Minnesota Survey Respondents Bear Health Care Affordability Burdens Unequally; Distrust of/Disrespect by Health Care Providers Leads Some to Delay/Go Without Needed Care

Key Findings

A survey of more than 1,400 Minnesota adults, conducted from October 31 to November 8, 2023,

found that:

- More than three in five (64%) Minnesota respondents have experienced one or more health care affordability burdens in the past 12 months. Four in five (83%) worry about affording some aspect of health care now or in the future.

- Respondents living in households with a person with a disability more frequently reported affordability burdens compared to respondents without a disabled household member, including rationing medication due to cost (45% versus 21%), delaying or going without care due to cost (74% versus 50%), and going into medical debt, depleting savings or sacrificing basic needs due to medical bills (60% versus 35%).

- Thirty-nine percent of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) respondents skipped needed medical care due to distrust of or feeling disrespected by health care providers, compared to 20% of white alone, non-Hispanic respondents.

- Sixty-one percent of all respondents think that people are treated unfairly based on their race or ethnic background somewhat or very often in the U.S. health care system.

Differences in Health Care Affordability Burdens & Concerns

Race

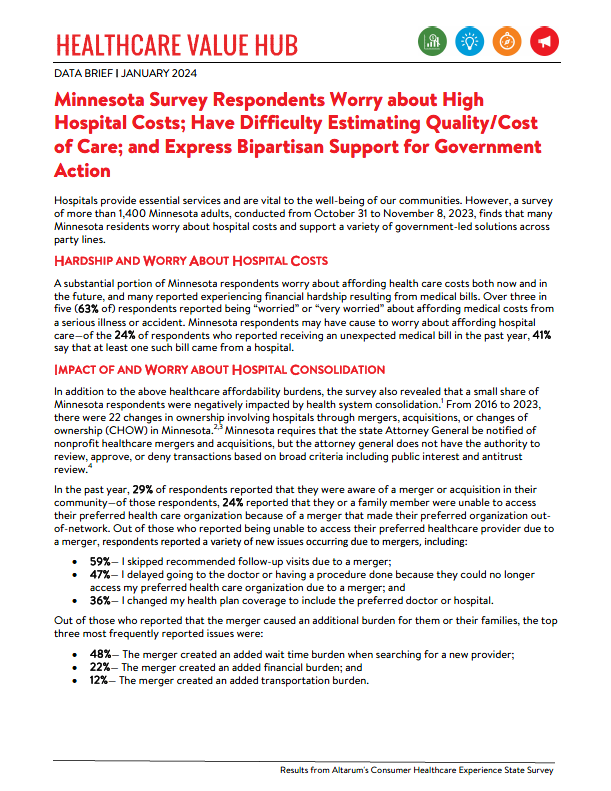

Racial disparities in health care and affordability impact access to care and may contribute to financial

burdens among Black, Indigenous, Hispanic/Latino, and other communities of color.1,2 In Minnesota, BIPOC respondents reported higher rates of all but one affordability burdens than white alone, non-Hispanic/Latino respondents, including incurring medical debt, depleting savings, or sacrificing basic needs (like food, heat and housing) due to medical bills (see Table 1).

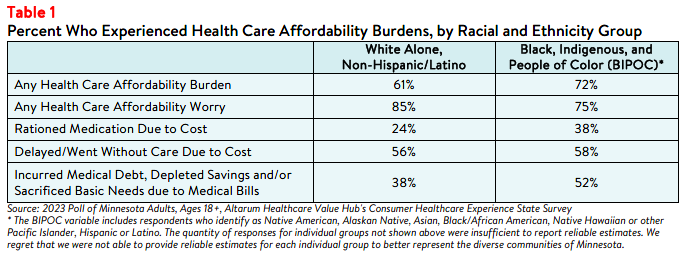

In addition to incurring medical debt, BIPOC respondents more frequently reported difficulty getting

select types of care compared to white, non-Hispanic respondents. For example, BIPOC respondents

more frequently reported challenges accessing addiction treatment, rationing medication, and avoiding

going to the doctor or getting a procedure done to cost (see Figure 1).3

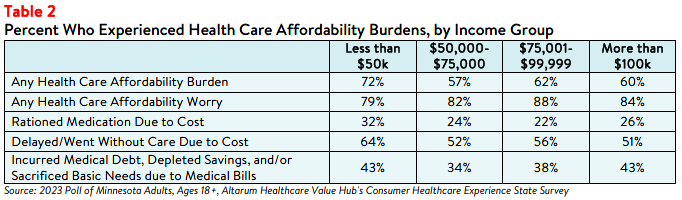

Income

The survey also revealed differences in how Minnesota respondents experience health care affordability

burdens by income. Unsurprisingly, respondents at the lowest end of the income spectrum most

frequently reported affordability burdens, with nearly three-fourths (72%) of those with household

incomes of less than $50,000 per year struggling to afford health care in the past 12 months (see Table

