Minnesota Survey Respondents Worry about High Hospital Costs; Have Difficulty Estimating Quality/Cost of Care; and Express Bipartisan Support for Government Action

Hospitals provide essential services and are vital to the well-being of our communities. However, a survey

of more than 1,400 Minnesota adults, conducted from October 31 to November 8, 2023, finds that many

Minnesota residents worry about hospital costs and support a variety of government-led solutions across

party lines.

Hardship and Worry about Hospital Costs

A substantial portion of Minnesota respondents worry about affording health care costs both now and in

the future, and many reported experiencing financial hardship resulting from medical bills. Over three in

five (63% of) respondents reported being “worried” or “very worried” about affording medical costs from

a serious illness or accident. Minnesota respondents may have cause to worry about affording hospital

care—of the 24% of respondents who reported receiving an unexpected medical bill in the past year, 41%

say that at least one such bill came from a hospital.

Impact and Worry About Hospital Consolidation

In addition to the above healthcare affordability burdens, the survey also revealed that a small share of

Minnesota respondents were negatively impacted by health system consolidation.1

From 2016 to 2023, there were 22 changes in ownership involving hospitals through mergers, acquisitions, or changes of ownership (CHOW) in Minnesota.2,3 Minnesota requires that the state Attorney General be notified of nonprofit healthcare mergers and acquisitions, but the attorney general does not have the authority to review, approve, or deny transactions based on broad criteria including public interest and antitrust review.4

In the past year, 29% of respondents reported that they were aware of a merger or acquisition in their

community—of those respondents, 24% reported that they or a family member were unable to access

their preferred health care organization because of a merger that made their preferred organization out-

of-network. Out of those who reported being unable to access their preferred healthcare provider due to

a merger, respondents reported a variety of new issues occurring due to mergers, including:

- 59%— I skipped recommended follow-up visits due to a merger;

- 47%— I delayed going to the doctor or having a procedure done because they could no longer access my preferred health care organization due to a merger; and

- 36%— I changed my health plan coverage to include the preferred doctor or hospital.

Out of those who reported that the merger caused an additional burden for them or their families, the top

three most frequently reported issues were:

- 48%— The merger created an added wait time burden when searching for a new provider;

- 22%— The merger created an added financial burden; and

- 12%— The merger created an added transportation burden.

While a small portion of respondents reported being unable to access their preferred health care

organization because of a merger, far more respondents (57%) reported that they would be somewhat,

moderately or very worried about the impacts of mergers in their health care organizations if they were to

occur. When asked about their largest concern, respondents most frequently reported:

- 26%— I’m concerned I will have to pay more to see my doctor;

- 24%— I’m concerned my doctor may no longer be covered by my insurance;

- 23%— I’m concerned I will have fewer choices of where to receive care;

- 15%—I’m concerned I will have to travel farther to see my doctor; and

- 12%—I’m concerned I will have a lower quality of care.

Survey respondents were also asked to share their challenges following hospital consolidation. Selected

responses highlighting some of these burdens are listed below.

Skills Navigating Hospital Care

Minnesota respondents reported moderately high confidence in their ability to know when to seek

emergency care, with 66% reporting that they are very or extremely confident about knowing when to go

to the emergency department versus a primary care provider. However, they are less confident in their

ability to find hospital costs and quality information. Fifty-five percent of respondents reported that they

are not confident that they can find out the cost of a procedure ahead of time, and half of respondents

are not confident that they would be able to find quality rankings for hospitals (50%) or doctors (51%)

should they need that information.

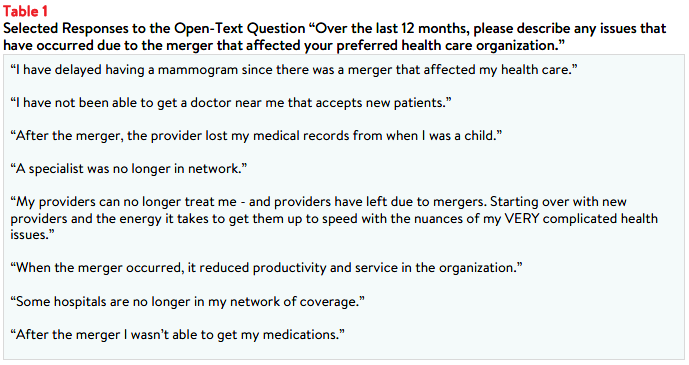

Minnesota respondents’ lack of confidence may be reflected in the low rates of searching for hospital

price and quality information. Out of all respondents, only 29% tried to find the out-of-pocket cost of a

hospital stay in the past twelve months, and 12% of all respondents reported needing to stay in the

hospital, but not searching for cost information ahead of time. Out of those respondents who reported

either trying to find hospital cost information or needing a hospital stay, 47% reported successfully finding

sufficient cost information, 23% reported they did not find sufficient cost information, and 30% did not

attempt to find cost information when they needed a hospital stay.

