health.13 |

Healthy People 2020 set goals to address the Social Determinants of Health, because all citizens deserve an equal opportunity to make choices that lead to good health. An overarching finding is that the health sector needs to collaborate with other fields, like housing, education, childcare, community planning, transportation, and agriculture to achieve these goals. Healthy People 2020 also set a target to reduce the proportion of children and adults living in poverty, knowing that economic stability is key to ensure good health outcomes in the population.

Notes

1. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities What State Legislators Need to Know, National Conference of State Legislators (Dec. 1, 2013).

2. Taylor, Lauren, “Housing and Health: An Overview of the Literature,” Health Affairs, Washington, D.C. (June 7, 2018).

3. Flippen, Chenoa, “Racial and Ethnic Inequality in Homeownership and Housing Equity,” The Sociological Quarterly (2001).

4. Food Security Status of U.S. Households in 2016,U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (2016).

5. Nord, Mark, Alisha Coleman-Jensen and Christian Gregory, Prevalence of U.S. Food Insecurity is Related to Changes in Unemployment, Inflation, and the Price of Food, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (Sept. 3, 2014).

6. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences, USDA Economic Research Service, Washington, D.C. (June 2009).

7. Morland, K., Wing, S., et al., “Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with the Location of Food Stores and Food Service Places,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Jan. 22, 2002).

8. Huang, Jin and Kim Youngmi, “Food Insecurity and Disability: Do Economic Resources Matter?” Social Science Research Journal (January 2010).

9. Exploring Data and Metrics of Value at the Intersection of Health Care and Transportation: Proceedings of a Workshop, The National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine (2016)

10. Fact Sheet: Violence and Health Equity, National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence.

11. Hahn, Robert, et al., “Early Childhood Education to Promote Health Equity: A Community Guide Systematic Review,” Journal of Public Health Management Practices (September 2016).

12. Quick Guide to Health Literacy, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

13. Saha, Somnath, ”Improving Literacy as a Means to Reducing Health Disparities,” Journal of General Internal Medicine (August 2006).