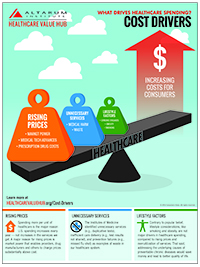

Cost Drivers

What Drives Health Care Spending?

For decades, health care costs have risen faster than the general rate of inflation. What's more, there is strong evidence that we aren't getting good value for the money we spend.

Discussions of high and rising health care costs aren’t just an academic exercise—health care costs are an urgent problem and have a profound impact on the health and financial security of American families. The following sections identify drivers of U.S. health care spending to inform efforts to find solutions.

Rising Unit Prices

Evidence is clear that rising U.S. health care spending is driven by increases in the unit prices of health care services—not increases in the number of services Americans receive.1 A major contributor to rising unit prices is market power that enables providers, drug manufacturers and others to charge prices substantially above the cost of production.

Consolidation

Health care organizations typically argue that mergers improve efficiency and create economies-of-scale, improving quality and reducing costs. Yet little reliable evidence supports this claim. In fact, a growing body research demonstrates that mergers (between organizations in the same and different markets) increase health care prices by as much as 44 percent with no evidence of quality improvement.2,3

Advances in Medical Technology

Due to successful marketing and other factors, expensive medical technology is sometimes used in clinical settings without evidence of cost-effectiveness. This drives up health care costs without benefitting patients. [Learn more!]

Prescription Drug Costs

The U.S. prescription drug market is complex and, for a variety of reasons, lacks the competitive forces that help regulate prices in other sectors of the economy. Barriers to competition include patent protection, market exclusivity and natural monopolies for drugs treating diseases with patient populations that are too small to attract multiple manufacturers. All of these factors, in addition to more controversial practices, have contributed to a 25 percent increase in the unit prices of prescription drugs from 2013-2017.4 [Learn more!]

Unnecessary Services & Medical Harm

Unnecessary Services

Estimates suggest that overtreatment or low-value care totals $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion per year— this is spending that does not improve patients' health outcomes.5 Despite widespread agreement that low-value services should be eliminated, variation in the benefits of a particular intervention for different patients under different circumstances makes it difficult to definitively identify (and address) low-value care. Other barriers include long-held patterns of clinical practice and financial incentives (like fee-for-service payments) that make providers resistant to change. [Learn more!]

Medical Harm

Perhaps the most egregious form of health care waste is services and procedures that cause patients bodily harm. While the full extent of the problem is unknown, estimates suggest that medical harm may be the third-leading cause of death in the U.S.

As of 2019, there have been no comprehensive assessments of the costs that medical errors add to our nation’s health care bill. Existing studies are limited to the cost of a specific type of adverse event or a particular population. What we do know, however, is that the resources spent on preventing medical harm—by health care providers and governmental agencies—are dwarfed by the resources spent to remedy harm after it occurs. [Learn more!]

Social Determinants of Health

Social Determinants of Health

Research shows that social determinants of health – like safe housing, access to healthy foods and transportation – are responsible for 50 percent of an individual's health status, while clinical care drives only 20 percent.6 Low-income, communities of color are particularly disadvantaged when it comes to social determinants of health, contributing to significant and persistent health disparities within the U.S. A 2018 report by Altarum and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation estimated that U.S. spends $93 billion in excess medical care costs per year as a result of health disparities. [Learn more!]

Personal Determinants of Health

Contrary to popular belief, lifestyle factors like smoking and obesity are minor drivers of health care spending compared to rising unit prices and overutilization of services. Although chronic conditions that can develop from poor lifestyle choices account for a large share of U.S. health spending, the bulk of spending increases are driven by rising prices for the services associated with treating these conditions–not increasing prevalence of disease. That said, addressing the underlying causes of preventable chronic conditions would save money and lead to better quality of life. [Learn more!]

Finally, strong evidence demonstrates that the overall aging of the U.S. population is a minor driver of health care cost growth, contributing only half a percentage point to overall health care spending growth, which averages 5-7% per year.7

Notes

1. Health Care Cost Institute, "2017 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report," Washington, D.C. (February 2019).

2. Webinar: Hospital Competition and Hospital Mergers: What the Best Evidence Tells Us (Sept. 4, 2019). See: https://register.gotowebinar.com/recording/9105625737944442381. See also: https://tobin.yale.edu/news/webinar-hospital-mergers-nonpartisan-research-experts

3. Sutter’s prices increased between 28% and 44% following its merger with Alta Bates. See: Tenn, Steven, “The Price Effects of Hospital Mergers: A Case Study of the Sutter–Summit Transaction,” International Journal of the Economics of Business, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb. 2011).

4. Health Care Cost Institute (February 2019).

5. Shrank, William H., Teresa L Roasted and Natasha Parekh, "Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings," JAMA, Vol. 322, No. 15 (October 7, 2019).

6. Magnan, Sanne, "Social Determinants of Health 101 for Health Care: Five Plus Five," National Academy of Medicine, Washington, D.C. (Oct. 9, 2017).

7. Ewe E. Reinhardt, "Does the Aging of the Population Really Drive the Demand for Health Care?" Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 6 (2003). See also: Yamamoto, Dale H., "Care Costs -- From Birth to Death," Health Care Cost Institute, Washington, D.C. (June 2013).