Similarly, 34% of all respondents reported that they tried to find hospital quality information in the past

twelve months, and 17% of reported needing to stay in a hospital but not looking for quality information

ahead of time. However, out of those respondents who tried to find hospital quality information or

needed a hospital stay, 45% reported successfully finding sufficient quality information, 22% reported

that they were unable to find sufficient quality information, and 33% did not attempt to find quality

information when they needed a hospital. Similar trends were observed when respondents were asked

about their success finding the cost for primary care doctor visits, specialist visits, and medical tests (see

Figure 1).

Among respondents who needed a service but did not attempt to discover price or quality information

ahead of time, the most frequently reported reasons for not seeking the information include:

- 34%— Respondents followed their doctors’ recommendations or referrals;

- 32%— Respondents did not know where to look;

- 28%— Respondents felt that looking for information was confusing or overwhelming;

- 20%— Respondents reported that it never occurred to them to look for quality rankings or price information; and

- 19%— Respondents did not have time to look.

Notably, few of these respondents reported that the out-of-pocket cost or quality were unimportant to

them (14% and 6%, respectively).

Although many of the respondents who reported searching for cost and quality information were

ultimately able to find that information, there were respondents who were unsuccessful in their attempts.

Respondents who were unsuccessful reported a variety common barriers to finding cost and/or quality

information for needed health services, such as:

- 47%— The resources available to search for price information were confusing;

- 42%— Their provider, hospital, or pharmacist would not give them a price estimate;

- 39%— Their insurance plan would not give them a price estimate;

- 29%— The resources available to search for quality information were confusing;

- 26%— The price information was insufficient; and

- 18%— The quality information available was not sufficient.

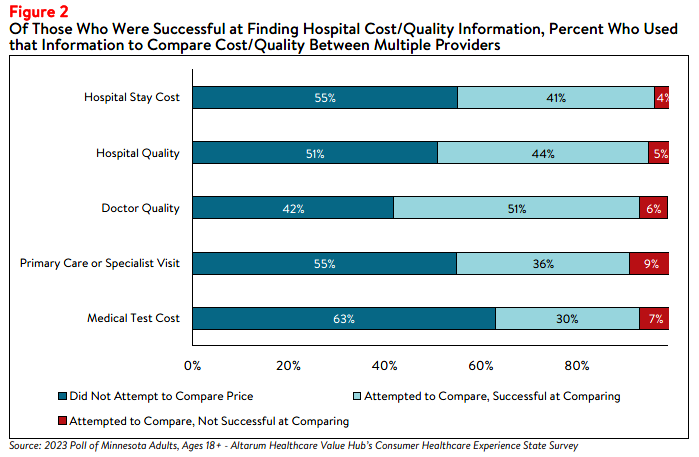

Among those who were successful at finding hospital cost or quality information, a little over half

reported that they did not use this information to compare prices (55%) or quality (51%) between

hospitals (i.e. “shopping”). Respondents identified a variety of reasons they did not compare cost and

quality information across multiple providers; including only wanting to know how much the service would

cost with their chosen provider (32%), choosing to follow their doctors’ recommendations (31%), and not

having time to compare prices across multiple providers (24%). These reasons could also be influenced by this information not being accessible, despite federal price transparency mandates for hospitals.5

It could also stem from the fact that some consumers don’t view health care as a shoppable commodity,

especially in emergency situations and settings that lack a selection of treatments or providers. However,

a lack of knowledge of hospital quality and potential costs may impede Minnesota residents’ ability to plan

for needed care and budget for the expense of a hospital stay, which can be costly, particularly for

residents who are uninsured or under-insured.6

However, the respondents who did attempt to compare the out-of-pocket cost for a hospital stay or

hospital quality information (45% and 49%, respectively) reported being relatively successful in their

attempts. Ninety-one percent of those who attempted to compare the out-of-pocket costs for a hospital

stay reported finding enough information to successfully compare prices. Similarly, 89% of respondents

who were able to find sufficient hospital quality information reported using that information to compare

the quality of two or more hospitals (see Figure 2).

