Colorado Residents Concerned About Healthcare Quality; Unsure How to Find Answers

A new survey of more than 970 Colorado adults conducted from Dec. 20, 2018 to Jan. 2, 2019, found that:

- More than half (66%) of adults are worried about getting low-quality healthcare

- Only a little over one-third (35%) used quality information to decide on a particular doctor or hospital

What Does Healthcare Quality Mean

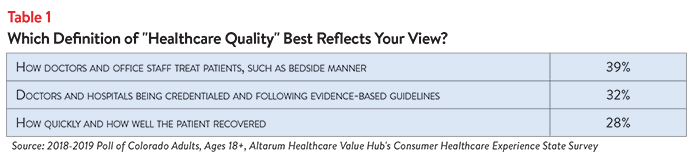

National survey data and qualitative research have signaled that patients often have a different view of what healthcare quality means compared to researchers or doctors.1 Findings from the Colorado survey align well with this national data.

Out of three choices, Colorado consumers most commonly selected this definition for healthcare quality: “how doctors and office staff treat patients, such as bedside manner.” However, the other two definitions tested were selected at only a modestly lower frequency (see Table 1).

In light of the importance of bedside manner to Coloradans, good news from the survey is that about three-fourths (76%) of adults in Colorado indicated they almost always or always feel that their doctors treat them with respect.

Confidence in Finding Quality Information is Low

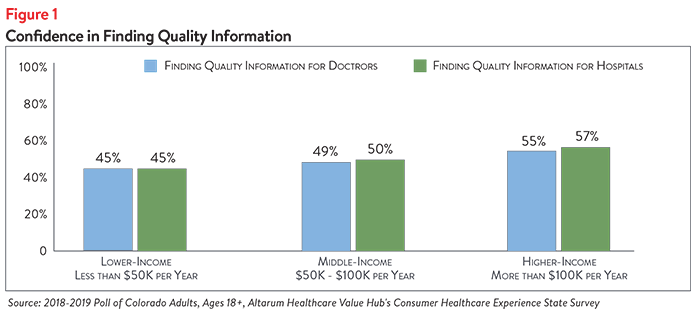

When it comes to selecting quality providers, adults in Colorado are not confident in their ability to find quality ratings for doctors or hospitals. Only about 50% of respondents reported they were “very” or “extremely confident” they could perform these tasks.2

By way of comparison, respondents were far more confident they could perform health system tasks like “Follow Medical Directions from a provider” (81% “Very” or “Extremely Confident”) or “Fill a prescription” (78% “Very” or “Extremely Confident”).

Compared to others, lower income adults had the least confidence in finding quality information for doctors and hospitals but, more importantly, there were low degrees of confidence at all income levels (see Figure 1).

Does Higher Quality Come at a Higher Cost?

In light of well-documented, widespread variation in clinical quality and price,3 it is clear that consumers need both price and quality data if they are to successfully identify providers and treatment options that are of “good value.” Researchers have established that if comparison measures fail to provide quality data alongside price information, consumers may use high price as a proxy for high quality,4 despite the fact that there is little relationship between the quality and price of a medical service.5 This survey investigates Colorado respondents’ views on the relationship between quality and price.

More than half of Colorado adults (61%) believe that higher quality health care usually comes at a higher cost, yet, very few believe that price reliably signals the quality of care. In other words, they believe the quality care is likely to be high price but not all high price care is quality care. Just 25% believe that a less expensive doctor is likely providing lower-quality care.

Just over half of respondents (55%) indicated that if out-of-pocket costs were about equal, quality ratings would be very or extremely important. Similarly, just over half (53%) of survey respondents also indicated that if quality ratings were about equal, out-of-pocket costs would be very or extremely important.

These findings suggest that quality information is an important factor in health care decisions.

Healthcare System Fixes

Fifty-two percent of respondents rated the overall quality of the healthcare system as “excellent” or “good,” while far fewer gave the health system a “good” or “excellent” rating for fairness (35%) or affordability (20%).

When it comes to addressing health system problems, 4 in 5 (84%) of Colorado adults supported having the government establish an independent entity to rate doctor and hospital quality, such as patient outcomes and bedside manner. Importantly, respondents also gave a large number of other solutions high marks.6 Remarkably, these solutions received broad support across party lines.

While Colorado residents are united in strongly calling for government action setting up an independent entity to assess quality,7 they also see a role for themselves—albeit a far more modest one. Out of 10 possible personal actions they could take to address healthcare system problems, the action of “doing more to compare cost and quality before getting services” ranked 5th behind:

- (68%)—taking better care of their personal health

- (37%)—writing to or calling my FEDERAL representative asking them to take action on high healthcare prices and lack of affordable coverage options.

- (36%)—writing to or calling my STATE representative asking them to take action on high healthcare prices and lack of affordable coverage options

- (35%)—researching treatments myself before going to the doctor

Bottom line: while respondents indicate a willingness to use healthcare quality data, they don’t see personal actions as powerful as government actions in terms of fixing the healthcare marketplace.

Summary

Varying stakeholder views about what is meant by “healthcare quality” suggest that advocates and policymakers have to tread carefully when it comes to providing quality information to keep consumers safe in the healthcare marketplace. Given the still-early-stages of healthcare quality transparency tools, it is perhaps not surprising that adults in Colorado report that quality information can be difficult to access and difficult to interpret.

Across party lines, respondents issued a strong call for an independent entity to rate doctor and hospital quality, such as patient outcomes and bedside manner.

As detailed in a companion report,8 respondents also called for strong legislative action to address the high burden of healthcare affordability. As legislators respond to this call for action, addressing quality variation and short-comings in quality transparency tools are good companion approaches to ensure that healthcare quality is not undermined as Colorado’s healthcare system is transformed.

Notes

1. For example, see: The Patient as Consumer and the Measurement of Bedside Manner (March 2017); First-Of-Its-Kind Survey Reveals Significant Disconnects In How Three Key Stakeholders—Patients, Physicians, Employers—Perceive The Health Care Experience (November 2017); "U.S. Doctors are Judged More on Bedside Manner than Effectiveness of Care, Survey Finds," BMJ (July 2014); and 2017 Consumer Health Care Priorities Study: What Patients and Doctors Want from the Health Care System (November 2017)

2. A dearth of tools may contribute to Coloradans’ inability to find quality information. In a national survey of state and national healthcare price and quality tools, only the “Hospital” section had a Colorado-specific tool to compare hospitals. The “Physician” section only has national databases to search for providers. See: http://www.healthcaretransparency.org/

3. Cooper, Zach, et al., The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured, Health Care Pricing Project (May 7, 2018). http://www.healthcarepricingproject.org/papers/paper-1

4. A 2012 study involving 1,421 consumers found that significant numbers of respondents—though not a majority—viewed higher cost as a proxy for higher quality. This was true even among those with high-deductible health plans that would expose them to a higher share of costs. But when the cost and quality information was reported side by side in an easy-to-interpret format, more respondents made high-value choices. J. H. Hibbard, J. Greene, S. Sofaer et al., “An Experiment Shows That a Well-Designed Report on Costs and Quality Can Help Consumers Choose High-Value Health Care,” Health Affairs (March 2012).

5. Hussey, P., Wertheimer, S., and Mehrotra, A. “The Association Between Health Care Quality and Cost: A Systematic Review,” Annals of Internal Medicine (2013).

6. For other strategies receiving high levels of support, see: Healthcare Value Hub, Colorado Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Support a Range of Government Solutions Across Party Lines, Data Brief No. 30 (February 2019). http://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/Colorado-2019-healthcare-survey/

7. At the time of this report, Colorado Governor Polis has called for a new office called the Office of Saving People Money in Health Care.

8. See: Healthcare Value Hub, Colorado Residents Struggle to Afford High Healthcare Costs; Support a Range of Government Solutions Across Party Lines, Data Brief No. 30 (February 2019). http://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/Colorado-2019-healthcare-survey/

Methodology

Altarum’s Consumer Healthcare Experience State Survey (CHESS) is designed to elicit respondents’ unbiased views on a wide range of health system issues, including confidence using the health system, financial burden, and views on fixes that might be needed.

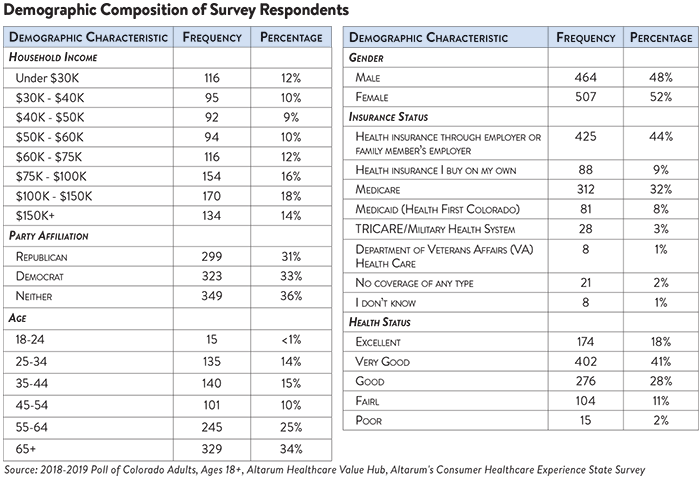

The survey used a web panel from SSI Research Now containing a demographically balanced sample of approximately 1,000 respondents who live in Colorado. The survey was conducted only in English and restricted to adults ages 18 and older. Respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median time were excluded from the final sample, leaving 971 cases for analysis with sample balancing occurring in age, gender and income to be demographically representative of Colorado. After those exclusions, the demographic composition of respondents is as follows.