North Carolina Survey Respondents Worried about High Drug Costs; Support a Range of Government Solutions

According to a survey of more than 1,400 North Carolina adults, conducted from October 18 to October

23, 2023, respondents are concerned about prescription drug costs and express a strong desire for

policymakers to enact solutions.

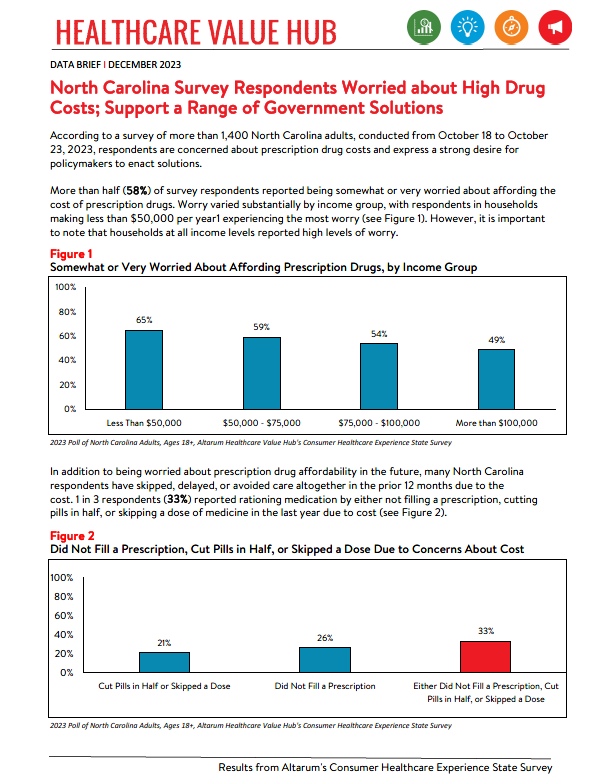

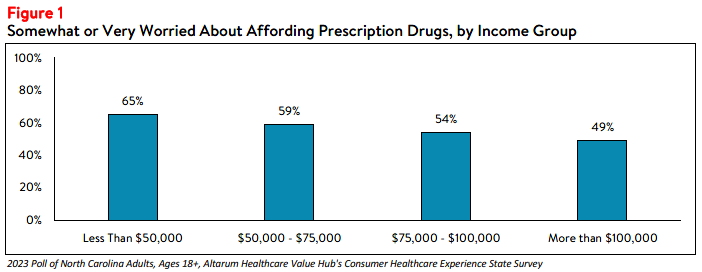

More than half (58%) of survey respondents reported being somewhat or very worried about affording the

cost of prescription drugs. Worry varied substantially by income group, with respondents in households

making less than $50,000 per year1 experiencing the most worry (see Figure 1). However, it is important

to note that households at all income levels reported high levels of worry.

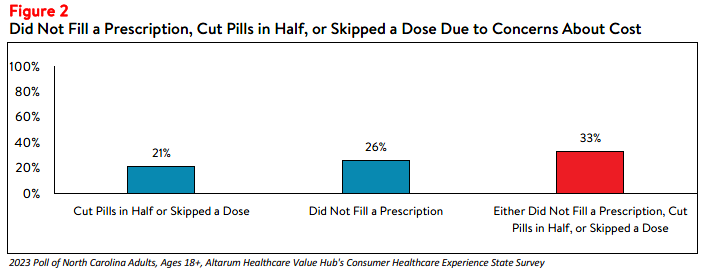

In addition to being worried about prescription drug affordability in the future, many North Carolina

respondents have skipped, delayed, or avoided care altogether in the prior 12 months due to the

cost. 1 in 3 respondents (33%) reported rationing medication by either not filling a prescription, cutting

pills in half, or skipping a dose of medicine in the last year due to cost (see Figure 2).

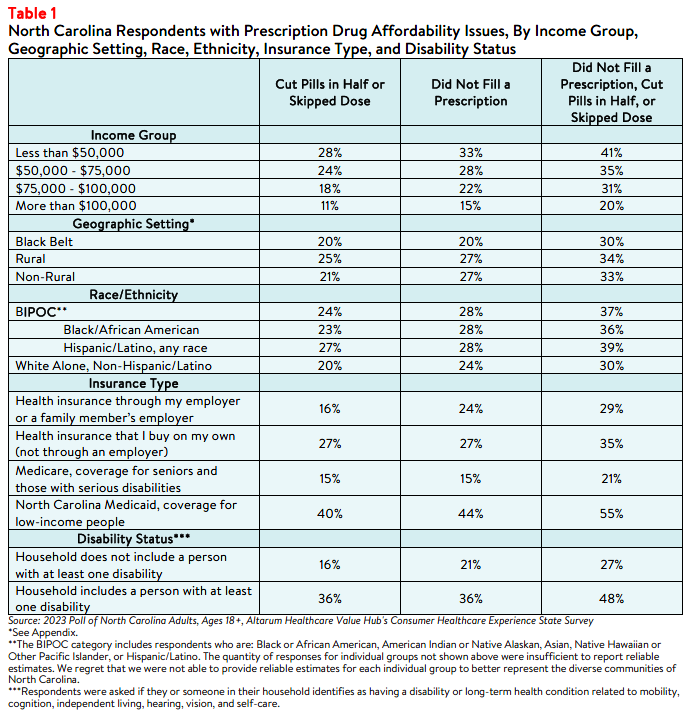

These hardships disproportionately impact people in lower-income households. As Table 1 shows,

respondents living in households earning less than $50,000 and those earning between $50,000 and

$75,000 per year reported higher rates of rationing their prescription medicines than respondents living in

higher-income households. However, these hardships are alarmingly prevalent in middle-income

households as well.

Respondents with North Carolina Medicaid coverage reported the highest rates of rationing medication

compared to other insurance types, followed by those with private insurance. Finally, respondents living in

households with a person with a disability reported notably higher rates of rationing medication due to cost in the past 12 months compared to respondents without a disabled household member (see Table 1).

Considering these prescription drug cost concerns—as well as concerns about high healthcare costs

generally2—it is not surprising that North Carolina respondents were generally dissatisfied with the health

system:

- Just 30% agreed or strongly agreed that “we have a great healthcare system in the U.S.,”

- While 75% agreed or strongly agreed that “the system needs to change.”

North Carolina respondents see a role for themselves in addressing prescription drug affordability. When

asked about specific actions they could take:

- 59% of respondents reported researching the cost of a drug beforehand, and

- 80% said they would be willing to switch from a brand name to an equivalent generic drug if given the chance.

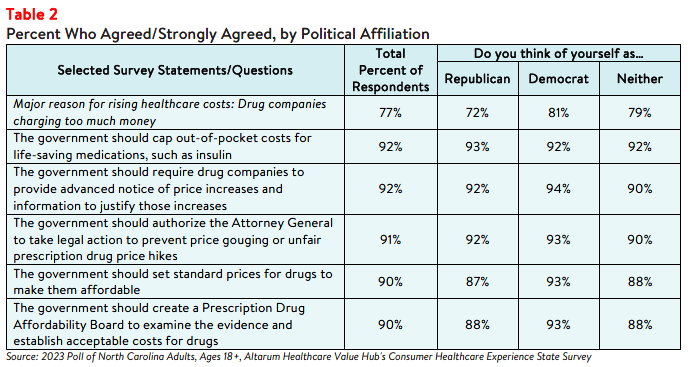

When given more than 20 options, the options cited most frequently as being a "major reason" for high

healthcare costs were:

- 77%—Drug companies charging too much money

- 73%—Hospitals charging too much money

- 70%—Insurance companies charging too much money

When it comes to tackling high drug costs, North Carolina respondents endorsed a number of prescription

drug-related strategies:

- 92%—Cap out-of-pocket costs for life-saving medications, such as insulin

- 92%—Require drug companies to provide advanced notice of price increases and information to justify those increases

- 91%—Authorize the Attorney General to take legal action to prevent price gouging or unfair prescription drug price hikes

- 90%—Set standard prices for drugs to make them affordable

- 90%—Create a Prescription Drug Affordability Board to examine the evidence and establish acceptable costs for drugs

- 89%—Prohibit drug companies from charging more in the U.S. than abroad

Moreover, there is substantial support for government action on drug costs regardless of the respondent’s

political affiliation (see Table 2).

Conclusion

The high burden of healthcare and prescription drug affordability, along with high levels of support for

change, suggests that elected leaders and other stakeholders need to make addressing this consumer

burden a top priority. Moreover, the COVID crisis has led state residents to take a hard look at how well

health and public health systems are working for them, with strong support for a wide variety of actions.

Annual surveys can help assess whether progress is being made.

Notes

-

Median household income in North Carolina was $60,516 (2017-2021). U.S. Census, Quick Facts. Retrieved from: U.S.Census Bureau QuickFacts

-

For more detailed information about healthcare affordability burdens facing North Carolina respondents, please see Healthcare Value Hub, North Carolina Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Worry About Affording Healthcare in the Future; Support Government Action across Party Lines, Data Brief (December 2023).

Methodology

Altarum’s Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) is designed to elicit respondents’ unbiased views on a wide range of health system issues, including confidence using the health system, financial burden and possible policy solutions.

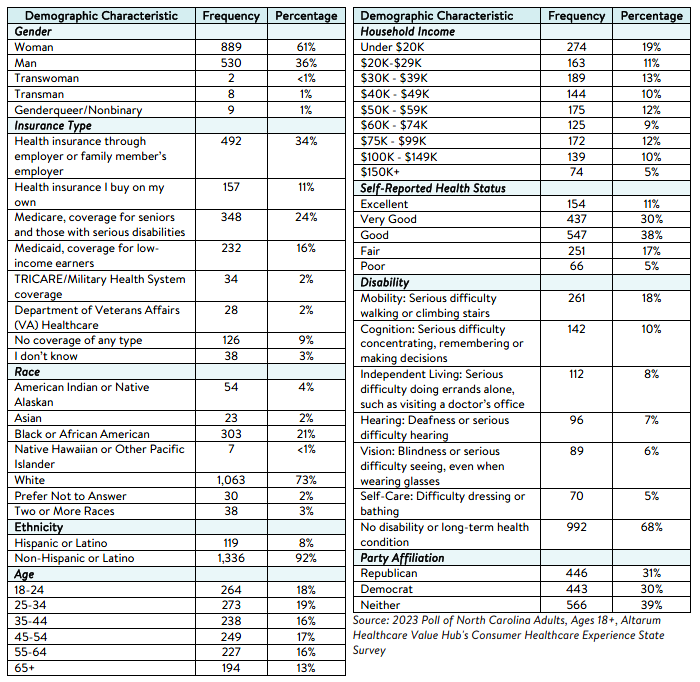

This survey, conducted from October 18 to October 23, 2023, used a web panel from online survey company Dynata with a demographically balanced sample of approximately 1,500 respondents who live in North Carolina. Information about Dynata’s recruitment and compensation methods can be found here. The survey was conducted in English or Spanish and restricted to adults ages 18 and older. Respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median time were excluded from the final sample, leaving 1,455 cases for analysis. After those exclusions, the demographic composition of respondents was as follows, although not all demographic information has complete response rates:

variance more than 0.30.

Appendix

|

Black Belt |

Non-Rural |

Rural |

|

Anson County, North Carolina |

Alamance County, North Carolina |

Alleghany County, North Carolina |

|

Bertie County, North Carolina |

Alexander County, North Carolina |

Ashe County, North Carolina |

|

Bladen County, North Carolina |

Brunswick County, North Carolina |

Avery County, North Carolina |

|

Columbus County, North Carolina |

Buncombe County, North Carolina |

Beaufort County, North Carolina |

|

Cumberland County, North Carolina |

Burke County, North Carolina |

Camden County, North Carolina |

|

Duplin County, North Carolina |

Cabarrus County, North Carolina |

Carteret County, North Carolina |

|

Edgecombe County, North Carolina |

Caldwell County, North Carolina |

Caswell County, North Carolina |

|

Franklin County, North Carolina |

Catawba County, North Carolina |

Cherokee County, North Carolina |

|

Gates County, North Carolina |

Chatham County, North Carolina |

Chowan County, North Carolina |

|

Granville County, North Carolina |

Craven County, North Carolina |

Clay County, North Carolina |

|

Greene County, North Carolina |

Currituck County, North Carolina |

Cleveland County, North Carolina |

|

Halifax County, North Carolina |

Davidson County, North Carolina |

Dare County, North Carolina |

|

Hertford County, North Carolina |

Davie County, North Carolina |

Graham County, North Carolina |

|

Hoke County, North Carolina |

Durham County, North Carolina |

Harnett County, North Carolina |

|

Lenoir County, North Carolina |

Forsyth County, North Carolina |

Hyde County, North Carolina |

|

Martin County, North Carolina |

Gaston County, North Carolina |

Jackson County, North Carolina |

|

Nash County, North Carolina |

Guilford County, North Carolina |

Lee County, North Carolina |

|

Northampton County, North Carolina |

Haywood County, North Carolina |

McDowell County, North Carolina |

|

Pitt County, North Carolina |

Henderson County, North Carolina |

Macon County, North Carolina |

|

Richmond County, North Carolina |

Iredell County, North Carolina |

Mitchell County, North Carolina |

|

Robeson County, North Carolina |

Johnston County, North Carolina |

Montgomery County, North Carolina |

|

Sampson County, North Carolina |

Jones County, North Carolina |

Moore County, North Carolina |

|

Scotland County, North Carolina |

Lincoln County, North Carolina |

Pasquotank County, North Carolina |

|

Tyrrell County, North Carolina |

Madison County, North Carolina |

Perquimans County, North Carolina |

|

Vance County, North Carolina |

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina |

Polk County, North Carolina |

|

Warren County, North Carolina |

New Hanover County, North Carolina |

Rutherford County, North Carolina |

|

Washington County, North Carolina |

Onslow County, North Carolina |

Stanly County, North Carolina |

|

Wayne County, North Carolina |

Orange County, North Carolina |

Surry County, North Carolina |

|

Wilson County, North Carolina |

Pamlico County, North Carolina |

Swain County, North Carolina |

|

Pender County, North Carolina |

Transylvania County, North Carolina |

|

|

Person County, North Carolina |

Watauga County, North Carolina |

|

|

Randolph County, North Carolina |

Wilkes County, North Carolina |

|

|

Rockingham County, North Carolina |

Yancey County, North Carolina |

|

|

|

Rowan County, North Carolina |

|

|

|

Stokes County, North Carolina |

|

|

|

Union County, North Carolina |

|

|

|

Wake County, North Carolina |

|

|

|

Yadkin County, North Carolina |

|