Among those that did compare cost or quality information for different services, many reported that the

cost or quality comparison ultimately influenced their choice of which provider to seek care from.

Seventy-six percent of those who compared primary care or specialist doctor visit costs said the

comparison influenced their choice, as did 85% of those who compared medical test costs, and 87% of

those who compared hospital stay costs. Among those who looked for hospital quality information, 88%

had their choice influenced by the information.

Support for Action Across Party Lines

Hospitals, along with drug manufacturers and insurance companies, are viewed as a primary contributor to

high health care costs. When given more than 20 options, those that Minnesota respondents most

frequently cited as being a “major reason” for high health care costs were:

- 78%— Drug companies charging too much money;

- 71%— Hospitals charging too much money;

- 68%— Insurance companies charging too much money; and

- 57%— Large hospitals or doctor groups using their influence to get higher payments from insurance companies.

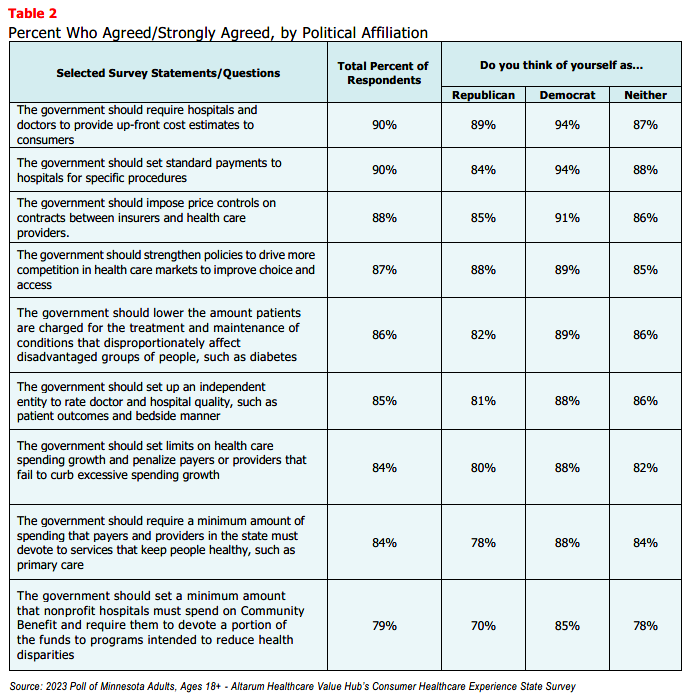

When asked, Minnesota respondents strongly endorsed several hospital-related strategies, including:

- 90%— Require hospitals and doctors to provide up-front cost estimates to consumers;

- 90%— Set standard payments to hospitals for specific procedures;

- 88%— Impose price controls on contracts between insurers and health care providers;

- 87%— Strengthen policies to drive more competition in health care;

- 86%— Lower the amount patients are charged for the treatment and maintenance of conditions that disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups of people, such as diabetes; and

- 85%— Set up an independent entity to rate doctor and hospital quality, such as patient outcomes;

What’s even more interesting is the level of support for some of these strategies across party lines (see

Table 2).

Conclusion

The findings from this poll suggest that Minnesota respondents are somewhat motivated when it comes to

searching for hospital cost and quality information to help inform purchasing decisions and plan for a

future medical expense. Still, over half did not search for this information at all, suggesting that effort to

influence consumer shopping through price transparency initiatives may not be effective for everyone.

It is not surprising that Minnesota respondents express strong support for government-led solutions to

make price and quality information more readily accessible and to help consumers navigate hospital care.

Many of the solutions that respondent’s support would take the burden of research and guesswork off

consumers, such as standardizing payments for specific hospital procedures, requiring hospitals and

doctors to provide consumers cost estimates for certain procedures, and establishing an entity to conduct

independent quality reviews. Policymakers should investigate the evidence on these and other policy

options to respond to respondents’ bipartisan call for government action.

Notes

-

The sample size of respondents who said they were affected by a merger was not large enough to report reliable

estimates, so the values in this section should be interpreted with caution. -

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2023). Hospital Change of Ownership. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from https://data.cms.gov/provider-characteristics/hospitals-and-other-facilities/hospital-change-of-ownership.

-

A CHOW typically occurs when a Medicare provider has been purchased (or leased) by another organization. The CHOW results in the transfer of the old owner's identification number and provider agreement (including any Medicare outstanding debt of the old owner) to the new owner…An acquisition/merger occurs when a currently enrolled Medicare provider is purchasing or has been purchased by another enrolled provider. Only the purchaser's CMS Certification Number (CCN) and tax identification number remain. Acquisitions/mergers are different from CHOWs. In the case of an acquisition/merger, the seller/former owner's CCN dissolves. In a CHOW, the seller/former owner's CCN typically remains intact and is transferred to the new owner. A consolidation occurs when two or more enrolled Medicare providers consolidate to form a new business entity. Consolidations are different from acquisitions/mergers. In an acquisition/merger, two entities combine but the CCN and tax identification number (TIN) of the purchasing entity remains intact. In a consolidation, the TINs and CCN of the consolidating entities dissolve and a new TIN and CCN are assigned to the new, consolidated entity. Source: Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Change of Ownership Guidelines—Medicare/State Certified Hospice. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from

https://health.mo.gov/safety/homecare/pdf/CHOW-Guidelines-

StateLicensedHospice.pdf#:~:text=Acquisitions%2Fmergers%20are %20different%20from%20CHOWs.%20In%20the%2

0case,providers%20consolidate%20to%20form%20a%20new%20business%20entity. -

The Source on Healthcare Price and Competition, Merger Review, Retrieved December 8, 2023 from

https://sourceonhealthcare.org/market-consolidation/merger-review/ -

As of January 1, 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires hospitals to make public a

machine-readable file containing a list of standard charges for all items and services provided by the hospital, as well as a consumer-friendly display of at least 300 shoppable services that a patient can schedule in advance. However, Compliance from hospitals has been mixed, indicating that the rule has yet to demonstrate the desired effect. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/hospital-price-transparency-progress-and-commitment-achieving-its-potential -

According to Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, hospital adjusted expenses per inpatient day in Minnesota were $2,561 in 2021, which is slightly lower than the national average. See: Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts Data: Hospital Adjusted Expenses per Inpatient Day. Accessed December 8, 2023. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day/

Methodology

Altarum’s Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) is designed to elicit respondents’ unbiased views on a wide range of health system issues, including confidence using the health system, financial burden and possible policy solutions.

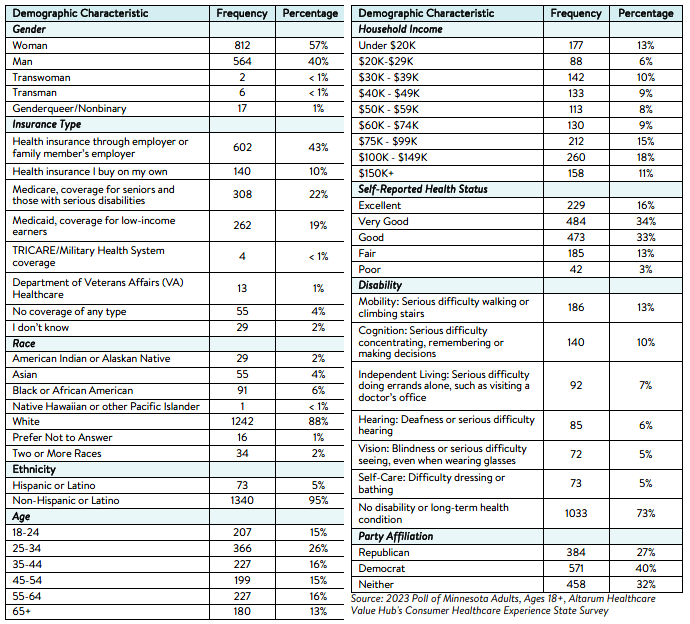

This survey, conducted from October 31 to November 8, 2023, used a web panel from online survey company Dynata with a demographically balanced sample of approximately 1,400 respondents who live in Minnesota. Information about Dynata’s recruitment and compensation methods can be found here. The survey was conducted in English or Spanish and restricted to adults ages 18 and older. Respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median time were excluded from the final sample, leaving 1,413 cases for analysis. After those exclusions, the demographic composition of respondents was as follows,

although not all demographic information has complete response rates: