Missouri Residents Experience Difficulty Estimating the Cost and Quality of Care; Express Bipartisan Support for Government Action

A survey of more than 1,100 Missouri adults, conducted from April 1 to April 18, 2022, explored Missouri residents’ experiences with and opinions about healthcare price and quality information.1,2 This data brief presents findings on respondents’ ability to navigate price and quality information; views on the tradeoffs between healthcare prices and quality; and support for transparency-related policy strategies across party lines.

Difficulty Determining the Cost of Care

Roughly half (51%) of Missouri respondents were “very” or “extremely” confident they could find the price of a healthcare service ahead of time. A higher 74% of respondents report seeking the price of a healthcare service in the prior 12 months.

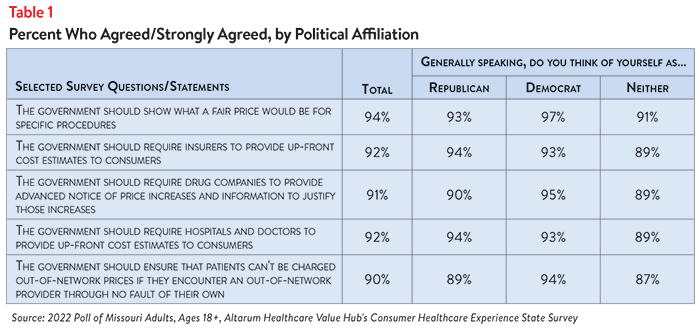

When searching for price information, more than half attempted to determine the out-of-pocket cost for a prescription drug (59%) and/or dental care (51%) (see Figure 1). Respondents less frequently attempted to determine the price of primary care (43%), specialist appointments (42%) and medical tests (41%), and were least likely to search for the price of a hospital stay (32%) and home healthcare services (30%). Still, nearly 1 in 3 sought hospital or home care pricing information.

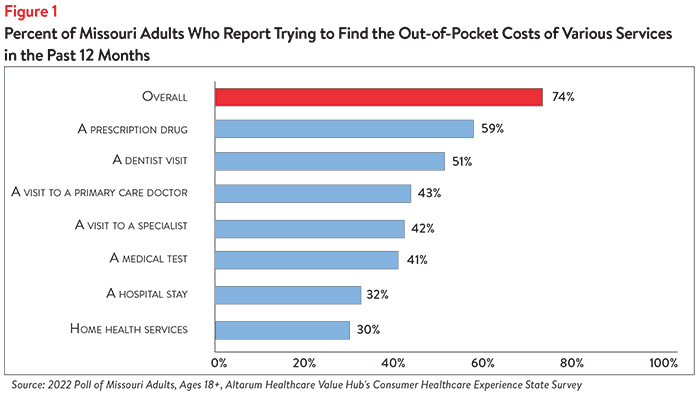

Further analysis shows that, among those who sought price information, the majority were successful (see Figure 2). Prescription drug costs, the most searched for of all service options provided, had the highest success rate, with 83% of respondents who tried to find this information reporting success. Success rates were lower for more complex services. Among those who tried to find the price of a hospital stay, 36% were unsuccessful.

Of those who reported seeking prices to compare two or more healthcare providers, 80% were successful.

Difficulty Determining the Quality of Care

Roughly half of Missouri respondents were confident they could find quality ratings for doctors (50%) and hospitals (53%). Nearly half (46%) of respondents reported trying to find quality information for a doctor in the past 12 months, while 42% sought quality information for a hospital.

Among those who tried to find quality information, the majority were successful. Eighty percent of those who tried to find doctor quality information were successful, while 77% of those who tried to find hospital quality information were successful.

Relationship Between Quality and Price

In light of well-documented, widespread variation in clinical quality and price,3 it is clear that consumers need both price and quality information to successfully identify providers and treatment options that are of “good value” (within a limited assortment of “shoppable” procedures). Researchers have established that failing to provide quality data alongside price information may result in consumers using price as a proxy for quality,4 despite little evidence of a relationship between the two.5

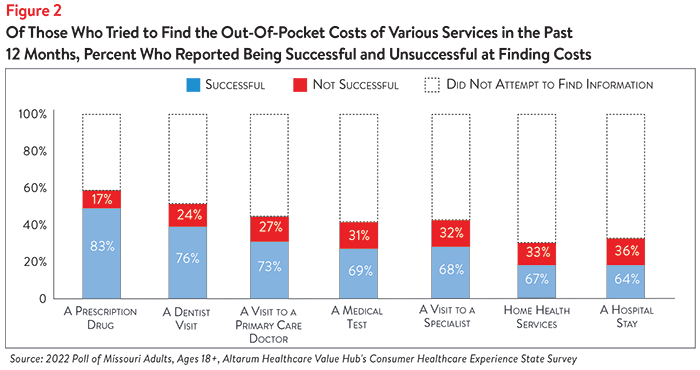

While 3 in 5 (61%) of Missouri respondents believe that higher quality healthcare usually comes at a higher cost, few believe that prices reliably signal the quality of care. Just 22% believe that a less expensive doctor is likely providing lower quality care (see Figure 3).

More than half (57%) believe that, if two healthcare providers had equal quality ratings, out-of-pocket costs would be a very or extremely important factor in deciding between the two professionals. Sixty-one percent believe that, if out-of-pocket costs were equal, quality ratings would be a very or extremely important factor in deciding between the two professionals.

Overall, 54% reported that quality information impacted their decision whether or not to see a particular doctor or go to a particular hospital in the last 12 months.