2). Still, over half of respondents living in middle- and high-income households also reported struggling to

afford some aspect of coverage or care, demonstrating that affordability burdens impact people all

income groups. Likewise, at least 79% of respondents in each income group reported being worried about

affording health care either now or in the future.

Additionally, nearly one in three (32% of) respondents with household incomes of $50,000 or less

reported not filling a prescription, skipping doses of medicines, or cutting pills in half due to cost. It is

interesting to note, that both lower-income and higher-income respondents reported financial

consequences after receiving health care services— 43% of respondents in both income groups reported

going into medical debt, depleted their savings, or sacrificed other basic needs (like food, heat or housing)

due to medical bills.

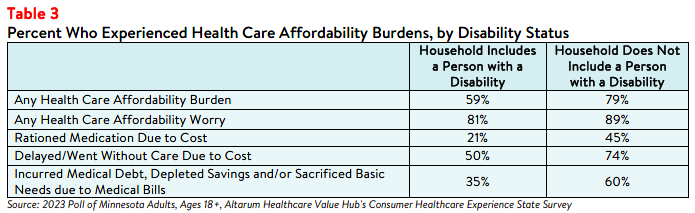

Disabililty Status

People with disabilities interact with the health care system more often than those without disabilities and,

as a result, tend to face more out-of-pocket costs.4 Additionally, people who receive disability benefits

face unique coverage challenges that impact their ability to afford needed care, such as the possibility of

losing coverage if their household income or assets increase over a certain amount (for example, after

getting married).5 Minnesota respondents who have or live with a person who has a disability more

frequently reported a diverse array of affordability burdens compared to others (see Table 3). These

respondents also more frequently reported worrying about future health care affordability in general

(89% versus 81%) and losing health insurance specifically (47% versus 23%).

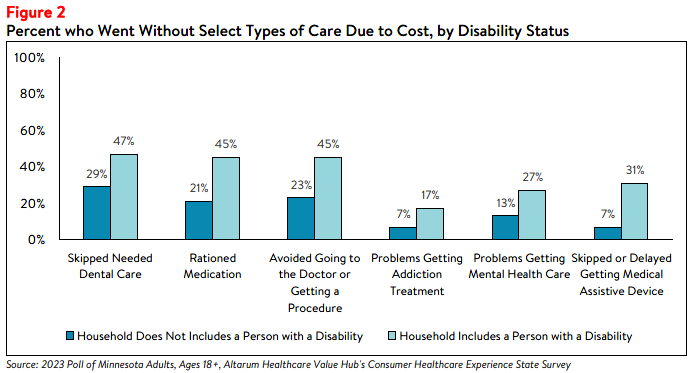

Those with disabilities also face health care affordability burdens unique to their disabilities—31% of

respondents with a disability or a person with a disability in their household reported delaying getting a

medical assistive device such as a wheelchair, cane/walker, hearing aid, or prosthetic limb due to cost. Just 7% of respondents without a disability (who may have needed such tools temporarily or may not identify as having a disability) reported this experience (see Figure 2). Similarly, 27% of respondents with a disability or a person with a disability in their household reported problems getting mental health care

compared to 13% of households without a person with a disability.

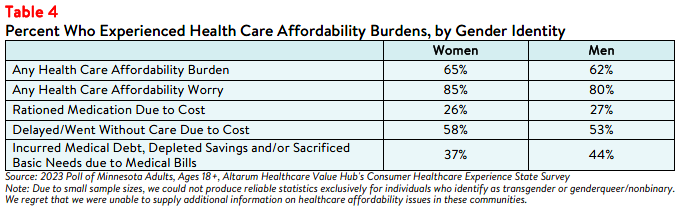

Gender

The survey also surfaced differences in health care affordability burdens and worry by gender. Women

who responded to the survey reported higher rates of experiencing at least one affordability burden in the

past year than those identifying as men (65% versus 62%) (see Table 4). Women also more frequently

reported delaying or going without care due to cost. However, while many respondents regardless of

gender reported being somewhat or very concerned about health care costs, a higher percentage of

women reported worrying about affording some aspect of coverage or care than men (85% versus 80%).

Due to the small sample size, this survey could not produce reliable estimates exclusively for transgender,

genderqueer, or nonbinary respondents. However, it is important to note that these groups experience

unique health care affordability burdens— 25 (2% of) survey respondents reported that they or a family

member had trouble affording the cost of gender-affirming care, such as hormone therapy or

reconstructive surgery.

Distrust and Mistrust in the Health System

Whether a patient trusts and/or feels respected by their health care provider may impact whether they

seek needed care. In Minnesota, nearly one in every four (23% of) respondents reported that their

provider never, rarely, or only sometimes treats them with respect. When asked why they felt health care

providers did not treat them with respect, more than half of the respondents cited their income or

financial status (51%). In slightly fewer numbers, other respondents reported that they felt their health

care provider did not treat them with respect because of their race (32%), ethnic background (28%), and

disability (25%). Respondents also cited gender or gender identity (20%), experience with violence or

abuse (11%), and sexual orientation (8%) as reasons for the disrespect.

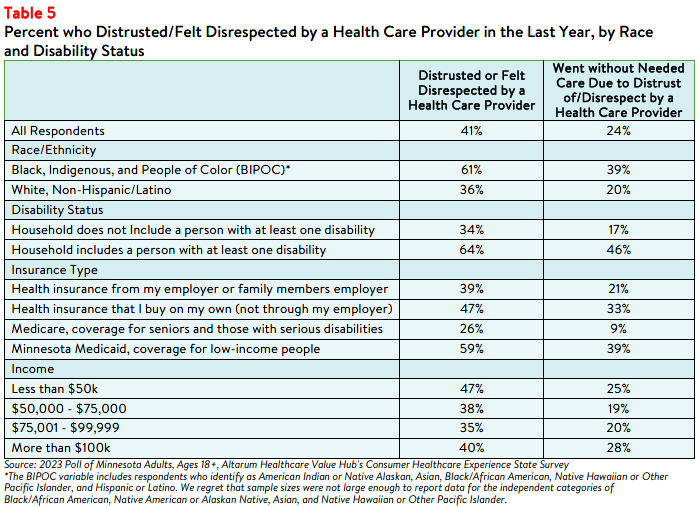

BIPOC respondents and those with a disability or a person with a disability in their household more

frequently reported distrust in and feeling disrespected by their health care providers compared to white

respondents those without a disabled household member (see Table 5). They also more frequently went

without medical care due to that distrust and/or disrespect.

Overall, 39% of BIPOC respondents reported going without needed medical care due to distrust of or

feeling disrespected by health care providers, compared to only 20% of white, non-Hispanic respondents.

Additionally, 46% of respondents who have or are living with a person with a disability went without care

due to distrust or disrespect, compared to 17% of those without a household member with a disability.

Respondents covered through Minnesota Medicaid reported the highest rates of distrusting or feeling

disrespected by a health care provider compared to other insurance types. In addition, respondents

earning less than $50,000 most frequently reported feeling distrusted or disrespected by their health

care provider. However, respondents in the highest income category most frequently reported going

without care due to distrust/disrespect (28%).

Individual & Systemic Racism

Respondents perceived that both individual and systemic racism exist in the U.S. health care system. Fifty-seven percent of respondents believe that people are treated unfairly based on their race or ethnic

background, either somewhat or very often. When asked what they think causes healthcare systems to

treat people unfairly based on their race or ethnic background:

- 1 in 5 (21%) cited policies and practices built into the health care system;

- Greater than 1 in 10 (16%) cited the actions and beliefs of individual health care providers; and

- 2 in 5 (42%) believe it is an equal mixture of both.

Dissatisfaction with the Health System & Support for Change

Given this information, it is not surprising that 74% of Minnesota respondents agree or strongly agree that

the U.S. health care system needs to change. Understanding how the health care system

disproportionately harms some groups of people over others is key to creating a fairer and higher value

system for all.

Making health care affordable for all residents is an area ripe for policymaker intervention, with

widespread support for government-led solutions across party lines. For more information on the types of

strategies Minnesota residents want their policymakers to pursue, see: Minnesota Residents Struggle to

Afford High Healthcare Costs; Worry about Affording Healthcare in the Future; Support Government Action across Party Lines, Healthcare Value Hub (January 2024).

Notes

- Fadeyi-Jones, Tomi, et al., High Prescription Drug Prices Perpetuate Systemic Racism. We Can Change It, Patients for Affordable Drugs Now (December 2020), https://patientsforaffordabledrugsnow.org/2020/12/14/drug-pricing-systemic-racism/

- Kaplan, Alan and O’Neill, Daniel, “Hospital Price Discrimination Is Deepening Racial Health Inequity,” New England Journal of Medicine—Catalyst (December 2020), https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0593

- A small share of respondents also reported barriers to care that were unique to their ethnic or cultural backgrounds. Three percent reported not getting needed medical care because they couldn’t find a doctor of the same race, ethnicity or cultural background as them and three percent because they couldn’t find a doctor who spoke their language.

- Miles, Angel L., Challenges and Opportunities in Quality Affordable Health Care Coverage for People with Disabilities, Protect Our Care Illinois (February 2021), https://protectourcareil.org/index.php/2021/02/26/challenges-and-

opportunities-in-quality-affordable-health-care-coverage-for-people-with-disabilities/ - A 2019 Commonwealth Fund report noted that people with disabilities risk losing their benefits if they make more than $1,000 per month. According to the Center for American Progress, in most states, people who receive Supplemental Security are automatically eligible for Medicaid. Therefore, if they lose their disability benefits they may also lose their Medicaid coverage. Forbes has also reported on marriage penalties for people with disabilities, including fears about losing health insurance. See: Seervai, Shanoor, Shah, Arnav, and Shah, Tanya, “The Challenges of Living with a Disability in America, and How Serious Illness Can Add to Them,” Commonwealth Fund (April 2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2019/apr/challenges-living-disability-america-and-how-serious-illness-can; Fremstaf, Shawn and Valles, Rebecca, “The Facts on Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income for Workers with Disabilities,” Center for American Progress (May 2013),

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-facts-on-social-security-disability-insurance-and-supplemental-security-income-for-workers-with-disabilities/; and Pulrang, Andrew, “A Simple Fix For One Of Disabled People’s Most Persistent, Pointless Injustices,” Forbes (April 2020), https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2020/08/31/a-simple-fix-for-one-of-disabled-peoples-most-persistent-pointless-injustices/?sh=6e159b946b7

Methodology

Altarum’s Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) is designed to elicit respondents’ unbiased views on a wide range of health system issues, including confidence using the health system, financial burden and possible policy solutions.

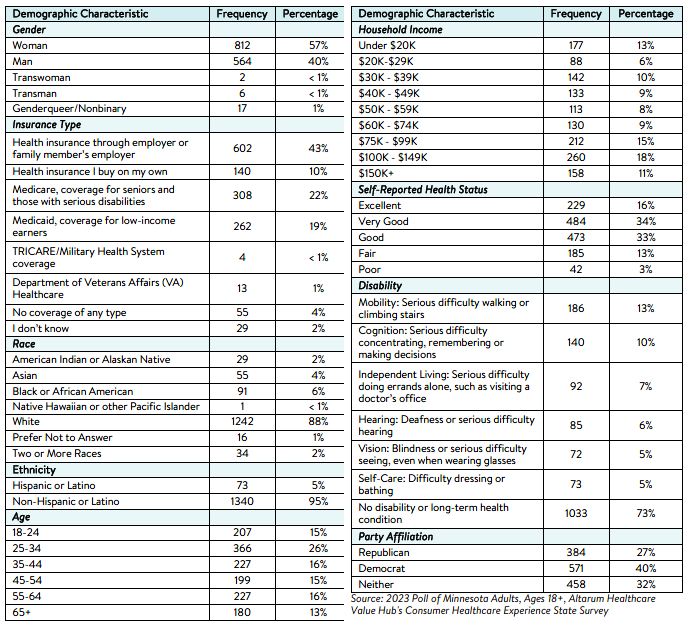

This survey, conducted from October 31 to November 8, 2023, used a web panel from online survey company Dynata with a demographically balanced sample of approximately 1,400 respondents who live in Minnesota. Information about Dynata’s recruitment and compensation methods can be found here. The survey was conducted in English or Spanish and restricted to adults ages 18 and older. Respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median time were excluded from the final sample, leaving 1,413 cases for analysis. After those exclusions, the demographic composition of respondents was as follows,

although not all demographic information has complete response rates: