Oregon Residents Worried about High Drug Costs–Support a Range of Government Solutions

According to a survey of more than 900 Oregon adults, conducted from April 13, 2021, to April 29, 2021, residents are concerned about prescription drug costs and express a strong desire to enact solutions.

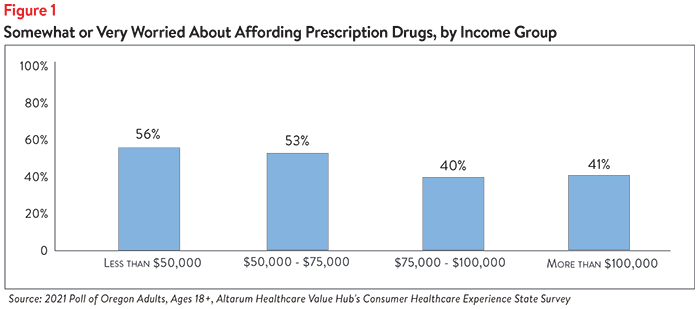

Almost half of all survey respondents (49%) reported being either “somewhat worried” or “very worried” about affording the cost of prescription drugs. Worry varied substantially by income group, with residents in households making less than $75,000 per year experiencing the most worry (see Figure 1). Residents in these income groups were much more worried than those in households making more. However, it is important to note that a large percentage of households making $75,000-$100,000 and more than $100,000 both experienced worry about affording prescription drugs.

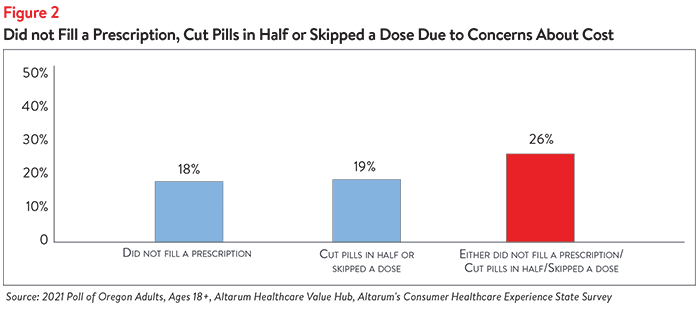

In addition to being worried about prescription drug affordability in the future, many Oregon residents experienced hardship in the prior 12 months due to the cost of prescription drugs. Indeed, cost concerns led 1 in 4 Oregon adults (26%) to not fill a prescription, cut pills in half or skip a dose of medicine (see Figure 2).

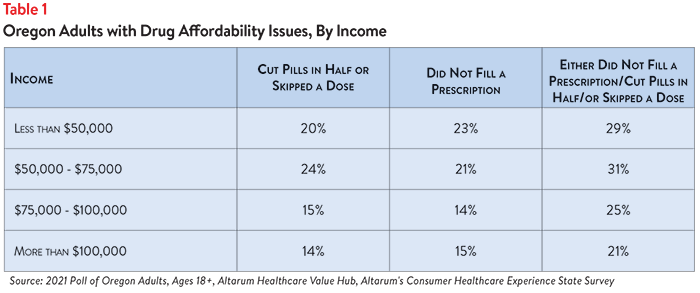

These hardships disproportionately impact people in lower income households. As Table 1 shows, people in households earning less than $50,0001 per year are more likely to have rationed their prescription medicines (by not filling a prescription, cutting pills in half or skipping a dose of medicine) than people in households making more than $100,000 per year. These hardships are alarmingly prevalent in middle income households, as well.

When given more than 20 options, the option cited most frequently as being a “major reason” for high healthcare costs was “drug companies charging too much money:”

- 74%—Drug companies charging too much money

- 68%—Insurance companies charging too much money

- 66%—Hospitals charging too much money

In light of these prescription drug cost concerns—as well as concerns about high healthcare costs generally2—it is not surprising that Oregon adults are extremely dissatisfied with the health system:

- Just 26% agreed or strongly agreed that “we have a great healthcare system in the U.S.,”

- While 71% agreed or strongly agreed that “the system needs to change.”

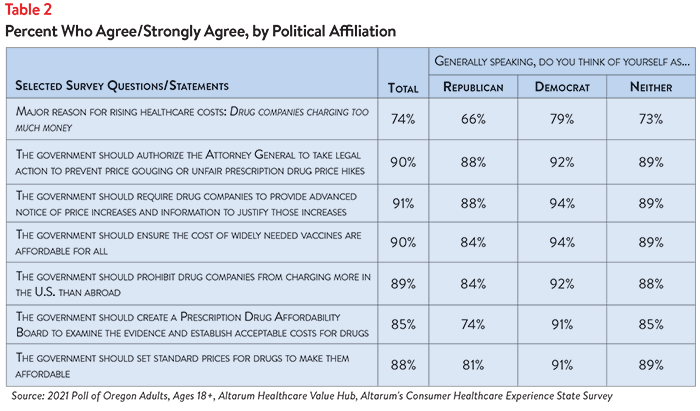

When it comes to tackling high drug costs, Oregon adults endorsed a number of strategies:

- 91%—Require drug companies to provide advanced notice of price increases and information to justify those increases3

- 90%—Authorize the Attorney General to take legal action to prevent price gouging or unfair prescription drug price hikes

- 90%—Ensure the cost of widely needed vaccines are affordable for all

- 89%—Prohibit drug companies from charging more in the U.S. than abroad

- 88%—Set standard prices for drugs to make them affordable

- 85%—Create a Prescription Drug Affordability Board to examine the evidence and establish acceptable costs for drugs

There is remarkably high support for government action on drug costs regardless of the respondents’ political affiliation (see Table 2).

While Oregon residents are united in calling for the government to address high drug costs, they also see a role for themselves:

- 76% would switch from a brand name to an equivalent generic drug if given a chance

- 56% have tried to find out the cost of a drug beforehand

The high burden of healthcare and prescription drug affordability, along with high levels of support for change, suggest that elected leaders and other stakeholders need to make addressing this consumer burden a top priority. Moreover, the current COVID crisis is leading state residents to take a hard look at how well health and public health systems are working for them, with strong support for a wide variety of actions. Annual surveys can help assess whether or not progress is being made.

Notes

1. Median household income in Oregon was $62,818 (2015-2019). U.S. Census, Quick Facts. Retrieved from: U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Oregon

2. For more detailed information about healthcare affordability burdens facing Oregon residents, please see Healthcare Value Hub, Oregon Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; COVID Fears Add to Support for a Range of Government Solutions Across Party Lines, Data Brief No. 91.

3. In 2019, Oregon passed the Prescription Drug Price Transparency Act, which, among other things, requires drug manufacturers to report price increases to the Department of Consumer and Business Services at least 60 days before the increase is set to take place. For more information, see: Prescription Drug Price Transparency, Oregon Division of Financial Regulation (Accessed June 3, 2021). https://dfr.oregon.gov/drugtransparency/Pages/index.aspx

Methodology

Altarum’s Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) is designed to elicit respondents’ unbiased views on a wide range of health system issues, including confidence using the health system, financial burden and views on fixes that might be needed.

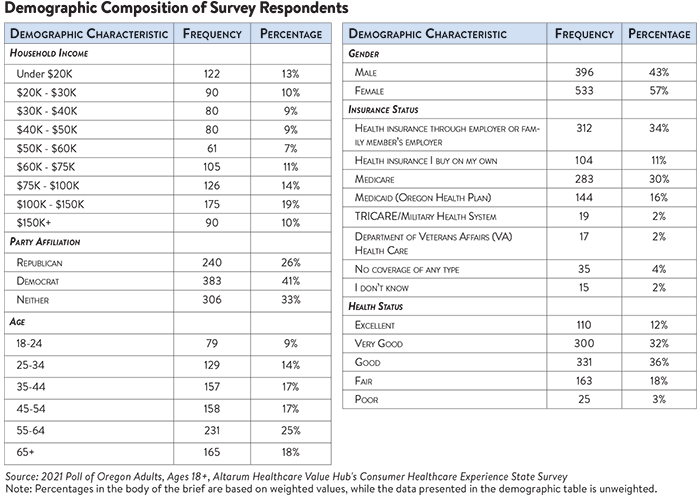

The survey used a web panel from Dynata with a demographically balanced sample of approximately 1,000 respondents who live in Oregon. The survey was conducted in English or Spanish and restricted to adults ages 18 and older. Respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median time were excluded from the final sample, leaving 929 cases for analysis. After those exclusions, the demographic composition of respondents was as follows, although not all demographic information has complete response rates: