Improving Healthcare Value in Rural America

|

In the national discussion about addressing high healthcare costs and improving quality, rural areas have been largely left behind. Although many people associate rural areas with the South, Midwest and West regions of the country, rural populations can be found in nearly every state. Nationally, approximately 60 million people live in rural areas, making rural healthcare value an important consideration for state and federal policy makers.1

Compared to more populated areas, less is known about the quality and cost of care provided in rural settings. Lack of data is due, in part, to the limited participation of rural providers in quality reporting initiatives.2 Limited resources, low case volumes, a high proportion of vulnerable patients and lack of rural-appropriate quality metrics are all factors that make it difficult for rural providers to participate.3 Furthermore, efforts to improve rural healthcare value suffer from a dearth of information related to cost. A number of studies compare Medicare expenditures and out-of-pocket costs for rural versus urban populations, but little information is publicly available on the unit prices of services provided to non-elderly adults.

Despite these data gaps, we know enough about rural healthcare delivery to state that healthcare value cannot be achieved with a one-size-fits-all approach. Given the distinctive challenges that rural populations and providers face, strategies to achieve healthcare value must be customized for rural areas. This research brief explains why rural areas are unique, identifies approaches that may have limited utility in rural settings and highlights promising models that improve rural healthcare value.

What Makes Rural Areas Unique?

Rural populations differ from urban populations in many ways. On average, people living in rural areas are older, poorer and sicker than the general population. They are more likely to smoke and be obese, and live in isolated areas, making it difficult to access needed services like preventative, primary, specialty and emergency care.4 Because of the relative absence of large employers, people living in small towns are less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance.5 Rural residents—particularly those living in states that did not expand Medicaid—are more likely to be uninsured. Not surprisingly, they are also more likely to delay or forgo medical care due to cost.6 Ultimately, the combination of these factors results in poorer health status and shorter life expectancy among rural populations compared to their urban counterparts.7

In addition to having different patient populations, rural areas differ from urban areas in the challenges faced by healthcare providers. Not only do rural providers treat a greater proportion of high-need patients, but they generally have fewer resources available to meet those needs. Dwindling patient volumes, reimbursement cuts and bad debt resulting from a high proportion of low-income, under- or uninsured patients are some of the many factors that financially strain rural providers, creating challenges to delivering high-quality care.8 For these and other reasons, rural areas generally struggle to attract and retain physicians, causing the majority of rural markets to have few practicing providers. The trend of rural hospital and pharmacy closures may also limit access to healthcare services, further contributing to poorer rural health outcomes.

What Healthcare Value Strategies are Ineffective in Rural Settings?

There is widespread acceptance that improving healthcare value is likely to require interventions on the part of payers and policymakers (as well as voluntary initiatives) to: identify services with excessive prices; identify and eliminate waste and low-value care; ensure the proper provision of high-value care and invest appropriately in the upstream, social determinants of health. Due to the distinct differences between rural and non-rural areas, some commonly used interventions to improve healthcare value may be largely ineffective in rural settings. Examples of strategies with limited potential in rural America might include reducing costs through provider and payer competition, reference pricing and consumer price shopping.

Provider and Payer Competition

As noted above, rural areas often suffer from healthcare provider shortages. Lack of competition allows rural providers to negotiate more favorable reimbursement rates than those in urban areas, thereby creating a financial disincentive for insurers to enter these markets.9,10 Payers’ reluctance has left many rural counties with only one or two carriers offering plans to individuals, allowing participating insurers to shift the high prices negotiated by providers to consumers by raising premiums. Limited insurance options force rural consumers to pay the higher premiums or remain uninsured.Urban areas are less affected by this problem, as the larger number of providers reduces bargaining power.11

Reference Pricing

Referencing pricing aims to reduce healthcare costs by setting a standard price that an insurer or employer is willing to pay for a drug, procedure or service and requiring beneficiaries to pay charges incurred in excess of that amount. In theory, reference pricing motivates consumers to “vote with their feet” in order to avoid paying more than the reference price.12 Case studies of this strategy have found that providers who originally charged more than the reference price lowered their prices, with the bulk of the savings going to the payer.