Support for “Fixes” Across Party Lines

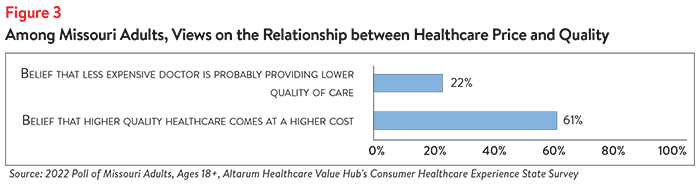

Far and away, Missouri respondents see the government as the key stakeholder that needs to act to address health system problems. When it comes to tackling costs, respondents endorsed a number of transparency-oriented strategies, indicating a need for insurers, drug companies and providers to work on consumers’ behalf.6 Specifically, the majority of respondents think that government should:

- 94%—Show what a fair price would be for specific procedures

- 92%—Require insurers to provide up-front cost estimates to consumers

- 92%—Require hospitals and doctors to provide up-front cost estimates to consumers

- 91%—Require drug companies to provide advanced notice of price increases and information to justify those increases

- 90%—Ensure patients can’t be charged out-of-network prices if they encounter an out-of-network provider through no fault of their own7

Strikingly, respondents strongly endorsed these approaches across party lines (see Table 1).

Discussion

Price transparency is instrumental to keeping consumers safe by allowing them to judge affordability and plan for the expense of needed healthcare services. It also enables state policymakers to address unwarranted price variation and, in some cases, can incentivize high-cost providers to lower their prices to align more closely with industry rates.

Despite its merits, price transparency is also inappropriately credited for its ability to make markets more efficient. Most notably, transparency tools have generally not been successful when it comes to incentivizing consumers to compare services and shop for the best price.8 This failure stems from tools that don’t contain the types of actionable information consumers need and from the fact that some consumers don’t view healthcare as a “shoppable” commodity. In fact, many healthcare services are not shoppable, such as those provided in emergency situations and settings that lack a selection of treatments/providers.9 Additionally, price may not the most important factor in healthcare decisions. For example, many patients defer to the courses of treatment their doctors recommend. Other reasons consumers discount price from their healthcare decisions include a preference for the perceived “best care,” regardless of expense; inexperience or discomfort with making trade-offs between health and money; and a lack of interest in or familiarity with costs borne by insurers and society as a whole.

Conclusion

Missouri respondents demonstrate that they are knowledgeable about the lack of relationship between the cost and quality of healthcare services, even if some believe that higher quality healthcare comes at a higher cost. Around three-fourths have sought out price information, and around half have sought out quality information. This presents challenges if people ultimately seek out care that is low cost, irrespective of quality.

While nearly half of respondents lack confidence in their ability to find healthcare price information, the majority of those who attempt to find it are successful, although success is lower for complex services like medical tests and hospital stays. A slightly greater share of respondents who sought quality information were successful than those who sought price information.

Respondents strongly endorsed a range of policy actions that elected officials could pursue, both transparency- and non-transparency-related. Policymakers should note, however, that the pursuit of transparency initiatives alone is unlikely to move the healthcare affordability needle. Efforts to improve transparency should be paired with other strategies that lower the unit prices of healthcare services, reduce the provision of low-value care and expand coverage options with adequate cost-sharing provisions.

Methodology

For the complete methodology, please see Missouri Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Worry about Affording Healthcare in the Future; Cite Unfair Prices Charged by Powerful Industry Stakeholders; Support Government Action across Party Lines.

Notes

1. For information on a broader range of healthcare affordability burdens and support for solutions, see: Missouri Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Worry About Affording Future Care; Cite Unfair Prices Charged by Powerful Industry Stakeholders; Support a Range of Government Solutions Across Party Lines, Healthcare Value Hub, Data Brief No. 121 (August 2022).

2. This survey was conducted after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ rule requiring hospitals to publicly display all standard charges for all items and services, as well as shoppable services, in a consumer-friendly format went into effect. While survey respondents may be reflecting on their experiences from before the rule went into effect, the well-documented low compliance from large hospitals indicates that the rule has yet to demonstrate the desired effect. See: Kurani, Nisha, et al., Early Results from Federal Price Transparency Rule Show Difficulty in Estimating the Cost of Care, Kaiser Family Foundation (April 9, 2021). See also: Henderson, Morgan, and Morgane C. Mouslim, “Low Compliance from Big Hospitals on CMS’s Hospital Price Transparency Rule,” Health Affairs Blog (March 16, 2021).

3. Cooper, Zack, et al., The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured, Health Care Pricing Project (May 2015). http://www.healthcarepricingproject.org/papers/paper-1

4. Hibbard, Judith H., et al., “An Experiment Shows That A Well-Designed Report On Costs And Quality Can Help Consumers Choose High-Value Health Care,” Health Affairs (March 2012).

5. Hussey, Peter, Samuel Wertheimer and Ateev Mehrotra, “The Association Between Health Care Quality and Cost: A Systematic Review,” Annals of Internal Medicine (Jan. 1, 2013).

6. Missouri respondents also endorse a range of strategies beyond the transparency approaches included here. For other strategies, please see: Missouri Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Worry About Affording Healthcare in the Future; Cite Unfair Prices Charged by Powerful Industry Stakeholders; Support a Range of Government Solutions Across Party Lines, Healthcare Value Hub, Data Brief No. 121 (August 2022).

7. This policy strategy has been implemented at the federal level through the 2020 No Surprises Act, but state governments may issue their own policies to bring state statute in line with the federal law. Importantly, unexpected medical bills resulting from ground ambulance services are not addressed by the No Surprises Act.

8. Revealing the Truth about Healthcare Price Transparency, Healthcare Value Hub, Research Brief No. 27 (June 2018).

9. Researchers at RAND and the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) have identified a limited set of healthcare services that are potentially shoppable in advance. See: Frost, Amanda, David Newman and Lynn Quincy, “Health Care Consumerism: Can the Tail Wag the Dog?” Health Affairs (March 2, 2016).