Reference pricing is unlikely to reduce costs in rural areas for several reasons. First, provider shortages make it difficult for insurers to build adequate networks of providers that charge prices within the reference price for a particular service.13 Additionally, providers’ bargaining power makes it difficult for payers to secure the payment concessions that are often necessary to realize significant cost savings.14

Consumer Price Shopping

Consumer price shopping has been proposed as a way to decrease rising healthcare costs. The idea is to increase cost-sharing so that consumers have “skin in the game,” incentivizing them to shop for healthcare services the way they do for other goods and services.

For both urban and rural patients, there are a number of problems with this rationale.15 Most notably, it fails to acknowledge that healthcare is not like other markets. The majority of healthcare services are not “shoppable,” meaning that consumers either do not have the time (in the case of an emergency) or the information necessary to make informed decisions. Furthermore, in situations where patients are in a position to choose between multiple providers, quality and loyalty may influence decisions more than cost.16

But the overriding consideration for rural patients is that lack of choices reduces the value of “shopping.” As already noted, some rural patients may only have access to one specialist who is in-network and located within a reasonable driving distance, eliminating the benefit of comparison shopping.17 Moreover, rural residents without insurance already have tremendous “skin in the game” and it seems clear that this has not resulted in a delivery system that provides healthcare at a level and price that is accessible for many patients.

What Healthcare Value Strategies are Best for Rural Areas?

It is important to note that the unique circumstances of rural areas do not prevent rural providers from delivering high-value care. To the contrary, high-performing rural health systems that address underlying social determinants of health and deliver care efficiently exist, and serve as powerful models that can be replicated in other communities (see box on page 4).18 Initiatives that contribute to the realization of high performing rural health systems include efforts to monitor and address provider supply, telehealth, interdisciplinary care coordination and—possibly—all-payer global budgets.

|

Spotlight on High-Performing Rural Health Systems North Dakota: A Cooperative Ethos With the majority of its population residing in small, geographically dispersed communities, North Dakota experiences many challenges common to rural areas. Surprisingly, the state consistently ranks in the top half of states on the Commonwealth Fund’s Scorecard on State Health System Performance. This success is due, in part, to the tradition of cooperation among the state’s healthcare providers, facilitating the sharing of scarce resources and expertise. Much of the healthcare in North Dakota is delivered by six integrated health systems composed of regional clinic networks and small, rural hospitals affiliated with larger urban hospitals. Telemedicine and telepharmacy networks support the rural health workforce and promote collaboration by allowing providers to send and receive patient data in real time. Additionally, nearly half of the state’s 31 Critical Access Hospitals participate in formal networks, with some hospitals sharing administrators and equipment like information technology networks. These connections improve providers’ ability to deliver high quality care by enhancing coordination and efficiency. Source: McCarthy, Douglas, et al., The North Dakota Experience: Achieving High-Performance Health Care through Rural Innovation and Cooperation, The Commonwealth Fund (May 2008). The Franklin Cardiovascular Health Program: A Community-Based Approach to Health The Franklin Cardiovascular Health Program (FCHP) is a long-running community health improvement initiative in Franklin County, Maine. Established in 1974, the FCHP originally sought to combat high rates of hypertension, but has since expanded to include detection and control of hyperlipidemia, tobacco cessation and diabetes management. The FCHP uses a community-based clinic model, deploying nurses and trained community volunteers into communal spaces to encourage periodic screening and health education. Nurses provide referrals for patients with uncontrolled medical conditions and send screening results to patients’ local primary care providers. In return, physicians refer patients to the FCHP for monitoring between office visits. Franklin County residents participating in the program have demonstrated marked improvements in hypertension control, elevated cholesterol control and smoking quit rates. Additionally, hospitalizations per capita were lower than expected for the measured period. Lower hospitalization rates are estimated to have saved approximately $5.5 million in hospital charges for Franklin County residents per year. The model’s success has been attributed to a number of factors, including support from a broad array of community stakeholders, an unusually long and consistent intervention period and widespread acceptance by county residents. Source: Record, N. Burgess, et al., “Community-Wide Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Programs and Health Outcomes in a Rural County, 1970–2010,” JAMA, Vol. 313, No. 2 (Jan. 13, 2015). |

Workforce Management: Monitoring and Addressing Provider Supply

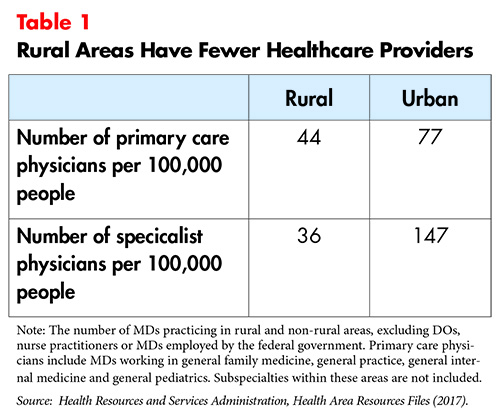

One of the greatest challenges to delivering high-quality care in rural areas is the relative scarcity of qualified medical professionals (see Table 1). Data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Area Health Resource Files reveals that approximately 90 percent of rural counties are wholly or partially designated primary medical Health Professional Shortage Areas.19 Within these areas, more than 38 million people lack adequate access to primary care.20 The challenges associated with recruiting physicians to rural areas are well documented.21 They include:

- Patient volumes that are too high or too low—In some communities, the demand for medical care may be greater than a single physician can provide. Doctors practicing in these locations often report feeling overworked and at high risk of burn-out.22 Other communities may not have enough residents to sustain a physician’s practice, causing providers to gravitate to more populated areas.

- Larger Medicare and Medicaid populations—Rural communities typically have a high proportion of Medicare and Medicaid patients. Physicians treating these patients are generally reimbursed at a lower rate than they are for treating commercially insured patients, creating a financial disincentive to practice in rural locales.

- Lower quality of life—Beyond the professional challenges, personal considerations such as limited employment options for spouses and lack of cultural opportunities may make life in a small town less desirable for physicians accustomed to metropolitan areas.23

The federal and state governments have developed a number of strategies to address the maldistribution of providers across the U.S.24 At the federal level, the National Health Service Corps, a subsidiary of HRSA, offers scholarships and loan repayment for primary care professionals—including physicians, dentists, nurse practitioners and physician assistants—to practice in underserved regions.25 The Corps also grants funding for states to administer their own loan repayment programs.26 Through its J-1 Visa Waiver/Conrad State 30 program, HRSA allows non-citizen international medical graduates to remain in the U.S. after their training in exchange for service in a designated Health Professional Shortage Area or Medically Underserved Area.27 Evidence suggests that the program successfully increases providers’ willingness to practice in rural areas in the short-term, although retention rates decrease over time.28,29

In addition to operating federally-supported loan repayment programs, states’ efforts to strengthen the rural health workforce include investing in recruitment initiatives targeted to middle and high school students, and establishing rural residency training programs.30 The University of Kansas School of Medicine offers admissions preference to applicants raised in rural areas (as these individuals are more likely to return to their hometowns to practice), while other schools have opened campuses in small towns to increase the number of local residents that apply.31,32 Partnerships with community hospitals encourage students to remain in the area after graduation.

Additionally, the majority of states have passed legislation to expand non-physician providers’ “scope of practice.” This strategy aims to address shortages of licensed physicians by authorizing other qualified medical professionals, like nurse practitioners and physician assistants, to provide many of the same services.33,34 Cost-effectiveness studies show that, in some circumstances, non-physician providers can provide an equivalent level of care at a lower cost than physicians.35,36

In 2014, Missouri passed legislation creating a new type of non-physician provider called an “assistant physician.” Licensed assistant physicians are medical school graduates who did not complete a residency, but are authorized to practice primary care alongside a physician in one of the state’s provider shortage areas.37,38 Assistant physicians are not to be confused with physician assistants. The latter do not attend medical school (and therefore cannot use the title “Dr.”), can practice medicine with varying degrees of physician oversight in primary or specialty care and are not restricted to practicing in underserved areas. As the first state to pass such legislation, Missouri’s approach has yet to be evaluated in terms of assistant physicians’ ability to deliver high-quality care.

Other healthcare professionals who do not provide direct medical care—like community health workers—support the rural healthcare workforce by serving as part of integrated care teams for complex patients with unmet social needs (see care coordination discussion below).

Telehealth

The use of telehealth has improved the quality of care available to rural populations by expanding access to specialty care.39 Telehealth can be used to facilitate both provider-to-provider interactions and patient-to-provider interactions electronically. This capability is particularly important in geographically isolated areas, where few specialists practice. Two types of telehealth showing promising results in rural settings are electronic consultation and telemedicine. Electronic consultation refers to two-way communications between local primary care physicians and specialists, while telemedicine connects patients to specialists.

Project ECHO is one example of how electronic consultation has been used to increase rural patients’ access to specialty care. The goal of the program is to “de-monopolize knowledge and amplify local capacity to provide best practice care” by creating virtual communities for providers to share expertise and acquire new skills. Each week, local primary care providers participate in teleconferences with specialists based out of an academic hub. Participants present de-identified patient cases, receive feedback and work with the specialists to establish a plan for treatment.40 Project ECHO “clinics” share best practices for more than 55 specialties, including hepatitis C, HIV, substance use disorders, diabetes, autism, palliative care and crisis intervention.41 Studies show that the model effectively develops subspecialty expertise over time, and that specialty care administered by local providers is as safe and effective as that provided by a specialist.42,43 Furthermore, the ability to regularly interact with colleagues may increase primary care providers’ professional satisfaction, improving retention in rural communities.

With telemedicine,patients can communicate directly with specialists across the state to address health needs beyond the expertise of local providers. These interactions can include live videoconferencing, “store-and-forward” transmission of images or information and remote patient monitoring.44 The reported benefits of telemedicine are wide ranging, including improved access to specialists, increased patient satisfaction and improved health outcomes.45 A limited number of studies found evidence of cost savings, although increased utilization resulting from expanding access may increase spending on upstream services in an effort to decrease the use of more costly services down the road.46,47,48

Despite its merits, barriers like inadequate reimbursement structures and lack of broadband capability inhibit the widespread adoption of telehealth in rural settings. Furthermore, licensure requirements preventing providers from treating patients in states where they are not licensed can undermine the goal of increasing access to specialists, regardless of geographic location. Federal and state efforts to address these barriers include providing funding and technical assistance for rural telehealth programs, investing in infrastructure improvements and establishing the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact.49,50

Care Coordination

Poor underlying health status, lifestyle factors and access issues put rural residents at high risk of developing multiple chronic conditions that are costly to treat and require the expertise of multiple providers. These high-cost, high-need—or complex—patients represent a minority of the general population, but drive a significant portion of healthcare spending. Care coordination programs designed to treat patients holistically have emerged as an important strategy to deliver care efficiently and reduce unnecessary costs for complex patients. Some models integrate medical care with dental, behavioral and/or home health services, while others go even further to incorporate efforts to address social determinants of health like access to transportation, adequate housing or healthy food. Social-medical models, in particular, have been shown to improve health outcomes for complex patients.51

Care coordination programs are incredibly diverse, but analysis of successful models reveals some common themes. The most effective programs are highly targeted, meaning that care teams use evidence-based criteria to determine which patients are most likely to benefit. Often, this involves a comprehensive assessment of patients’ medical, functional, social and behavioral needs.52 By being highly targeted and focusing on the most complex cases, these programs realize significant improvements in health outcomes and potentially even cost savings.

Additionally, effective care coordination requires an efficient information exchange. All participants in a patient’s interdisciplinary care team must be able to access up-to-date and comprehensive information in a timely manner. This requirement not only applies to the use of electronic record keeping systems, but also extends to relationships between team members.

Effective programs must also use trained care coordinators. Care coordinators serve as the glue for the interdisciplinary care team, facilitating coordination and communication between the patient and the interdisciplinary care team. Like other members of the team, care coordinators’ roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined. They can be nurses, social workers or patient navigators by trade, but they should also be experts on local resources and the factors contributing to health disparities within their communities.

Finally, successful programs consistently evaluate performance to monitor progress. Tracking quality measures related to patient experience, health outcomes, process improvement, community and population health and cost savings allows care teams to quantify positive impact and identify areas for improvement.53

Lack of a standardized definition prevents researchers from conducting rigorous side-by-side effectiveness comparisons of diverse care coordination programs. Independent evaluations show that some programs have achieved their goal to deliver high quality care, while others have attained mixed results. Barriers to successful implementation in rural areas include inadequate reimbursement for care coordination activities, shortages of—or far distances between—healthcare providers, and fewer public health programs.54

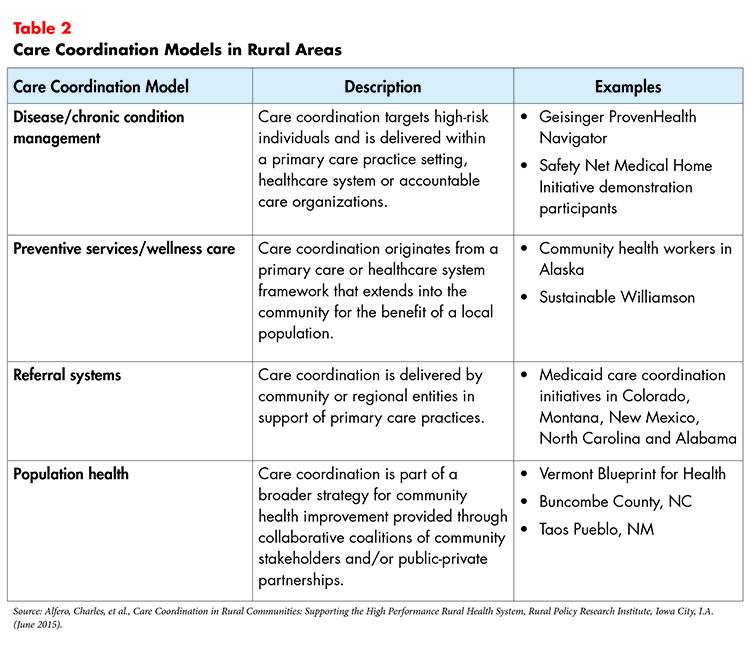

There are currently four types of coordination models that are positively impacting rural health outcomes today (see Table 2).

All-Payer Global Budgets

Ensuring the provision of high-quality care is only half of the healthcare value equation. Excess spending that cannot be linked to better health outcomes is equally indicative of low-value care. High prices are particularly burdensome in low-income rural communities, where a larger percentage of the population may be uninsured.

In recent years, states have experimented with alternative payment models to combat rising costs. Maryland’s all-payer model uses global budgets to control per capita hospital expenditures by requiring that all payers (Medicare, Medicaid and private insurers) pay hospitals a prospectively-set, fixed amount for the total number of inpatient, outpatient and emergency services provided annually. Hospitals are responsible for expenditures in excess of the amount set by the state’s Health Services Cost Review Commission, thus creating an incentive to reduce unnecessary utilization.

Maryland’s rural hospitals were early adopters of these global budgets, with all ten using the reimbursement model by 2010.55 Hospital leaders reported that prospective payments alleviated the pressure to fill hospital beds and allowed rural hospitals to invest in prevention and community services as a way to reduce future spending.56 Global budgets were expanded to all acute care hospitals in Maryland in 2014. Evaluations show that savings in per capita hospital revenue growth exceeded expectations. Quality indicators—such as preventable hospital-acquired conditions and readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries—also improved.57,58

Maryland’s early success with global budgets has generated interest in other states. In January 2017, Pennsylvania—in partnership with the federal Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation—initiated the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, which seeks to avoid rural hospital closures by using global budgets to stabilize revenue streams. Additionally, administrators hope the payment structure will give struggling hospitals the flexibility to better address the unique healthcare needs of local populations.59 Consistent with the CMS goal to transition from a volume- to value-based system, participating hospitals must formulate strategies to “improve quality, increase access to preventative care and create savings to the Medicare program.” The project will run for seven years, concluding on Dec. 31, 2023.60

Conclusion

Like many areas of the country, rural communities suffer from inconsistent healthcare value. However, the distinct differences between rural and non-rural environments make it impossible to improve poor value with a one-size-fits-all approach. For example, interventions that might successfully address high prices in urban settings may not work in rural markets—particularly those that attempt to exploit provider and insurer competition, or price variation among providers.

But with these challenges lies great opportunity. Promising models that seek to address access issues and underlying social needs—in addition to medical needs— have been shown to improve rural health outcomes and may also save money over time. Still, barriers exist that make it difficult for rural providers to invest in quality improvement and cost reduction initiatives. Overcoming them may require more, or at least wiser, spending in order to realize better health outcomes and decreased expenditures down the road.

Increasing the availability of meaningful data will also strengthen efforts to achieve healthcare value by helping researchers develop a more thorough understanding of cost and quality in rural areas compared to other geographic settings. This will enable stakeholders to better assess the current state of rural healthcare value to serve as a baseline from which to measure progress. Additionally, case studies highlighting existing high performing rural health systems (similar to the examples above) would provide valuable insights into overcoming challenges unique to rural communities. Having the necessary tools to identify where we are, where we want to go and how we are going to get there is vital to our mission to improve outcomes, decrease costs and reduce disparities among rural populations.

Ultimately, the realization of high performing rural health systems will likely require a shift from traditional hospital-based care to an emphasis on primary and preventive care, supported by emergency and community services.61 Some major hospital systems have anticipated this transition, tailoring services to meet the specific needs of local populations.62 Aligning resources according to demand is challenging for a health system with a single governing agent, but even more difficult to execute in communities with multiple independent providers. Changing financing and payment systems are one way to incentivize shared decision-making in pursuit of a meaningful realignment of services.

Notes

1. U.S. Census Bureau, “New Census Data Show Differences Between Urban and Rural Populations,” News Release (Dec. 8, 2016).

2. Thompson, Kristie, et al., CMS Hospital Quality Star Rating: For 762 Rural Hospitals, No Stars is the Problem, North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, Chapel Hill, N.C. (June 2017).

3. National Quality Forum Rural Health Committee, Performance Measurement for Rural Low-Volume Providers, Washington, D.C. (Sept. 14, 2015).

4. Foutz, Julia, Samantha Artiga, and Rachel Garfield, The Role of Medicaid in Rural America, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Menlo Park, Calif. (April 25, 2017).

5. Stanford eCampus Rural Health. Healthcare Disparities & Barriers to Healthcare, Stanford, Calif.

6. Rural Health Information Hub, Healthcare Access in Rural Communities, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/healthcare-access (accessed on Aug. 10, 2017).

7. Singh, Gopal K., and Mohammad Siahpush, “Widening Rural-Urban Disparities in Life Expectancy, U.S., 1969-2009,” American Journal of Preventative Medicine, Vol. 46, No. 2 (February 2014).

8. Topchik, Michael, Rural Relevance 2017: Assessing the State of Rural Healthcare in America, Chartis Center for Rural Health (2017).

9. Cusano, David, and Kevin Lucia, Implementing the Affordable Care Act: Promoting Competition in the Individual Marketplaces, The Commonwealth Fund, Washington, D.C. (February 2016).

10. Morrisey, Michael A., et al., Early Assessment of Competition in the Health Insurance Marketplace, RAND Corporation and Brookings Institution (Dec. 8, 2015).

11. Abelson, Reed, Katie Thomas, and Jo Craven McGinty, “Health Care Law Fails to Lower Prices for Rural Areas,” New York Times (Oct. 23, 2013).

12. Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, information page on reference pricing, https://healthcarevaluehub.org/improving-value/browse-strategy/reference-pricing/ (accessed on Sept. 10, 2017).

13. Mitts, Lydia, How to Make Reference Pricing Work for Consumers, Families USA, Washington, D.C. (June 2014).

14. Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, information page on reference pricing.

15. Quincy, Lynn, Rethinking Consumerism in Healthcare Benefit Design, Research Brief No. 11, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (April 2016).

16. Heath, Sara, “Price Transparency Tools Receive Tepid Patient Reactions,” PatientEngagementHIT (July 5, 2017).

17. Ibid.

18. Rural Health Value Project, Innovation in Rural Health Care: Contemporary Efforts to Transform into High Performance Systems, Iowa City, Iowa (May 1, 2016).

19. Health Resources and Services Administration, Health Area Resources Files (2017). https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/ahrf.aspx

20. Health Resources and Services Administration, Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics, Table 2, https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false (accessed on Sept. 7, 2017).

21. McGrail, Matthew R., et al., “Mobility of US Rural Primary Care Physicians During 2000–2014,” Annals of Family Medicine, Vol. 15, No. 4 (July/August 2017).

22. Lukens, Jenn, “Counteracting the Darkness of Physician Burnout,” Rural Roads, National Rural Health Association (Winter 2017).

23. Advisory Board, “Why Rural America Doesn't Attract Doctors,” Daily Briefing (Sept. 2, 2014). https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2014/09/02/why-rural-america-doesnt-attract-doctors

24. Barbey, Christopher, et al., “Physician Workforce Trends and Their Implications for Spending Growth,” Health Affairs Blog (July 28, 2017).

25. National Health Service Corps, Loan Repayment, https://www.nhsc.hrsa.gov/loanrepayment/index.html (accessed on Aug. 12, 2017).

26. National Health Service Corps, State Loan Repayment Program, https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/loanrepayment/stateloanrepaymentprogram/index.html (accessed on Aug. 12, 2017).

27. Rural Health Information Hub, Rural J-1 Visa Waiver, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/j-1-visa-waiver (accessed on Aug. 10, 2017).

28. Patterson, Davis G., Gina Keppel, and Susan M. Skillman, Conrad 30 Waivers for Physicians on J-1 Visas: State Policies, Practices, and Perspectives, Rural Health Research Center, Seattle, Wash. (March 2016).

29. National Health Service Corps, National Advisory Council, Retention and the National Health Service Corps, Meeting Presentation, Washington, D.C. (Jan. 10, 2013). https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/corpsexperience/aboutus/nationaladvisorycouncil/meetingsummaries/011013retention.pdf

30. National Conference of State Legislatures, Closing Gaps in the Rural Primary Care Workforce, Denver, Col. (August 2011).

31. University of Kansas Medical Center, Scholars in Rural Health, http://www.kumc.edu/school-of-medicine/education/premedical-programs/scholars-in-rural-health.html (accessed on Aug. 10, 2017).

32. Wirth, Tammy, Osteopathic Med Schools Like Kansas City University Answer The Call For More Doctors, KCUR (Feb. 23, 2017). http://kcur.org/post/osteopathic-med-schools-kansas-city-university-answer-call-more-doctors#stream/0

33. Larson, Eric H., et al., How Could Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants Be Deployed to Provide Rural Primary Care?, Rural Health Research Center, Seattle, Wash. (March 2016).

34. Van Vleet, Amanda, and Julia Paradise, Tapping Nurse Practitioners to Meet Rising Demand for Primary Care, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Menlo Park, Calif. (Jan. 20, 2015).

35. Ewing, Joshua, and Kara Nett Hinkley, Meeting the Primary Care Needs of Rural America: Examining the Role of Non-Physician Providers, National Council of State Legislatures, Denver, Col. (April 2013).

36. Jones, Shyloe, Provider Scope of Practice: Expanding Non-Physician Providers’ Responsibilities Can Benefit Consumers, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (November 2017).

37. Lieb, David A., Missouri Targets Doctor Dearth, Expands First-in-Nation Law, WSB-TV (May 14, 2017).

38. Missouri Division of Professional Registration, Missouri Board of Registration for the Healing Arts, http://pr.mo.gov/healingarts.asp (accessed on Aug. 15, 2017).

39. Patel, Kavita, et al., “Transforming Rural Health Care: High-Quality, Sustainable Access To Specialty Care,” Health Affairs Blog (Dec. 5, 2014).

40. University of New Mexico School of Medicine, About ECHO: Model, https://echo.unm.edu/about-echo/model/ (accessed on Aug. 11, 2017).

41. University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Project ECHO: Right Knowledge, Right Place, Right Time, https://echo.unm.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ECHO_One-Pager_11.17.16.pdf (accessed on Aug. 11, 2017).

42. Aurora, Sanjeev, et al., “Partnering Urban Academic Medical Centers and Rural Primary Care Clinicians to Provide Complex Chronic Disease Care,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 6 (June 2011).

43. Aurora, Sanjeev, et al., “Outcomes of Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection by Primary Care Providers,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 364, No. 23 (June 1, 2011).

44. Marcin, James P., Ulfat Shaikh, and Robin H. Steinhorn, “Addressing Health Disparities in Rural Communities Using Telehealth,” Pediatric Research, Vol. 79, No. 1-2 (Jan. 1, 2016).

45. Vo, Alexander, et al., Benefits of Telemedicine in Remote Communities & Use of Mobile and Wireless Platforms in Healthcare, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Tex.

46. Schadelbauer, Rick, Anticipating Economic Returns of Rural Telehealth, NTCA–The Rural Broadband Association, Arlington, Va. (March 2017).

47. Ashwood, J. Scott, et al., “Direct-To-Consumer Telehealth May Increase Access To Care But Does Not Decrease Spending,” Health Affairs, Vol. 36, No. 3 (March 2017).

48. Krishnan, Sunita, Telemedicine: Decreasing Barriers and Increasing Access to Healthcare, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (November 2017).

49. Rural Health Information Hub, Telehealth Use in Rural Healthcare, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/telehealth (accessed on Aug. 11, 2017).

50. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact is a legal agreement among states that increases access to healthcare in rural and underserved areas by allowing eligible physicians to provide telemedicine services across state lines. To learn more, visit http://www.imlcc.org/.

51. Huffstetler, Erin, and Lynn Quincy, Addressing the Unmet Medical and Social Needs of Complex Patients, Research Brief No. 17, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (February 2017).

52. National Academy of Medicine, Effective Care for High-Need Patients: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes, Value, and Health, Washington, D.C. (2017).

53. Alfero, Charles, et al., Care Coordination in Rural Communities: Supporting the High Performance Rural Health System, Rural Policy Research Institute, Iowa City, Iowa (June 2015).

54. Rural Health Information Hub, Rural Care Coordination, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/care-coordination (accessed on Aug. 16, 2017).

55. Rural Health Value Project, Global Budget Process as an Alternative Payment Model, Iowa City, Iowa (2017).

56. Sharfstein, Joshua M., et al., An Emerging Approach to Payment Reform: All-Payer Global Budgets for Large Safety-Net Hospital Systems, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (Aug. 16, 2017).

57. Sabatini, Nelson, et al., “Maryland’s All-Payer Model—Achievements, Challenges, And Next Steps,” Health Affairs Blog (July 31, 2017).

58. Cohen, Stephanie, and Erin Butto, Hospital Rate Setting: Promising, but Challenging to Replicate, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Washington, D.C. (August 2017).

59. Pennsylvania Department of Health, Health Innovation in Pennsylvania Plan (June 30, 2016).

60. Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/pa-rural-health-model/ (accessed on Aug. 21, 2017).

61. Mueller, Keith J., et al., After Hospital Closure: Pursuing High Performance Rural Health Systems without Inpatient Care, Rural Policy Research Institute, Iowa City, Iowa (June 2017).

62. Rural Health Information Hub, Intermountain Healthcare TeleHealth Services, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/community-health/project-examples/925 (accessed on Oct. 12, 2017).